What role does religion play in the Israel-Palestine conflict? Two contrasting views have recently appeared in the pages of the Freethinker. Kunwar Khuldune Shahid argued that ‘[a]t the heart of the ongoing conflict…is the fact that different religious groups are claiming exclusive control over much of the same territory’. Meanwhile, the liberal imam Taj Hargey took the opposite view in an interview with Freethinker editor Emma Park: ‘[T]he root cause of this conflict is not between Islam and Judaism, between Muslims and Jews, but between Zionist colonial settlers and the legitimate Palestinian resistance. That is the fight.’

The land where so much blood is currently being needlessly spilled is the Holy Land, sacred to the faithful of all three major Abrahamic religions, who exalt it within their respective spiritual and theological practices and traditions. Moreover, religious fundamentalists on both sides—whether in the hard right Israeli government and the fanatical religious Zionist settler movement or the Islamist outfits of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ)—continually invoke their sacred texts to justify their exclusive rights to the Holy Land. There is also a great deal of sensitivity when it comes to the use of religious sites like the Temple Mount/al-Aqsa. Given all this, it would be naïve to disregard the important part religion plays in this conflict—and it is easy to see why, in the face of such zealotry, one might see it as nothing more than a religious dispute.

Fundamentally, however, the Israel-Palestine conflict is not a holy war. Its roots lie not in supposed ancient hatreds or Quranic enmities but in modern and secular conditions. In essence, I would argue that the conflict is not, as Shahid claims, about different religious groups fighting for exclusive control of the same territory. Rather, it is a quarrel between two nations of roughly equal size—one Hebrew-speaking and predominantly (though not exclusively) Jewish, and one Arabic-speaking and predominantly Muslim, but with a significant and influential Christian minority—over who should be the undisputed master of the whole land.

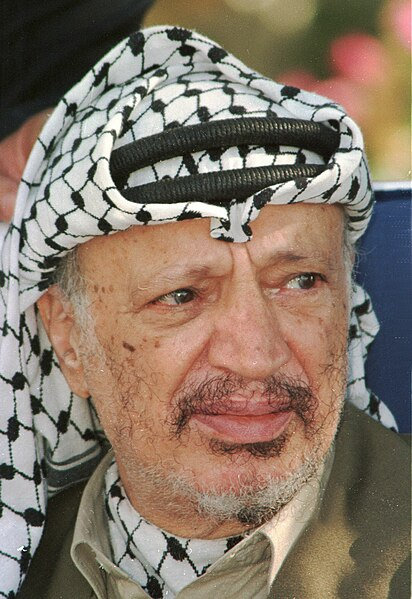

In the original 1964 charter of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), the words ‘Arab’, ‘Palestinian’, ‘homeland’ and ‘nationalism’ form a consistent motif. It does not refer much to religion, except in vague and ecumenical terms – in contrast, Hamas’ 1988 charter is replete with religious references. Moreover, in the 1970s and 1980s, the most prominent Palestinian nationalist outfit after Yasser Arafat’s Fatah was the ostensibly Marxist-Leninist (though ‘Stalinist’ would be a more apt description) Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Founded by George Habash, who came from a Christian background, many of the PFLP’s members were very secular-minded; many were even avowed atheists. It is mostly forgotten now, but when Hamas first arose in the 1980s, they would frequently clash with PFLP members, who they condemned as ‘apostates’. At that time, Israel, playing at the old imperial game of divide and rule, also implicitly backed Hamas, seeing it as a conservative counterweight to secular Palestinian groups.

The goal of leftist Palestinian nationalism is one secular democratic socialist state. This has been criticised as a Trojan horse for Arab ethnonationalist domination, but even if this was true, it would be an ethnonational, not religious, domination. It was only in 2003, under Arafat’s autocratic rule, that the constitution of the Palestinian Authority was amended to proclaim that Islam was to be the sole official religion of Palestine and sharia was to be ‘a principal source of legislation’.

On the other side, the founders of the Zionist movement, from Moses Hess to Theodor Herzl to David Ben Gurion, were, likewise, extremely secular, even anti-religious. ‘We shall keep our priests within the confines of their temples’, Herzl wrote in his infamous cri de coeur, Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) in 1896. Zionism originated in 19th-century romantic nationalism. It understood the Jewish predicament in a very particular sense. Jews were a nation in the abnormal condition of being the ‘stranger par excellence’, as the Russian Zionist Leon Pinsker put it in 1882: ‘They home everywhere, but are nowhere at home … [T]hey are everywhere aliens … [and] everywhere endangered’. Therefore the answer to the so-called Jewish question was to create a Jewish national home that would morph into a Jewish state in what they saw as the organic homeland of the Jews: Eretz Israel/Palestine.

Whether it advocated for a Jewish nation-state or a Jewish socialist commonwealth, early Zionist thought made its claims not in the name of the Jewish faith, but of the Jewish people.

Zionists heartily invoked traditional Jewish mythology and the Hebrew language, but these were subordinated to their project of national renewal. Among the first and most ardent opponents of Zionism were religious Jews who railed against the Zionist prescription of a Jewish state as a blasphemy against the Torah; in their eyes, only the Messiah (who was, as yet, still tarrying) could establish a true Jewish state. As the Israeli philosopher Micah Goodman has put it, ‘[S]ome of the main Zionist thinkers saw Zionism as a Jewish revolt against Judaism.’

Many Palestinians and Arabs find the notion of Jewish nationhood hard to swallow. To them, Judaism is just a religion; it does not denote a nation or a people. This position is also expressed in the PLO charter: ‘Judaism because it is a divine religion is not a nationality with independent existence. Furthermore the Jews are not one people with an independent personality…’ To acknowledge the secular fact of Jewish peoplehood and the depth of the historic and cultural attachment to Eretz Israel would be, to them, tantamount to legitimising Zionism, and, thus, the mass displacement and dispossession of the Palestinian Arabs in 1948 and onwards. The Israeli state’s own lack of clarity as to whether it sees Jewishness in either ethnic or religious terms exacerbates this confusion.

Zionism is not particularly unique in using religion as the external badge of nationhood. One can find a parallel (as Shahid astutely notes) in the Pakistani nationalist movement. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, its founding father, was firmly irreligious, and he argued that the Muslim population of South Asia was a particular nation that could not live as a minority under an India where the Hindu ‘nation’ was the majority. Therefore, Muslims required their own state.

Understanding the national foundation of the conflict means having a more nuanced understanding of the enmity towards Israel. Shahid claims that Islamic anti-Semitism is the ‘predominant motivation behind Muslim animosity towards Israel’. No doubt there is an element of truth to this. Religiously-motivated anti-Semitism has proliferated across many Muslim countries, as Hina Husain, for instance, has described in an article on her Pakistani upbringing. For jihadists like Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, opposition to Israel really is about ‘Muslim imperialism’, as Shahid puts it. They do not care about Palestinian nationhood; for them, Palestine is nothing more than a province in a lost empire that they wish to resurrect.

But it would be wrong to see all Arab opposition to Israel as a result of eternal anti-Semitism. The Palestinian Arab enmity towards Israel, in particular, is rooted in the concrete reality of what Zionism in practice has meant for them: the takeover of their land by newcomers, guarded by an external imperial power, to create a new political order that they would be excluded from, thus necessitating their extirpation. In other words, settler colonialism.

‘The fear of territorial displacement and dispossession was to be the chief motor of Arab antagonism to Zionism down to 1948 (& indeed after 1967 as well)’, observed the Israeli historian Benny Morris in his book Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-2001. This antagonism would have been present whatever the identity of their dispossessors—because it is a rational and materially-based antagonism, rather than a result of hideous prejudice. This is not to say that genuine prejudice has not emerged among Palestinian Arabs, just that not all of their opposition to Israel can be dismissed as such.

In this sense, Taj Hargey is right to make his parallel with settler colonialism. But this point, rather en vogue at the moment, needs more nuance. Zionism is a peculiar form of settler colonialism, because it was also a national movement of an immensely persecuted people, who were not regarded as ‘of’ European civilisation. The means of settler colonisation were used to attain the end of an independent ethnonationalist state, and the Palestinians paid the price for that.

It is also true that in recent decades, the conflict has acquired a more overtly religious character. On the one hand, we have seen the rise of religious Zionism, culminating in the ascension to power of the increasingly sectarian Benjamin Netanyahu, and, on the other, the ‘degeneration of Palestinian Arab nationalism into the theocratic and thanatocratic hell of Hamas and Islamic Jihad’ (as Christopher Hitchens put it in 2008). But even this does not negate the national basis of the conflict. It complements it. Nationalism, like religion, can be extremely irrational; it too can create ahistorical ‘sacred’ mythologies and inspire all sorts of horrors.

In essence, the Israel-Palestine question is partially an issue of settler colonialism and partially an unresolved national question. Religion is an exacerbating, toxifying factor. With the parties of God holding a veto—and exercising it liberally—over any peaceful settlement, religion has made the conflict even more intractable. One has to understand all of these dimensions as part of a whole to truly grasp the nature of the conflict.

It has become a truism to describe the Israel-Palestine conflict as ‘complex’, defying simplistic narratives. Certain things, though, such as the atrocities perpetrated by Hamas/PIJ commandos on 7 October, or the obscene bombardment Israel has inflicted on Gaza since that date, or the tyrannical Israeli occupation of the West Bank, are, however, very simple to understand and easy to take a clear position on. Still, this conflict demands a subtle yet principled approach that forthrightly opposes all racist chauvinism and religious demagoguery, whatever form it might take. Standing Together is a great civil society initiative within Israel, organised by Jews and Palestinian Arabs, seeking to promote Arab-Jewish solidarity and opposing both the occupation and extremism on all sides. This is a movement that any humanist could and should support.

Edward Said’s remark that the Palestinians are the ‘victims of the victims’ encapsulates much of the emotional intricacy underlying the conflict. In the 2015 novel The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen, which concerns itself with another protracted and deadly war, there is a passage that also sums up for me the tragedy of the Israel-Palestine conflict: ‘As Hegel said, tragedy was not the conflict between right and wrong but right and right, a dilemma none of us who wanted to participate in history could escape.’ The scars of the Israel-Palestine calamity are very deep. They will not be healed any time soon. But the fact remains: Jews and Arabs are tied to a common future in the Holy Land—a land which both belong to. The task of creating a common civic society, in which both can live as free people on a free land, may be arduous. But that does not make it any less necessary.

2 comments

Too much nuance is merely obfuscation. Religious justification for the state of Israel is nonsensical to me – all religious, supernatural belief is. Millenia of murder, theft, and expulsion convinced Zionists they needed their own country. Through luck and hard work they got it. I support them in keeping it. The only justification needed is the right of survival.

Blame for the “obscene bombardment” since Oct. 7 belongs on Hamas, Iran, and maybe just a little on the wider world that opposed Israel achieving decisive victories in several previous conflicts. Israel absorbed 700,000 Jewish refugees expelled from Arab and Islamic countries following 1948. Why couldn’t and can’t the Arab world solve the “Palestinian problem” rather than letting it metastasize even further?

There are many well known attempts “to do the arduous work of making a common civic society” by Israel – typically met with rejection by the Arabs and always by the Palestinian leaders. Siding with the appeasers is not far short of asking for the Jews to march into the sea. If that’s your solution, please say it out loud.

Herzl understood the need to have a major world power backing the zionist project.

For reasons connected with reverses suffered in World War One, this backing came in 1917 from the British Empire in the form of the Balfour Declaration.

During the British Mandate Palestine era (1918-1948), Britain permitted unparalleled levels of inward Jewish migration into Palestine.

The Zionist uprising and Nakba of 1948 effectively meant that the zionists double-crossed the British by driving them and half the Palestinian population out.

After 1948, the zionists switched their “allegiance” to the US Empire.

However, as recent events have indicated, the zionists are currently double-crossing the Americans today, just as they did the British in 1948.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate