Nigeria’s secularism is faltering. Sadly, it holds little hope for Africa’s largest democracy, especially for its minority (ir)religious and belief groups. Section 10 of the nation’s 1999 constitution guarantees the separation of church (mosques, shrines, temples) and state, stipulating that ‘the Government of the Federation or of a State shall not adopt any religion as State Religion.’ But Nigeria’s secular character has so far been a paper tiger, due to the intense and pervasive mixing of faith and politics at all levels. In everyday governance and policymaking, the influence of religion is overwhelming.

The concept of ‘secularism’ is not mentioned in the constitution. This omission was a deliberate compromise to appease the Islamic establishment, which detests the idea of secularism and has been persistently antagonistic towards the notion of Nigeria as a secular state. This antagonism has increasingly polarised the country politically, because the idea of a secular state is distrusted and misunderstood as meaning an atheist state or a state which is configured to erode the influence and authority of religions.

With hindsight, the omission of secularism from the constitution was an early indication of what lay ahead: a battle for religious supremacy, a superimposition of religion, and a contest of religious politics. Nigeria after independence has been characterised by a fierce struggle by the two main religions, Islam and Christianity, to control and dominate the country’s political and social organisations. Internationally, Christian Nigeria has been backed by the Christian West, and Islamic Nigeria buoyed by the Islamic East. These two foreign faiths were introduced by Westerners and their Arab counterparts, who for centuries used to enslave or colonise Africans. For both Westerners and Arabs, imposing their faith on their African subjects formed a part of their imperialist agenda.

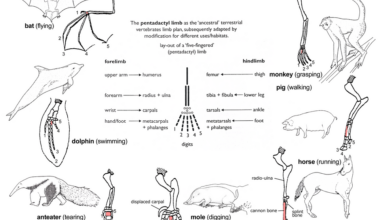

Western missionaries and Arab or north African jihadists treated traditional beliefs and institutions with contempt, designating other faiths, including local customs and practices, as fetishistic, idolatrous, abhorrent and primitive. After centuries of deploying physical and structural violence against traditional religions, Christianity and Islam have become the dominant faiths, and their privileges well established. Centuries of Christian and Islamic indoctrination have turned Nigeria into a ‘chrislamic’ stronghold: out of a population of around 218 million and counting, roughly half are Muslim and half are Christian (the precise numbers are uncertain and subject to constant fluctuation). Powerful Christian and Muslim authorities perpetuate a tradition of sociopolitical contempt towards other religious and non-religious traditions.

Non-believers are some of those most affected by this religious power game. This category includes Nigerians who identify as atheists, agnostics, humanists, freethinkers, sceptics, rationalists, or as religion-free individuals. Until recently those of no religion in Nigeria, who probably constitute about one per cent of the population, were largely invisible. This low number can be explained by the stigma attached to the open and public profession of atheism and irreligiosity, and to a deliberate policy of the suppression of irreligiosity. In general, the religious politics that prevails in Nigeria stifles the rights and liberties of unbelievers. In particular, the religious establishment continues to misrepresent the country’s (ir)religious demographics. For instance, there will be no question about religious affiliation in Nigeria’s 2023 census. So the 2023 census would not highlight the religious or irreligious demographics and the shifts that might have taken place since the last census.

Meanwhile individuals who identify as non-theists, or agnostics, or non-believers in the faith of Christianity and Islam, run the risk of suffering systemic discrimination, exclusion and persecution. As the case of Nigerian humanist Mubarak Bala has demonstrated, those who openly declare their lack of religious belief or dare to question the religious establishment risk being attacked, imprisoned or killed.

The imprisonment of Bala was a huge blow to secularism in Nigeria. It was part of a wider move by the religious and state authorities to clamp down and suppress irreligious expressions and manifestations. Bala’s case is an eloquent testimony to the systematic oppression of non-religious people. Nigerian Muslims are allowed to make statements that disparage non-believers, and to criticise unbelief as a part of their profession of faith: they may exercise their rights to freedom of religion or belief and freedom of expression. Unfortunately, in parts of Nigeria like Kano, where Muslims are in the majority, political Islam rules, and Islamic theocrats deny non-believers their basic rights and freedoms with impunity.

Humanists in Nigeria are still campaigning to overturn Bala’s sentence and get the court to throw out a judgment that criminalises non-religious identities and views. Humanists are mobilising to ensure that religious and belief equality applies in Nigeria. The legal team has lodged an appeal urging the court to review and throw out the judgment. But appeal court processes are usually slow, and even slower if the process, as in this case, challenges the religious status quo. Judgment is expected in 2023 at the earliest.

Amidst this hostile environment, the Humanist Association in Nigeria (HAN), of which I am founder, organised its first naming ceremony in Benue state, central Nigeria, in September. Religious organisations have long had a monopoly over ceremonies and celebrations, including weddings, funerals, and coming of age ceremonies, but humanists are now beginning to change the narrative and to demonstrate that people can celebrate and mark events in their lives without religion. While some non-religious people do not care about celebrating the landmarks in their lives, or do not worry if such ceremonies are conducted in religious ways, many humanists yearn to mark these rites of passage in ways that align with their humanist principles and values.

However, humanists in Nigeria face opposition from families that boycott or threaten to boycott such celebrations. Religious families regard non-religious ceremonies as evil, devilish and satanic. The situation is worse in Muslim-dominated areas, because political Islam leaves no dignified political space for irreligious or ‘Kaffir’ ceremonies under sharia law. The HAN is campaigning to combat religious prejudices and misconceptions about non-religious ceremonies. It is working to dispel the stigma linked to parenting and family living without god.

In the same vein, I have been joined by a Zimbabwean humanist, Tauya Chinama, to direct another secular program, the Ex-cellence Project. This project provides social and psychological support to non-religious ex-clerics in Africa, including ex-priests, seminarians, novices, pastors, evangelists, apostles, deacons, nuns, monks, sisters, hermits, rabbis and imams. People who exit or are exited from the clergy in Africa, no matter what the religion, suffer stigmatisation. They are treated as outcasts and failures who cannot succeed in life. Ex-clerics find it difficult to integrate socially due to narratives that make them feel inadequate. Here is one story from an ex-Catholic priest, Onyeka Okorie, in Nigeria:

‘I left the priesthood in 2015. I was warned that I could not marry because any woman who married me would incur the wrath of God. I married my beautiful wife in 2016 without a single hitch anyway. They said my new family was already cursed as we had dared God, and that we would not have a child as a consequence. My wife was pregnant immediately after our marriage. They said she would not have a safe delivery, as God had to make a name for himself by punishing my wife with maternal death at childbirth. Yet my wife gave birth to our first child in 2017, our second in 2019, and our third in 2021. All of this happened without a single health or delivery issue. Now they say that my family has only three girls because God must avenge his transgressors, and therefore we will not have any male issue. What they do not know is that, as a humanist, I strongly believe that all children are equal human beings. To reject a child because it is the ‘wrong’ sex would be a gross violation of the rights of the child. I love my wife and my three beautiful daughters. They all give me joy and fulfilment that cannot be measured or valued. This part of my life story proves that religious superstition is no better than feeble myths, no matter who peddles it. Humanity reigns supreme.’

As this former Catholic priest observes, life is not easy for those who exit a religious profession, especially in a religious country like Nigeria. Ex-clerics need to be psychologically strong to cope with the pressures.

The situation is even worse for those who are driven out of the profession against their will. Former religious workers, including Sunday school teachers or those who are expelled from religious training, are demonised. The religious public sees them as existentially damned and doomed, because they have disobeyed God or have been rejected by Him; as a result, they may suffer psychological trauma. Any existential challenge that they face or encounter is seen by many Nigerians as a form of punishment from God.

In a country where religions exert considerable influence over how the state is governed and how society is organised, it is a challenge for non-religious ex-clerics to live normal lives. It is even more challenging for them to speak publicly about their lack of religion. There are no mechanisms to support and assist them as they try to reintegrate into society.

Hence ex-clerics have to resign themselves to a life of loneliness. They often suffer from mental health issues and sometimes fall into alcoholism. I have been told about some ex-clerics who suffered depression, committed suicide or attempted to do so following the exit or expulsion from their clerical job or training. In the face of such odds, clerics who lose their faith frequently feel unable to leave their profession, even when they have lost their belief.

The Ex-cellence Project exists to fill an important need, namely the provision of psycho-social support to non-religious ex-clerics in Africa. The project has been formed to correct misconceptions about clergy work and training, about exiting and being exited from the clergy, and about life after leaving religion and religious work. To further the aim of this project, a WhatsApp group has been formed which comprises non-religious ex-clerics from Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Sierra Leone, South Africa, and Germany. Virtual events will be held to give members opportunities to share their experiences and struggles living as non-religious ex-clerics in a friendly and welcoming environment. As an ex-cleric from Zimbabwe put it, ‘This initiative will help those who are stuck in religious robes against their conscience due to fear of being judged harshly by the toxic religious environment.’

Organisations like HAN and the Ex-cellence Project are a welcome development in a religiously charged and challenging environment like Nigeria. They indicate that humanism has a future here, and that some hope exists for a secular Nigeria. But these initiatives can only survive if the continual attempts by Christian and Islamic theocrats in Nigeria to overrun the country’s secular constitution and democracy are successfully resisted, and if religious tyranny and totalitarianism are deftly contained.

As it stands, Christian and Islamic theocrats are tightening their grip on the political economy of Nigeria. They have been unrelenting in stifling the rights and liberties of humanists, in eroding the secular character of the Nigerian state, and in suffocating the physical and virtual spaces for non-religious and irreligious constituencies. How far humanists succeed in combating these theocratic tendencies will determine if secularism holds any real hope for unbelievers in one of Africa’s most religious countries.

Enjoy this article? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on freethought.

3 comments

Secularism will surely survive in Nigeria. Practically all types of belief systems exist in that God’s own country. Nigerians can’t ever be suppressed.

Congratulations we have first Humanist Baby. Welcome to the World of Freedom

Please, I’m interested, I want to be a full time member.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate