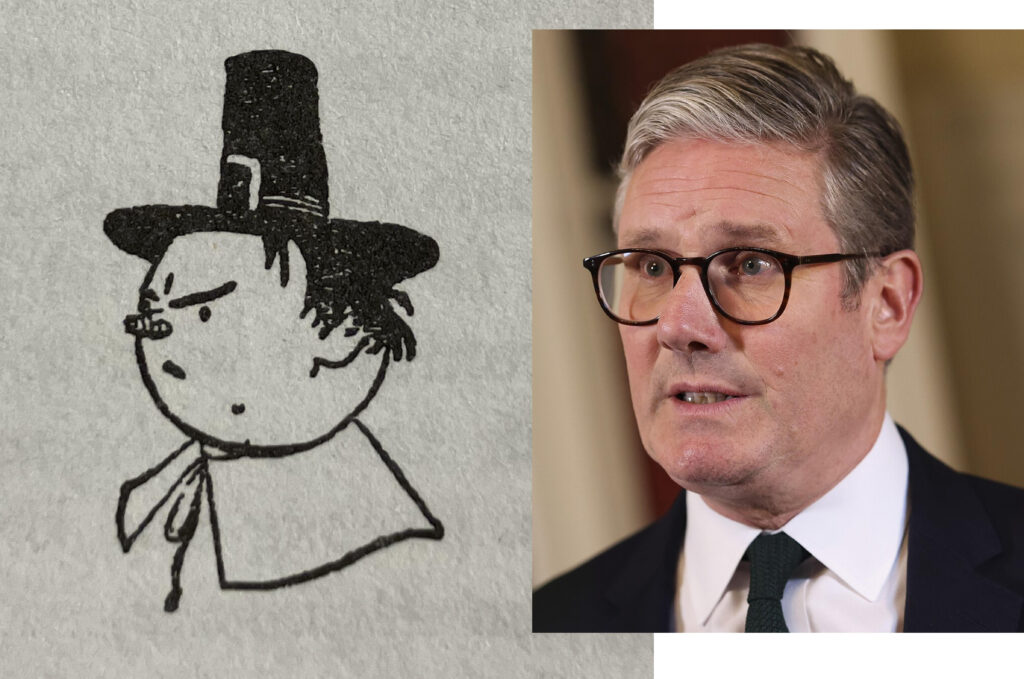

When Keir Starmer called for ‘an immediate ceasefire in Gaza, the return of the sausages––the hostages’, the expression on his pasty visage, which some have compared to a pork pie with designer glasses, was one of dismay. If, contrary to appearances, his defining characteristics included humour, you might have thought that the Prime Minister was making a subtle reference to that classic of British ante-post-colonialism, 1066 and All That. It is the sort of flippant allusion a certain predecessor of his might have made in one of his ill-starred attempts to lighten the mood.

Written by W.C. Sellar and R.J. Yeatman, illustrated by John Reynolds, and first published in 1930, 1066 was a parody of the school history textbook of its day—or perhaps more accurately, of a schoolboy’s recollection of his history lessons. It claimed to comprise ‘all the parts you can remember, including 103 Good Things, 5 Bad Kings and 2 Genuine Dates’. Its 62 chapters each end with a ‘test paper’ full of baffling questions: ‘Has it never occurred to you that the Romans counted backwards?’ ‘Why on earth was William of Orange?’ ‘N.B.’ warns one test, ‘Do not attempt to answer more than one question at a time’—also good advice for politicians. If it be permitted to compare great things with small, this ‘slim volume’ is almost as meta-literary as Tristram Shandy, with its ‘Compulsory Preface (This Means You)’, fictive ‘Press Opinions’ (‘“…vague…” (Vague.)’) and ‘Acknowledgements’ to editors of learned journals ‘in which none of the following chapters has appeared’.

Its relevance to Sir Keir’s gaffe, however, is in its list of ‘Errata’, on page vii: ‘For sausage read hostage.’ The erratum itself occurs on page 44: ‘Henry IV Part II…also captured the Scottish Prince James and, while keeping him as a sausage, had him carefully educated for nineteen years’. Apparently, the two words are just doomed to confusion.

Of course, there is something inherently silly about sausages, both the word and the thing in itself—and yet, at the same time, something homely and comforting. No wonder Sir Keir’s subconscious mind, under so much pressure on the fraught Israel-Palestine question, reached for a substitute. Similarly, in 2017, Andrew Neil’s id cried ‘Breakfast’ when his superego was toiling in vain to stay with Brexit. (The Errata also direct: ‘For Pheasant, read Peasant, throughout.’ If Starmer, following in Blair’s footsteps, launches a second crusade for animal welfare in the countryside, perhaps he will try to ban ‘peasant hunting’.)

It is therefore most uncharitable of the Guardian to draw a comparison between our PM’s sausages slip and the blunder made by Mr Biden, who in July mistook the president of Ukraine for his Russian foe. Everyone knows that it was only by a laughable administrative error that America’s 46th President was still in the White House at the time, rather than a nursing home. Surely the Guardian does not think that Sir Keir ‘Sausage’ Starmer is that far gone yet.

Sadly, if 1066 were still popular today among anyone apart from a few history teachers and other nerdy fans, it would already have been cancelled, or at least bowdlerised out of recognition. Its premise is that there is a ‘History of England’ with which its audience would all be familiar. Yet it is unclear whether such a shared body of cultural knowledge still exists in modern Britain—if it ever did. The book’s whimsical humour oscillates haphazardly between the puerile, the dated, the obscure, the silly, and the pure genius; it freely confuses causes and effects, facts, quotations, history, and literature; and is doubtless an acquired taste. A modern sensitivity reader would barely need to open it to start making accusations of racism, sexism, imperialism, homophobia, etc, etc, even though its effect is usually tongue-in-cheek. (For instance, Chapter LVI contains a list of ‘Justifiable Wars’ in the Victorian period whose purpose was to ‘amuse the Crown’, including ‘7. War against Zulus. Cause: the Zulus. Zulus exterminated. Peace with Zulus.’)

Yet despite its many sins, it is respectfully submitted that Sir Keir might read 1066 with profit. In particular, for the dates. Aside from the one in the title, the other date in ‘English History’ is (of course) 55 BC,

in which year Julius Caesar (the memorable Roman Emperor) landed, like all other successful invaders of these islands, at Thanet. This was in the Olden Days, when the Romans were top nation on account of their classical education, etc.

Using their STEM skills, Starmer and his team should be able to calculate that this happened approximately 2,000 years ago, or about 1,000 years before the Norman Conquest. Now, of course, speaking in Sellar-and-Yeatman terms, it took a few more centuries for the Greeks to degenerate into Byzantinists, and the Romans into Catholics. But the basic point remains: the Greeks and Romans were ancient, the Normans medieval.

Hopefully, this reminder will enable Sir Keir in the future to avoid confusion between these two periods, so critical in our glorious, much-colonised past—contrary to the impression he gave in his speech at the Labour Creatives Conference in March. A practised note of indignation crept into his voice as he observed that the Tories’ EBacc qualification ‘values Latin and Ancient Greek but not music, drama or art’. A damning indictment indeed, which he descanted upon in a sort of free verse:

‘Seriously—in what world does learning to act, dance, sing, or paint…

‘Count for less than learning a language from more than 1,000 years ago?

‘The ancient Romans and Greeks would have had something to say about that!’

Which leads to a ‘test paper’ question especially for him:

- To what extent were the Romans the real conquerors at the Battle of Hastings? Are you sure?

In the final chapter, entitled ‘A Bad Thing’, the authors conclude that ‘America was thus clearly top nation’, bringing History, and their history, abruptly ‘to a .’ These days, totting up scores between competing superpowers is passé (who is ‘top nation’ anyway—China?). Instead, the brave new historian must determine who is on the Right Side of History. Often it is activists of one stripe or another (climate protesters, students, filmmakers) on whose behalf this claim is made. As the historian RJ Evans has pointed out in the New Statesman, similar assertions have also been made by leaders Good and Bad (in 1066 terms), from Hitler to Castro, Obama to Humza Yousaf. In the endless agonising over the position that Labour should adopt on the Israel-Palestine conflict, Sir Keir has more than once been urged to take steps that would put him on the ‘right side of history’. Yet such moral rhetoric is not only self-serving, but, by this stage, has degenerated into little more than a tired cliché.

As 1066 and All That states in its Preface, ‘Histories have previously been written with the object of exalting their authors. The object of this History is to console the reader. No other history does this.’ If only Sir Keir and his Party could take a leaf out of Sellar and Yeatman’s book, and, instead of being so relentlessly Right but Repulsive, embrace the consolatory side of things—sausages included.

1 comment

I used 1066 and All That as a pattern for my “O” Level History revision; the subject was still taught that way in my schooldays. Since then I have given many copies as presents. Alas, it seems that the subject is no longer taught in that style so the book’s days might be numbered.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate