‘That which I greatly feared had at last come upon me’ wrote C. S. Lewis of his conversion to Christianity in Surprised By Joy. ‘In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England.’ Like most new Christians, Lewis converted because he had become convinced of the truth of the Scriptures and felt a connection with the God of the Bible. He went on to become the most famous Christian apologist of the twentieth century, always arguing in support of a literal, real and personal God.

In the twenty-first century, the God of the Christian Bible has found new defenders. Unlike Lewis, they do not argue that he is real. Rather, they argue that he is necessary. More specifically, that he provides our civilisation with its ethical foundations, and without him, we face nihilism. New Atheism ‘inherits a vague rational humanism that it has to pretend is natural, or common-sense,’ wrote Theo Hobson in Spectator. ‘It’s an important task of Christian apologetics to point this out, to insist that the moral assumptions of our culture have Christian roots.’

‘Atheism can’t equip us for civilisational war’ was Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s position in her article on her conversion to Christianity, published in November 2023 in UnHerd. Referring favourably to Tom Holland’s Dominion, she wrote that ‘all sorts of apparently secular freedoms — of the market, of conscience and of the press — find their roots in Christianity.’ Ali does not mention accepting Christianity’s metaphysical claims in the article.

Perhaps no public figure has become more associated with this argument than Jordan Peterson. Peterson does not appear to believe in a literal supernatural being, but believes that the secular ethics of the modern west are based in Judeo-Christian values and it would be better if we acted as though the Christian God did exist. ‘What else do you have?’ he demanded of sceptical young men in his 2022 message to Christian churches. And, to those who might respond by saying that they do not believe in the doctrines of the Church, ‘who cares what you believe?’

This argument is made by conservatives and directed at a specific audience: non-religious people sceptical of modern progressivism. Christianity, they argue, provides a bulwark against geopolitical threats like Islamic fundamentalism and China, and against the extremes of ‘woke’ culture. I have not heard left-wing Christians argue that only Christian ethics provides a basis for demanding that the rich give away their wealth and care for the poor, although such an argument would be similar.

There are a few problems with this claim. Proving that Christianity is influential would not prove that its supernatural claims are true, and visa-versa. For this reason, atheists of different political opinions do not find the argument satisfactory. Secular humanist Matt Dillahunty had a lengthy debate with Peterson which left him, as he later told Douglas Murray, ‘confused and more than a little irritated.’

‘I want to believe as many true things and as few false things as possible,’ Dillahunty said, explaining that things were true or not based on whether they comported with reality. The usefulness of God is irrelevant to his existence.

It is also unsatisfactory to the conventionally religious, for similar reasons. ‘Contra Peterson, the story of Scripture was not written in philosophical abstracted metaphor, but in real time, space and blood,’ wrote Dani Trewek for Gospel Coalition, a gospel advocacy group based in Australia, in 2022. ‘It is not ultimately concerned with the earthly “optimisation” of created man, but the eternal glorification of the Son of Man.’ Again, God’s usefulness is irrelevant to his existence.

Even if the argument were sound, it is not clear what we would do about it. Christianity might, as Ed West put it in Spectator, ‘meme itself back into existence’ if we all go through the motions, but it is hard to see people being persuaded into accepting the supernatural for political reasons.

I want, though, to focus on a particular problem with the argument: that it overstates the continuity of Judeo-Christian ethics. According to Genesis, God created man in his image – yet the morality of the Bible is not humanist. The Ten Commandments condemn disbelief and sabbath-breaking before murder; Leviticus and Deuteronomy are filled with condemnations of ritual offences, but permit slavery and treat women as property.

Let us look at one specific case. Writing on heresy in Summa Theologica, Thomas Aquinas accepts that heretics should be put to death. He favourably quotes Saint Jerome verbatim on the way heretics should be treated: ‘cut off the decayed flesh, expel the mangy sheep from the fold, lest the whole house, the whole paste, the whole body, the whole flock, burn, perish, rot, die.’ Aquinas’ position is consistent with Scripture. The God of the Bible collectively punishes societies for tolerating sin, floods the earth, rains down fire on Sodom and Gomorrah, and allows the Babylonians to march the Israelites into captivity when they fail to self-police their morality. Aquinas’ position was uncontroversial in the medieval and early modern church.

Today, however, this position is repugnant to us, including among the devoutly religious. Morally, killing someone for their religious beliefs strikes us as murder. And practically, if we had kept the death penalty for heresy, we could never have achieved what we have in philosophy, science, literature and art. A society that burns heretics is doomed to stagnation. The idea of killing an individual to protect the morals of society as a whole is fundamentally incompatible with liberalism.

In many ways, traditional Judeo-Christian ethics are as different from modern secular ethics as Sharia law is. This is not to condemn them for being unusually bad: most pre-modern ethical codes are based in similar principles. But it does ignore the massive break with the past represented by the Enlightenment, which saw the concomitant rise of liberalism and the creation of the modern concept of human rights. In practice, the advocates of the ‘necessary’ Christian God are dining at an ethical buffet, picking and choosing from the Scriptures and the writings of theologians according to taste.

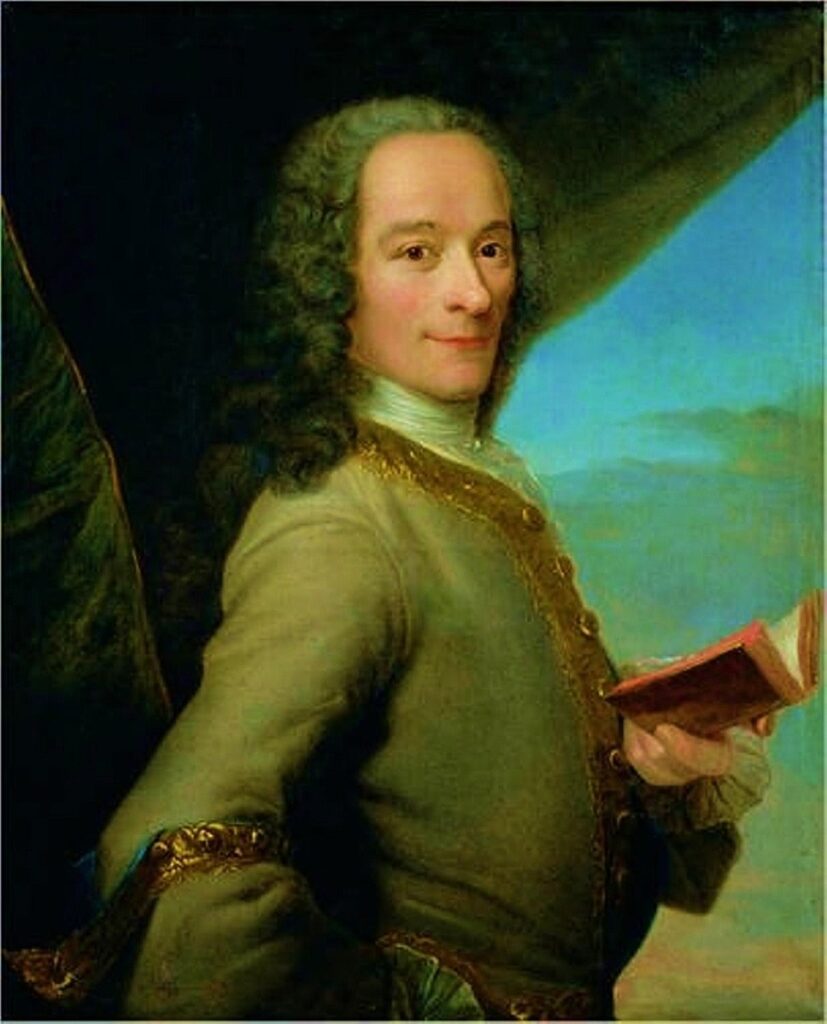

Ultimately, there is a false dichotomy between faith, or at least the appearance of faith, and nihilism. We can – and should – consider ideas on their own merits. Those for whom faith is real and personal will believe. But those who are not persuaded by metaphysical arguments will not be persuaded by political ones, and nor should they be. Voltaire was alleged to have quipped that he did not believe in God but hoped his servant did so she did not steal his silver; the modern argument for the ‘necessity’ of Christianity, when it is boiled down, looks similar. By comparison, I actually prefer C. S. Lewis’ straightforward and direct approach.

Anyone who appreciates the benefits of living in a modern Western country can look to the tested and proven principles of the Enlightenment, the Scientific Revolution, constitutional government and human rights. If someone wants to believe in the Christian God and in the values of the Bible, that is fine – but it is not necessary.

See also: What has Christianity to do with Western values? by Nick Cohen

3 comments

“Morally, killing someone for their religious beliefs strikes us as murder.”

How about handing your own child over to the village elders to be stoned to death for the crime of backtalking? See Deuteronomy 21:18.

I agree with your concluding paragraph but when referring to the “Christian God and the values of the Bible” I think you need to distinguish OT from the NT. As Prof Stavrakopoulou put it, the ancient God of the OT (supersized, muscle-bound, human-shaped “with a penchant for the fantastic and monstrous”) has long been theorised away and replaced by a lifeless, abstract deity worshipped by Christians and Jews today. In contrast, the God of the NT as represented by Jesus is a completely different being and his values (Sermon on the Mount etc) are what the West has essentially absorbed and built on in varying ways. As an atheist I haven’t got a problem with that, nor with Holland’s central premise in Dominion.

As for Peterson, the man has completely lost the plot. Once upon a time he had some interesting things to say (and I liked his mantra to confront chaos, get on with it and “quit whining!”), but now he sounds like a second-rate, soapbox preacher. His muddled and condescending ‘Message to the Christians Churches’ is just awful.

It all boils down to some people’s need for a third sanctity to organise one’s chaotic true self. As a devoted atheist, I am quite happy without resorting to any ‘god’ for upholding my conscience and providing me with “life after death”, which is a complete bullshit.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate