When Rhodri Morgan, the former First Minister of Wales, was given a public, humanist funeral at the Welsh Parliament in 2017, the event was heralded as a landmark, a symbol of a modern, secular Wales. Indeed, over the past twenty years, Wales has established itself as the most secularised part of Britain. According to the 2021 Census, almost half the population has no religion. In the former mining valleys of the south, local rates of irreligion even exceed sixty percent. On the surface, this might appear to be a contemporary phenomenon, one linked to deindustrialisation and its longer-term social consequences. After all, the recorded rate of irreligion was under twenty percent of the Welsh population as recently as 2001. But would religious observance have continued in the shadow of the mine? As a historian of modern Wales, I am not convinced.

In retrospect, earlier census data evidently captured nominal rather than actual identification with religion. Chapel attendance has been in decline for generations and even brief comparisons between historic maps and contemporary streetscapes reveal a steady rate of building demolition. I want to suggest that the Welsh did not turn their backs on organised religion in the wake of deindustrialisation. Rather, a secular mentality emerged in Wales more than a century ago during the zenith of the steam coal industry.

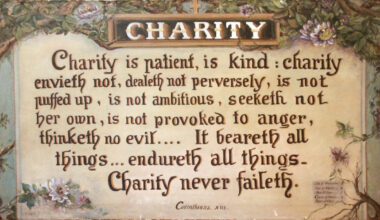

This was a period when new ways of thinking and new political movements combined with economic prosperity and large-scale immigration to create the conditions of modernity. Out of this crucible of change came social democracy on the one hand and on the other a secular society, one in which the authority of the nonconformist chapel rapidly declined. ‘It changed all of a sudden,’ the Rhondda novelist Gwyn Thomas later observed, ‘nobody would ever listen to them [the chapel preachers] again with a grain of belief.’

What follows considers two key themes: the intellectual influences which led individuals towards a secular mentality and the organisational geography of the secular movement in the valleys of southern Wales in its heyday. By way of conclusion, I examine the longer-term legacy of this history and its influence on the social democratic politics which have shaped Wales since the 1920s.

Intellectual influences

George Daggar was the Labour member of parliament for Abertillery (now in Blaenau Gwent) from 1929 until his death at the age of seventy in 1950. Whenever he was asked about his faith, he responded by saying that he was agnostic. He probably had in mind the Edwardian sense of ‘professing ignorance, especially in religion.’ The response was sufficient to preserve his image as a popular representative, since he privileged neither the religious nor the irreligious. But it was not an accurate description. Daggar’s lack of religious faith went even further. Indeed, he conducted and attended funerals of atheists and filled his bookshelves with secularist and humanist material.

But where had these secular convictions come from? One clue lies in Daggar’s surviving book collection, now housed at the South Wales Miners’ Library in Swansea. At the age of seventeen or eighteen, he bought a copy of the debate between W. T. Lee and Freethinker founder George William Foote, which was published in 1896 as Theism or Atheism: Which Is More Reasonable? Foote’s argument in favour of atheism awoke the young man to an intellectual world outside of the chapel, a secular alternative to the Liberal-Nonconformity then dominant in his hometown of Abertillery. Compelled by his discovery, he began to explore these questions further. This exploration would lead him to reject religion. By the time Daggar bought his copy of Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian on its release in 1927, his secular mentality was firmly established.

Daggar’s teenage encounter with these strands of thought was by no means unusual: there were active members of the National Secular Society in Blaenavon, a few miles away in a neighbouring valley, by 1895. Although Daggar has sometimes been described as unique amongst the Welsh parliamentary cohort of the 1930s and 1940s for his lack of religious faith, this too is inaccurate. His colleagues, including Aneurin Bevan and Ness Edwards, the Abertillery-born MP for Caerphilly, travelled much the same path; so did Rhondda’s Iorrie Thomas. In fact, as Leo Abse was later to describe in his book Private Member (1973), a memoir based on his own parliamentary career as MP for Pontypool, these men had an ‘extravagant hatred of the chapel, against whose narrow restrictions they had rebelled in their adolescence.’

Geographies of organisation

It is not coincidental that Ness Edwards and George Daggar should have developed their secular mentality in Abertillery: this town was one of the centres of secularism in the Welsh valleys in the early twentieth century. The other focal points were Blackwood, New Tredegar, Merthyr Tydfil, Aberdare, Mountain Ash, Pontypridd, Rhondda, Neath, Ogmore Vale, Cardiff and Swansea. Remarkably, this is almost the same geography as that identified in the 2021 Census. The three most secular local authorities being recorded as Blaenau Gwent (covering Abertillery), Caerphilly (covering Blackwood and New Tredegar), and Rhondda Cynon Taf (covering Aberdare, Mountain Ash, Pontypridd, and Rhondda).

In the 1890s, my own hometown of Pontypridd was the most important. The local branch, described in the Freethinker as being made up of ‘nearly all working men,’ was able to attract national speakers, including Chapman Cohen and G. W. Foote, to lecture and debate, and members held social events like a commemorative party to mark Charles Bradlaugh’s birthday. Their headquarters was an unassuming terraced house in a multicultural district of the town, largely populated by workers employed by the nearby Brown Lenox Chainworks. Amongst the neighbours was the grandfather of the comedian Sacha Baron Cohen.

The man who was to the lead the Pontypridd branch of the National Secular Society for much of its existence was a miner called Sam Holman. A migrant from Frome in Somerset who was employed at the Cymmer Colliery in Porth in the Rhondda, Holman was in his early thirties when the Pontypridd NSS branch was formed in 1897. As the commemorative party suggests, he and his fellow secularists took their initial intellectual cues from Bradlaugh and then from visiting lecturers.

As the local secular movement grew larger and more sophisticated, other influences were to become apparent. Wil Jon Edwards, for example, who helped to form the Aberdare branch of the NSS in 1907 and became its secretary, subscribed to the Freethinker. His 1956 memoir, From The Valley I Came, written when he was in his late sixties, adds further detail. ‘The rot set in,’ he writes of his abandonment of the chapel, ‘when I got from the library a book called English Social Reformers [by Henry de Beltgens Gibbins].’ Edwards soon gave up attending chapel in favour of reading books, filling his mind with fresh ideas. This was to lead to tensions at home and pressure to return to the fold, which Edwards resisted. He was asked why he consorted with atheists, but gave no reply. ‘I did not answer,’ he reflected, ‘because I would have had to [explain] that I would never go back.’

Legacies

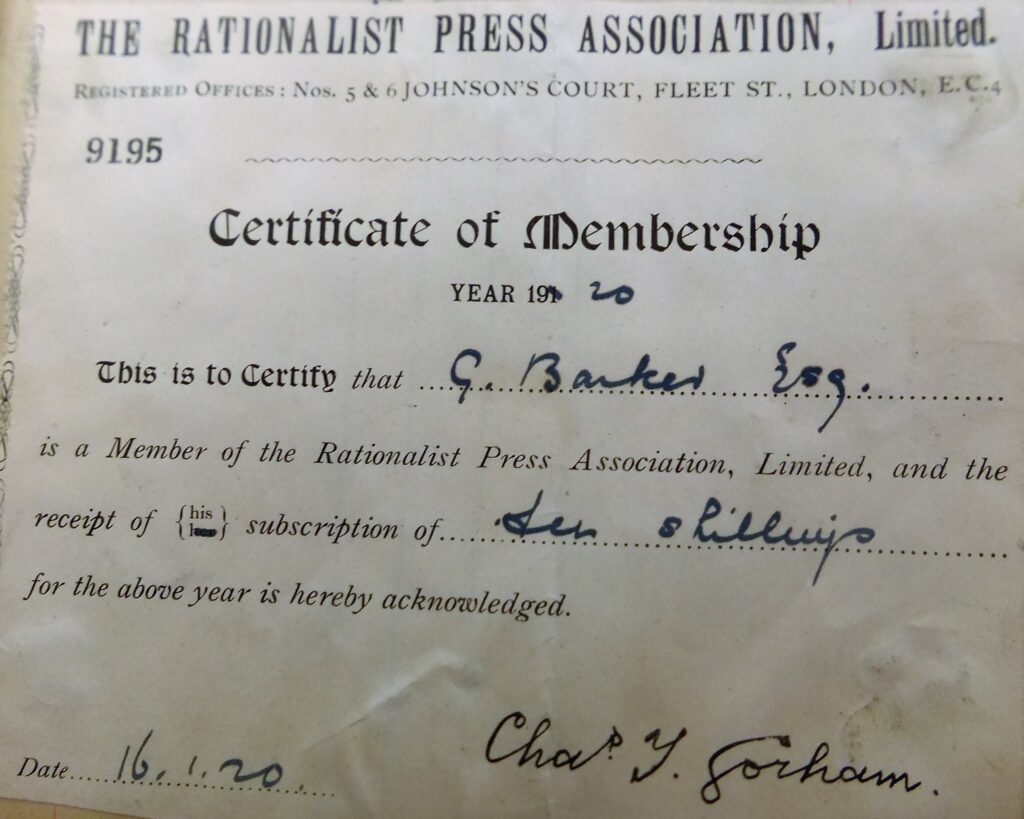

After the First World War, the flourish of organised secular activity in the valleys of southern Wales declined. But the mentality which had emerged did not disappear. It found expression, instead, in the social democratic politics of the interwar years. This is apparent in the scrapbooks compiled by George Barker, now housed in the archives at Cardiff University. Barker was elected to parliament in 1920 as the Labour MP for Abertillery, serving until his retirement in 1929. Already in his sixties, with an active schedule of lectures and platform appearances to maintain, he nurtured his secular outlook through a variety of subscriptions and memberships including to the The Positivist Review and the Rationalist Press Association. Although Barker’s personal library is not in the archives, it is nevertheless clear from receipts and postal orders pasted into the scrapbooks that he made regular book purchases from the Rationalist Press Association; these were to shape his outlook in his later years. He died in 1936.

Others went even further, becoming outspoken opponents of organised religion. Will Paynter, who was to serve as General Secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers in the 1960s, was one who, in his words, ‘took a stand.’ He left the chapel in as dramatic a way as possible, paving the way for his absorption in Marxism and entry into the Communist Party. Aware of Paynter’s wavering religious faith, the local minister had turned up at the young man’s house to pray for his salvation and to encourage a return. But Paynter was having none of it. ‘I yanked him to his feet,’ Paynter later recalled, before telling the minister that ‘if he couldn’t convince me on the basis of logical argument, he wasn’t going to do it by emotional pressures.’ The minister was then ejected. Nowadays, of course, little force is required.

Sadly, historians have little remarked on the secular influences present in Welsh social democracy. The chapel, long since taken over by pigeons and weeds in real life, continues to exercise its historic influence in intellectual circles. But if we are to fully understand the death of Christian Britain, then we should think again about the secular mentality of the South Wales Valleys.

Enjoy this article? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on freethought.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate