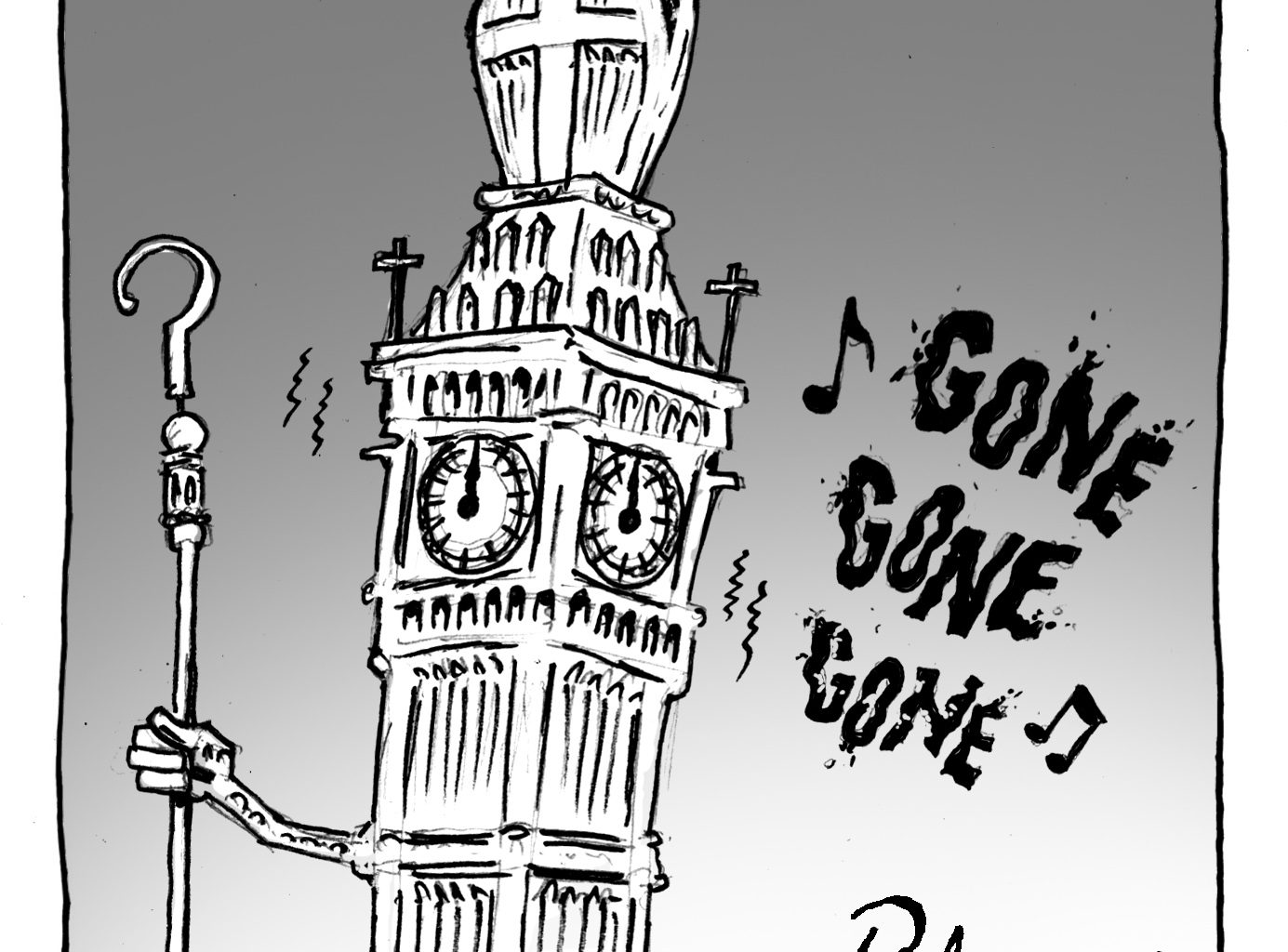

Through nearly five hundred years of constitutional change, the Church of England has clung on to its entitlement to bishops in the House of Lords. Never mind that no other country in the modern world, except for Iran, has representatives in its Parliament who are there solely by virtue of being religious leaders. Never mind the anachronism of a liberal democracy whose Head of State is anointed by an archbishop, and whose present incumbent swore to ‘maintain the Laws of God and the true profession of the Gospel’, as well as to ‘preserve unto the Bishops and Clergy of England…all such rights and privileges, as by law do or shall appertain to them’.

And never mind the Heir Apparent’s even more eccentric idea of becoming ‘Defender of Faith’ (which, according to his official website, he has now ditched) thereby encompassing all religions whatsoever practised in Britain, but excluding the non-religious majority of his subjects, particularly the young. (The Freethinker respectfully suggests that a more inclusive title would be Defender of All Faiths and None.*)

The number of Lords Spiritual is limited to a maximum of 26 by statute. There are at present 24, five women and 19 men. Women bishops were not approved by the General Synod of the Church of England until 2014; weirdly, those now in Parliament receive the title of ‘Lord Bishop’, as though no one had noticed they were female.

Despite being a small proportion in a House of ‘about 800’, the bishops’ status is privileged by procedure. They sit on the government side of the House, on the two front benches nearest the throne. Every day that the Lords are in session, one of them leads prayers before the official proceedings can begin. When a bishop stands up to speak or ask a question, according to Liberal Democrat peer Dick Taverne, they are ‘entitled to precedence’. The Lords Spiritual must retire at 70, although former Archbishops of Canterbury and York customarily receive a life peerage, and so continue to sit in the House after retirement.

In the last two decades, the bishops’ record in the legislative process has been mixed. They tend to participate less than other peers: according to a House of Lords Library Briefing, their attendance in the 2005–06 and 2016–17 sessions averaged 18 per cent, compared with 58.5 per cent for the House as a whole.

The bishops are not affiliated to a particular party, and do not always vote as a bloc. Usually, they turn up in larger numbers for issues relating to religion or education. For instance, nine voted against the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Bill in 2013, while five abstained and the rest stayed away.

The most controversial debate in which the Lords Spiritual have been involved recently, together with other religiously affiliated peers, has been the debate on Baroness Meacher’s Bill, which took place on 22nd October 2021. The Assisted Dying Bill, as it is formally known, would legalise medically assisted suicide for terminally ill people who are ‘reasonably expected to die within six months’.

During the debate, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, and the bishops of Durham, Carlisle and Chichester, spoke out in opposition to the Bill. Welby declared, on behalf of the Bishops’ bench, that there was ‘unanimity…that our current law does not need to be changed.’ John Sentamu, the former Archbishop of York and now a life peer, also opposed the Bill. It did, however, receive support from other religious peers outside the Lords Spiritual, including the former archbishop George Carey, Ruth Davidson (Church of Scotland), Augustine O’Donnell (Catholic), and Lord Leigh (a self-described ‘progressive Jew’).

Reading the Hansard report, it is striking how many times religious beliefs were invoked, particularly in opposition to the Bill. Lord Eames, former Primate of All Ireland, described how he had often ‘prayed that a person’s suffering would cease—that somehow, in my faith, the Almighty would receive them out of their pain.’ Lord Davies of Gower, a Conservative, admitted that ‘my Christian beliefs play a big part in this.’ Lord Sheikh asserted that ‘human life is sacred…As a Muslim, I am totally opposed to this Bill.’ ‘We have to accept the will of almighty God,’ said Lord Suri, a Sikh peer. ‘The holy scripture of Sikhism says that whosoever has come into this world has to go on their allotted day.’ Another Sikh peer, Lord Singh, invoked religious authority in his claim that ‘assisting in the killing of our fellow human beings has been condemned by leaders of all our major faiths.’

At times, the debate strayed into the otherworldly. Lord Cormack, a Christian, criticised the Bill’s failure to ‘acknowledge the fact that many of us believe in the afterlife’. The ‘judgment’ after death was also invoked by Lord McCrea, a retired Presbyterian minister. ‘The man God, Jesus Christ,’ said the Bishop of Chichester, ‘experienced the evil and suffering of the cross in order that we….might find hope and the recovery of life in heaven.’ The award for the most mystical contribution, however, goes to Lord Pearson, former leader of UKIP, who described going through a ‘near-death experience’ during which he seemed to hear a ‘wonderful voice’ and was ‘told that all this, the eternal force of good, was losing to its opposite, the eternal force of evil’.

The closing speech was given by Robert Winston, the eminent scientist, Labour peer, and presenter of the BBC documentary The Story of God. Winston noted that, if the Bill should proceed to committee stage, ‘the Bishops’ Bench is extremely important in this.’ Although, he said, he was a Jew, not a Christian, nevertheless, ‘the influence the bishops have on the moral compass of this debate is extremely important.’ He stressed that the debate ‘is not an argument about religion; religion is irrelevant. The debate is about how we understand what our ethical standards should be and how we maintain the ethics of our society.’

These remarks are telling. If religion was not relevant, then why should the ethical views of the bishops, rather than of anyone else, play such a key role? In fact, the Hansard report reveals that, for several peers, religion was clearly of central relevance – even if they were a minority in a debate that lasted eight hours. For the ‘unbeliever’ Lord Lipsey, a Labour peer, religion was ‘the Banquo at the feast’, hovering in the background even more than it was expressly articulated.

Somehow, the Lords Spiritual are considered to have a special authority both to speak about death and to influence legislation which the government has already said, in response to a petition, is an ‘issue of conscience’. The laws on assisted dying, however, affect everyone, not just those with religious beliefs; and the population as a whole seems to be much more supportive of reform than the bishops. The debate on Meacher’s Bill thus provides a clear demonstration of the flaws in allowing bishops in Parliament: first, they are perceived to have a particular authority on ‘moral’ issues, and second, their presence there seems to encourage other peers to appeal to religious beliefs in a matter of secular legislation.

Whether Meacher’s Bill will progress further before the end of the Parliamentary session this summer seems increasingly unlikely: various members of the Lords have proposed 212 amendments that would be a marathon to get through. The Conservative peer, Lord Forsyth, recently tried to force the government to consider assisted dying via an amendment to the Health and Care Bill. During the debate on the Bill, he withdrew his amendment. However, he has not yet given up. As he tells me via email, ‘I intend to put it to a vote unless the Government gives me an undertaking to provide time for a future private members bill.’ It will be interesting to see how the bishops respond.

On occasion, the bishops also turn up to vote on legislation which seems to have little to do with Christianity. For instance, nine bishops helped to defeat a clause in the government’s Internal Market Bill 2020, which would have allowed ‘ministers to disapply the Northern Ireland protocol with the European Union,’ while eight voted against a clause which would have allowed the government to ‘renege on the Withdrawal Agreement’, according to the Church Times. In such clearly secular issues, the case for the involvement of religious representatives is even weaker.

The Church of England is ‘remote from reality’, Taverne told me in an interview. On 28th January 2020, he introduced a private member’s bill to remove the bishops’ entitlement to membership of the Lords, a topic on which he has long been vocal. Conventionally, the first reading of a bill is a formality. But this time, he says, there was a ‘stir of protest from the Conservative benches’ (this can be heard in the video). ‘It was a very curious occasion,’ he says; afterwards, ‘Lots of people came up to me and said, “Good bill!”’ But the pandemic struck before the Bill could move to its second reading; as a result, according to the UK Parliament website, it will ‘make no further progress.’ Unfortunately, says Stephen Evans of the National Secular Society, there are no other peers who are willing to ‘stick their heads above the parapet’ on this issue.

Despite its continuing participation in politics, there are signs that even within the Church of England, there are suspicions that the Bishops’ Bench is untenable, at least in its present form. In February this year, a confidential document about proposed reforms to the system of bishops was leaked to the Church Times. The document, entitled A consultation document: Bishops and their ministry fit for a new context, was co-authored by Maggie Swinson, Mark Sheard and Stephen Conway, who is on the Bishops’ Bench. It has since been made publicly available. Among other proposals, the authors, on the basis of a ‘listening exercise with current Lords Spiritual (and indeed with other diocesan bishops)’, anticipated that ‘reform of the House of Lords is inevitable at some stage.’ If the Church wanted to control the direction of this reform, the authors suggested, then this would need to involve ‘reduction in number of Lords Spiritual and the attachment of those roles to specific sees rather than by rotational allocation.’

It is unclear how far this analysis is shared by all senior members of the C of E. (The Church did not respond to a request for comment.) However, it does seem to suggest a certain desperation to cling onto political power, however minimal, rather than simply to give it up gracefully.

Some supporters of the bishops have been toying with another idea: to swell the numbers of the faithful in the Lords to include the diversely faithful. In 2018, Lord Bourne of Aberystwyth, the Conservative Minister for Faith under Theresa May (herself an avowed Anglican), ‘backed calls for leaders of other faiths to be added as official lords spiritual’ in the interests of ‘broader representation’, according to The Times.

But just which religions would be allowed in under such proposals? If Parliament intended to be as inclusive as some organisations, such as the Police Chaplaincy, it might have to feature representatives of Subud, Zoroastrianism and Bahá’i, as well as of atheism (strangely listed by the Chaplaincy under ‘Faith at a Glance’). Currently, scientology and druidism have been recognised, but Pastafarianism, in all likelihood, would not be. And yet, as worshippers of the Flying Spaghetti Monster would say, their creed is no more incredible than anyone else’s.

As far as Britain’s non-religious majority are concerned, the argument for group representation does not apply easily to them. Some might wish to be represented in Parliament by an organisation like Humanists UK, but many others would have little common ground with one another, ethical or otherwise, beyond the bare fact of not being religious. A similar point might be made about people who were religious in some sense but unaffiliated to a particular organisation or creed.

The argument can be made that some religious beliefs necessitate, at least in some circumstances, support for a particular political stance or course of action. However, there is a difference between advocating a policy in Parliament because of your religious beliefs, and being automatically entitled to sit in Parliament because of those beliefs, or because of your affiliation to a group that promotes them.

In general, the idea that political representation should require the individual to join an organisation defined by certain beliefs and practices, rather than simply making a decision on election day among a range of choices based on whatever considerations they think appropriate, is highly problematic. It is like saying that, to vote Labour, you must be a member of the Labour party; and if you are, then you cannot vote Conservative.

All of which suggests that there are serious flaws in the ‘faith leader’ model of political representation. The secularist position, in contrast, is that religion is a private matter. Political debate, which is a matter of public concern to everyone, must be conducted in terms of our common world and through arguments and terms of reference available to everyone. It is unjust for representatives of speculative belief systems to be given the moral and political standing to impose their views on others.

As outlined in a recent webinar from the UCL Constitution Unit, the House of Lords is in need of a multitude of reforms – but lack of agreement continues to hinder progress. Clearly, there are many other problems with the Lords, such as the continued space for 92 hereditary peers. But if Britain as a country wants a political system in which religious doctrines are not invoked in secular lawmaking, abolishing the bishops would be a good place to start.

*Omnium Fiderum Defensor Nulliusque

Update: Should the House of Lords have allocated seats for ‘faith leaders’? Add your vote to our Twitter poll.

Enjoy this article? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on freethought.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate