A previous article of mine mentioned a number of pitfalls into which many philosophers have fallen over the millennia. But what of those who have, more or less, overcome the philosopher’s curse(s)?

The Modern Cosmopolitan

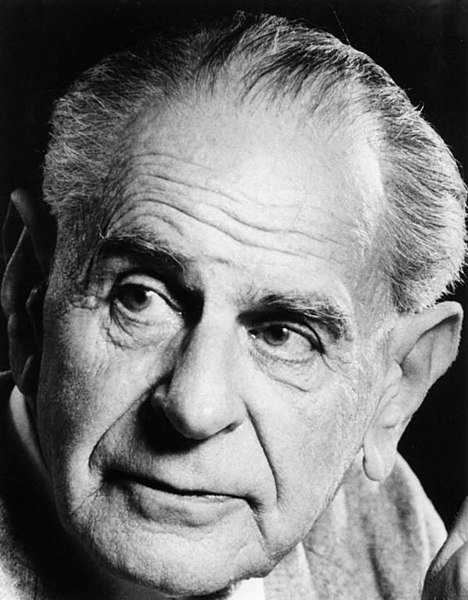

If pressed to name a philosopher who stands for sensible, resolutely non-mystical while deeply probing thinking, Karl Popper comes eminently to the fore. If, in addition, the search is for a thinker who confronts and makes advances in concrete issues, not just in philosophy but in society and in politics; and further, if someone is sought who made it a point to produce writing that is sturdily clear, Popper keeps, well, popping up.

He may well have been the most important philosopher of the twentieth and, so far, twenty-first centuries. And yet he was the very model of the philosopher who doesn’t assert what he or she imagines to be the definitive position on anything. His basic attitude is no more than that of proposing something that he considers workable, rather than laying down the law—a welcome attitude in philosophy (and, it goes without saying, further afield too). Popper’s writing is peppered with phrases like ‘where we believed that we were standing on firm and safe ground, all things are, in truth, insecure and in a state of flux’ and ‘most of our theories are false anyway.’

No, in the above statement on Popper’s importance, I did not overlook Wittgenstein, his old nemesis. Nobody made more significant contributions than Popper (and in more fields than Wittgenstein); the difference was that W. had charisma, which to P.—who didn’t—was a big irritant. In any case, their rivalry—which reached its high point in the famous episode with the poker—was a great pity, since they had so much in common. Not just that both were brilliant Viennese philosophers from wealthy, cultured Jewish families (although the Poppers were ‘merely’ rich, and the Wittgensteins were the Rockefellers, update that to the Bill Gateses, of Austria), but they were both enrolled in the same good cause, that of ridding philosophy of mumbo-jumbo and baseless dictums.

The above phrase ‘their rivalry’ perhaps requires some qualification: it was Popper who felt it was a rivalry, while Wittgenstein hardly considered him or anybody else to be his rival—virtually the only real intellectual respect he felt was for Bertrand Russell.

Popper’s texts are so clear that one may sometimes get the impression that one is reading a dumbed-down version of them, but that was just the way he wrote—and thought. One of his principal, and best-known, advances was to establish that what allows a statement to be considered scientific isn’t, as was commonly thought, that it be verified by experiment, but that it be possible, at least in principle, to try to disprove it experimentally (as opposed to metaphysical and mystical propositions, which can’t). Sometimes this ‘falsifiability’ principle has been likened to the earlier ‘fallibilism’ of Charles Sanders Peirce, although fallibilism seems closer not to this specific epistemological tool but to Popper’s overall position that our knowledge is fundamentally uncertain. In any event, Popper admitted that he wished he had known Peirce’s work earlier—and went so far as to write that Peirce was ‘I believe, one of the greatest philosophers of all time’.

Always wary of unforeseen, unintended consequences, in practical politics Popper showed the virtues of piecemeal, careful improvements above all-at-one-stroke ‘utopian engineering’.

He also had an answer to those who held that the falsifiability criterion was useless because any theory refuted by experiments could nevertheless be propped up by introducing additional hypotheses (‘It didn’t really fail, it’s just that there was an external factor that modified things’). He said: ‘As regards auxiliary hypotheses we propose to lay down the rule [notice the ‘propose’] that only those are acceptable whose introduction does not diminish the degree of falsifiability or testability of the system in question, but, on the contrary, increases it.’ His theory of knowledge was, essentially, that it advances by making conjectures, based on any source at all, and then submitting them to criticism (and after stating this theory he characteristically added, ‘which I wish to submit for your criticism’.)

Always wary of unforeseen, unintended consequences, in practical politics Popper showed the virtues of piecemeal, careful improvements above all-at-one-stroke ‘utopian engineering’. He dug political theory out of a morass born of a demoralising realisation about democracy, namely that people are capable of democratically voting for a Hitler or for religious extremists. He did it by pointing out that the key to a democracy, even above formal conditions such as the separation of powers, is to have mechanisms that don’t allow rulers who turn out to be incompetent, larcenous, or dictatorial, to do too much damage. It isn’t elections that define a democracy, he taught, but containment afterwards.

Popper championed freedom—his major book on this subject being titled The Open Society and Its Enemies—yet cautioned against ‘unrestrained’, i.e. entirely free, capitalism. He wasn’t perfect (he had all along been saying that nothing is). He could be self-aggrandising, aggressive, and hurtfully dismissive. In inviting criticism professionally, he was Dr Jekyll; in responding to it in person, he was Mr Hyde. He could also contradict his own thinking: take the just-mentioned issue of capitalism. His stance was that it was the state’s duty to defend the weak and poor, and wrote that ‘we must demand that the policy of unlimited economic freedom be replaced by the planned economic intervention of the state.’ And yet, out of his fervid anti-communism (based partly on errors he detected in Marx and very strongly on the dictatorial nature of the Soviet Union), he ended up not raising an almighty fuss when his teachings were misappropriated by Margaret Thatcher, the heartless and supreme political champion of untrammelled capitalism.

Then there was his fiercely critical attitude towards Israel. Popper never managed to get over the shock, as someone who grew up feeling entirely assimilated into mainstream Austrian society, of being pigeonholed as Jewish by the Nazis. It left him unwilling to even try to understand Israel’s dilemma, that of having to defend its very existence even as it was attempting to very hurriedly yet democratically work out its ultimate identity. This is a process that has normally taken nations scores or hundreds of years—he might have considered the case of his own country, Austria.

Popper must have known that Israel was born containing a welter of groups pushing wildly different interpretations of what it should be, including an intractable ultra-religious minority holding the balance of power. And yet over time, whilst permanently threatened by Arabs from outside, Israel actually increased, not decreased, the participation of its native Arabs in its institutions. Maybe it was Popper’s own past identity flux that led him to censure the Jews of Israel with startlingly disproportionate harshness. In any case, there is a time-hallowed, sadly applicable word that, among its meanings, includes that of finding far more fault with Jews than with others acting comparably or worse. That word is anti-Semitism.

The Ancient Savant

In a time long before and a country far away, there lived another thinker who deserves to be singled out for appreciation as a philosopher utterly determined to root out the bogus: Wang Chong (27 – c. 97 CE).

Not just clear-sighted, Wang Chong (alternative transliteration: Wang Ch’ung) was also courageous in a way that we today cannot—and thankfully need not—emulate (unless, of course, we happen to live under a fundamentalist religious regime and want to let it be known that we are deep-down sceptics who reject hocus-pocus and intend to subject received tenets to hard scrutiny).

In fact, for us, it’s easy not only as regards the politics (with the above reservation), but as regards the actual thinking. We can rely on all the demystifying work done by many notable philosophers and scientists in recent centuries. Wang, on the other hand, lived anciently—the precisely two-thousandth anniversary of his birth will take place three years from now—and in a China (in his case, under the Han dynasty, in its second or Eastern phase) that was steeped, as it almost always has been, in a culture of unquestioning obedience to power and obeisance to sacrosanct texts. His dubiousness had only a few thin precedents to go by. (By the way, the British new wave band Wang Chung, whose name gets prominent screen display in the recent film The Idea of You, was definitely not named after the savant.)

Our Wang was a Renaissance man avant la lettre, an encyclopaedic historian, astronomer, meteorologist, physicist, and so on, as shown in his compilation text Lunheng (variously rendered as ‘Measured Treatise’, ‘Disquisitions’, ‘Discussive Weighing’, ‘Balanced Discussions’, and other titles). But it was as a philosopher, one stubbornly unimpressed by authority, whether philosophical or political, that he most impresses us today.

Wang remained tied to a number of prevailing concepts, although he criticised and, when he saw the need, modified them—like destiny (ming) and vital energy (qi). But here’s the crucial thing: he demanded proofs for affirmations, spurned superstitions, belittled supernatural explanations, and dismissed the belief that things only happen because they are preordained. He held truth even above tradition (gasp!). The official worldview in his China was positively Panglossian (again, avant la lettre), the epitome of wishful thinking, in the sense that what was regarded as ideal was thought to be actually the case. For example, the worthy person will no doubt get ahead: it ain’t necessarily so, sang Wang. Good deeds are inevitably rewarded and bad ones punished: hardly, noted Wang. If the ruler is a good person and is happy, prosperity will necessarily smile on his subjects and even the climate will be benign: just not so, declared Wang.

And this is amazing: he got away with it. He wasn’t decapitated, or forced to drink hemlock (as Socrates had been 400 years earlier), or ordered murdered by his own son because his thinking was too free and offended religion (as happened to the great astronomer-mathematician Ulugh Beg of Samarkand 1,300 years after Wang’s time), or stabbed in the eye (as well as various other parts of the body, as happened to Salman Rushdie all too recently). While the year of his birth is generally accepted to have been 27 CE, so peaceful and unremarkable was his death that its date is only approximately known, set as c. 97.

Wang Chong. Here was a person who truly thought freely.

East, West

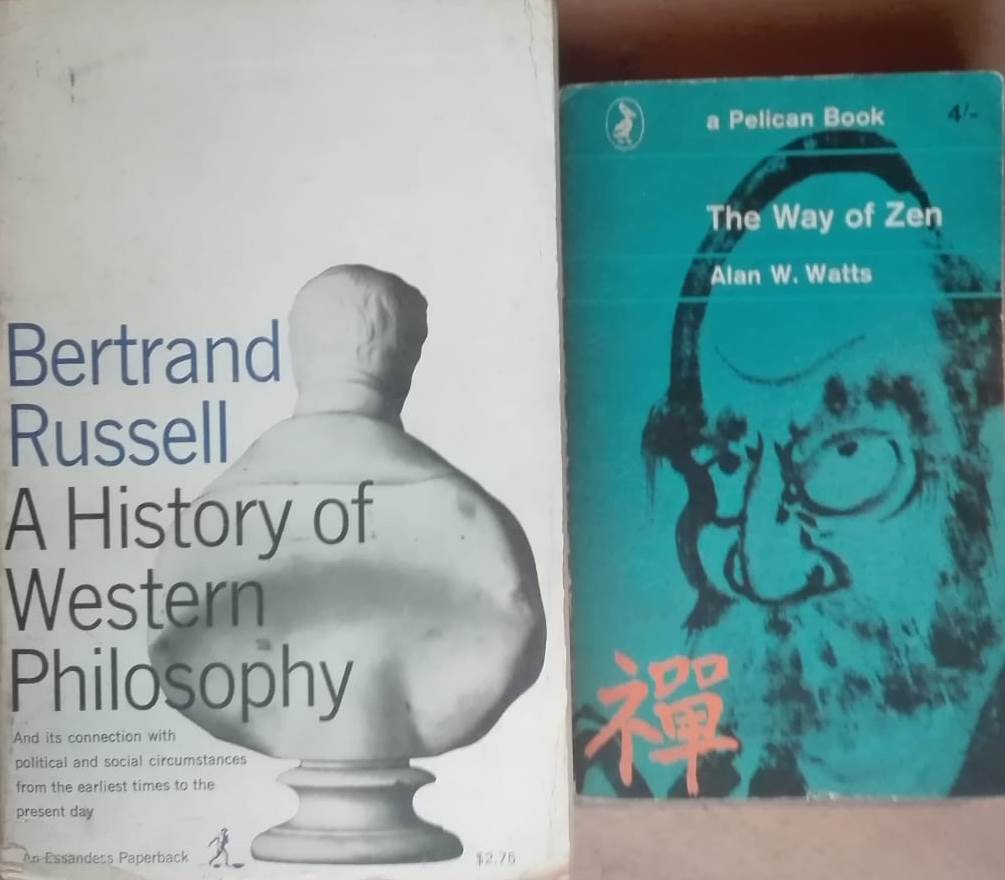

To complement the praise-fest, here are two thinkers (in a way, diametrically different from each other) whom I cherish specifically as historian-commentators of philosophy. People who don’t care to go into any one Western philosopher’s thinking in great detail but could use a very pithy one-volume overview of it all can be directed to Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy (1945). Alan Watts, even in a slim book like The Way of Zen (1957), elegantly renders a similar service as regards the East.

Russell was, of course, himself a towering figure in philosophy as well as mathematics. In A History, he brings his big brain to bear on philosophy’s past—seeking to put it in its historical context—and he doesn’t just set forth the diverse thinkers’ positions. He gives his own assessments—and his commentaries can be acid. Kant, he says, ‘is generally considered the greatest of modern philosophers. I cannot myself agree with this estimate…’ Of Hegel’s Philosophy of History he writes, ‘Like other historical theories, it required, if it was to be made plausible, some distortion of facts and considerable ignorance. Hegel, like Marx and Spengler after him, possessed both these qualifications.’

And yet he is scrupulous in pointing out meritorious aspects even among theories he finds fault with. One complaint that can be made is that, with quite uncharacteristic modesty, he is comparatively, and disappointingly, brief about what he calls ‘the philosophical school of which I am a member’—logical analysis.

One way to describe the task pursued by logical analysis, and the overall current it forms part of, is (in loose terms—not Russell’s own), ‘Let’s sweep away the twaddle.’ Russell did a lot of sweeping himself. Alan Watts, on the other hand, is—how to put this?—in a different tradition. He is selling mysticism and ‘don’t think, float along’ elixir by the barrel. The reason to turn to him, as suggested above, is to obtain a compact outline of philosophical thinking, Eastern division. This he provides: in order to put the Zen in the mentioned book’s title in context, he gives a genial guided tour of Hinduism, Taoism, and Buddhism in general.

Watts writes with style and clarity—and affably works every gram of reasonableness he can into the narrative. His tone is quite the opposite of the sanctimoniousness his largely religious subject matter might tempt him into.

Zen is about gaining ‘Wow, I suddenly see it!’ moments. A personal takeaway: The Way of Zen not only describes such events, but actually generated one in me—with the small catch that what I suddenly saw wasn’t what Watts intended.

It concerned the issue of spontaneity. The Eastern philosophy that Zen distils sets enormous store by spontaneity; acting on reasoned decisions is for the unenlightened. In consequence, devotees strive strenuously to achieve that ideal attitude. Unfortunately for them, this is self-defeating—since striving for something is precisely the opposite of being spontaneous about it. But it turns out Zen has a wonderful solution up its sleeve. Can you help it, it asks the victims of this trap, if you can’t stop striving? No? Then your striving is itself spontaneous! So you have been spontaneous all along! Watts quotes a Zen master: ‘Nothing is left to you at this moment but to have a good laugh.’

The cleverness of the table-turning bowled me over. Wow, I suddenly did see something: namely, that with gambits like that, one can let oneself off any mental hook.

One can get away with anything!

Some philosophy-related further reading

‘The Greek mind was something special’: interview with Charles Freeman, by Daniel James Sharp

Consciousness, free will and meaning in a Darwinian universe: interview with Daniel C. Dennett, by Daniel James Sharp

Atheism, secularism, humanism, by Anthony Grayling

A French freethinker: Emile Chartier, known as Alain, by Michel Petheram

‘When the chips are down, the philosophers turn out to have been bluffing’: interview with Alex Byrne, by Emma Park

‘The real beauty comes from contemplating the universe’: interview on humanism with Sarah Bakewell, by Emma Park

On sex, gender and their consequences: interview with Louise Antony, by Emma Park

Image of the week: Anaxagoras, by Emma Park

Image of the week: Portrait bust of Epicurus, an early near-atheist, by Emma Park

Can science threaten religious belief? by Stephen Law

Lifting the veil: Shelley, atheism and the wonders of existence, by Tony Howe

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate