Books From Bob’s Library is a semi-regular series in which freethought book collector and National Secular Society historian Bob Forder delves into his extensive collection and shares stories and photos with readers of the Freethinker. You can find Bob’s introduction to and first instalment in the series here and other instalments here.

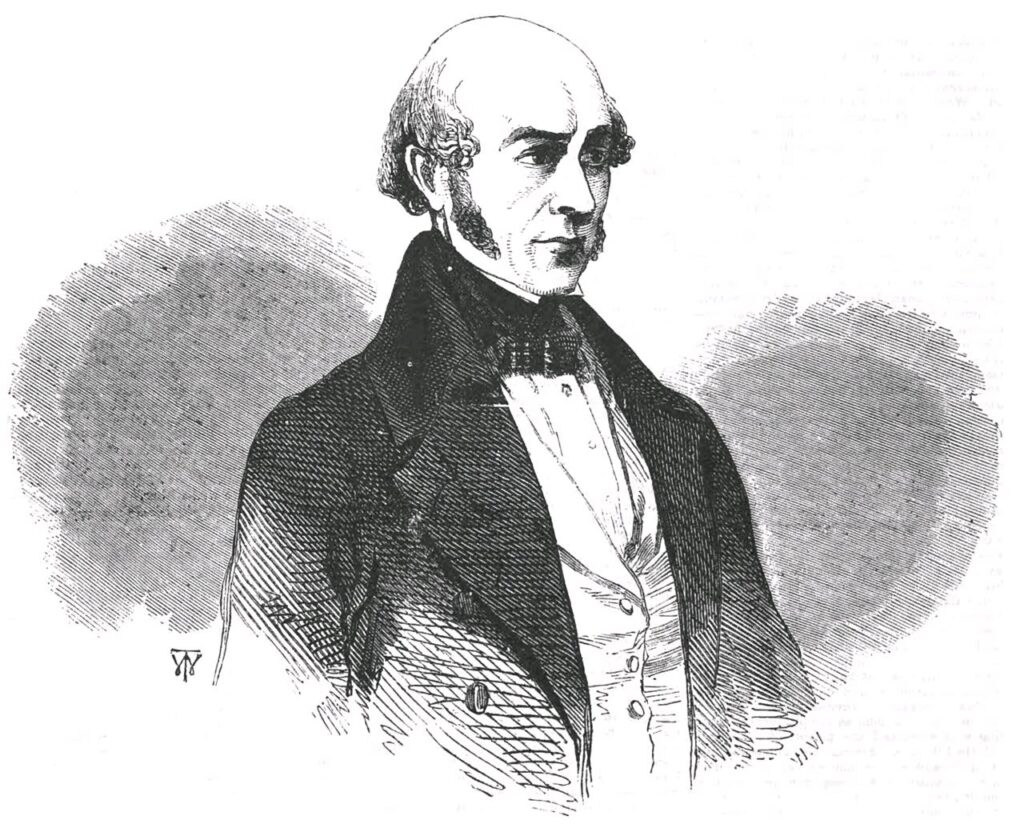

There are several reasons for selecting Henry Hetherington as the fifth subject of this series. The most immediate, however, is the recent publication of Adrian Desmond’s Reign of the Beast: The Atheist World of W. D. Saull and his Museum of Evolution. While the primary focus of this extraordinary book is the life and work of William Devonshire Saull, it also rescues from obscurity some remarkably brave and largely forgotten freethinkers and radicals whose lives have changed the way we think. Henry Hetherington is an outstanding example; he features as one of Saull’s leading allies, friends, and collaborators. (As it happens, Michael Laccohee Bush recently reviewed Desmond’s book for the Freethinker.)

Hetherington was born in 1792 in Soho and as a youth, he was apprenticed as a printer. On completion of his apprenticeship, he travelled to Belgium in search of work. At this time, Brussels was a prominent centre of radicalism and this undoubtedly influenced him; he began to move in radical circles. A couple of years later, he was back in London and in 1822 registered his printing press at 13 Kingsgate Street, Holborn.

By now he was married and was to father nine children, although only one son survived him. He joined a small group called Freethinking Christians, who were attempting to reconcile Christianity with scientific advances, but he fell out with them over their refusal to admit a Jew. In 1828, he published his first pamphlet, Principles and Practice Contrasted; or a Peep into “the only true Church of God upon Earth,” commonly called Freethinking Christians. Here, Hetherington poured scorn upon the sect, describing them as ‘the most skilful and consummate hypocrites of the present day’.

Hetherington, unlike Richard Carlile, was to emerge as a class warrior and became a dominant figure in the National Union of the Working Classes, as well as other organisations and campaigns promoting loosely socialist causes. He was much influenced by the principles of Owenite socialism and cooperation. In concert with this, a constant stream of books, pamphlets, and periodicals poured from his press on every important political, social, and religious question of the day. Most important amongst this paper blizzard was his journal The Poor Man’s Guardian.

In 1830 Hetherington began his long struggle to free the press from the payment of the stamp duty by publishing the first number of A penny paper for the people by the Poor Man’s Guardian. The paper should have retailed at 7d, including the 6d stamp duty. These duties had been introduced with the purpose of repressing radical ideas and newspapers for working people by inflating their prices so they could not be afforded. Hetherington was arrested within forty-eight hours and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment.

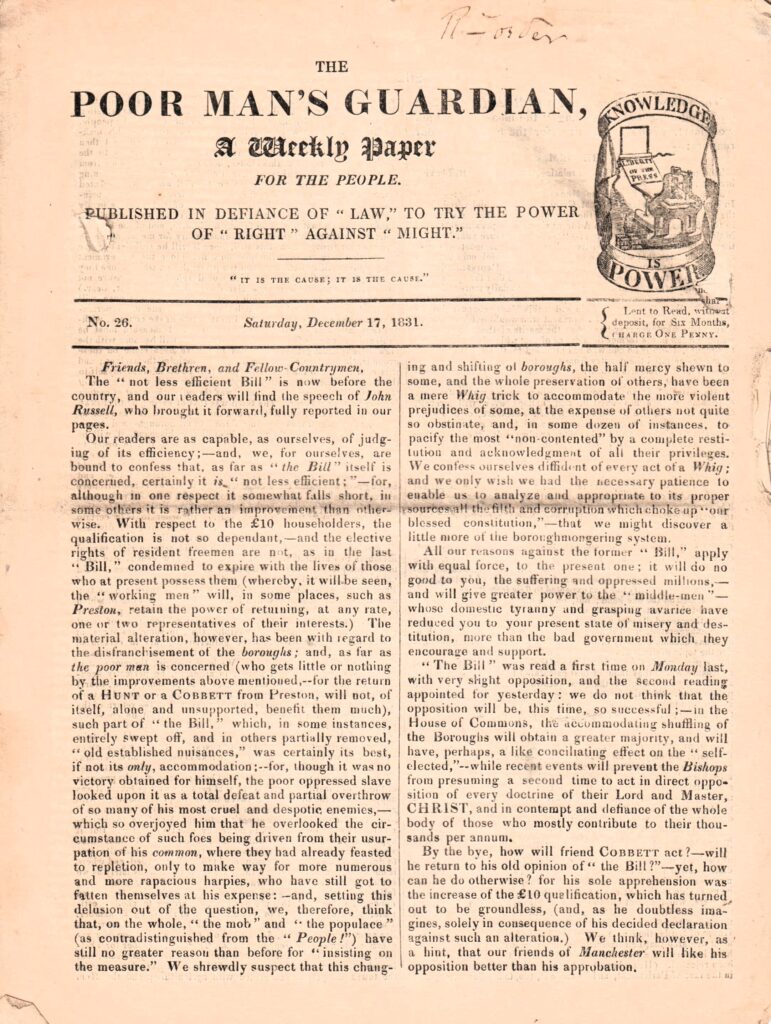

On 19 July 1831, Hetherington recommenced publication under the title The Poor Man’s Guardian. I had never seen a copy outside of a library, but recently I spotted one for sale at a reasonable price. Imagine my amazement when I opened the package to see the signature of my ancestor above the masthead! He had been secretary of the National Secular Society (NSS) in the Bradlaugh years and a publisher of freethought and birth control literature in his own right towards the end of the century. This does say something about the roots of the NSS in Paine-ite freethought and working-class radicalism. I have checked the authenticity of the signature against correspondence in my possession.

My Poor Man’s Guardian from December 1831 reported on the struggle for the Reform Bill, which was to become law in 1832 (the Great Reform Act) whereby some limited changes were made to the franchise and electoral system. The usual conclusion is that the reforms went nowhere near far enough to meet the demands of radicals but did demonstrate that reform was possible without revolution. This defused some of the aspirations of those who would have chosen that route and influenced subsequent radical and freethought leaders such as George Jacob Holyoake and Charles Bradlaugh, who always taught that radical change and social improvement could be achieved peacefully through the parliamentary system.

Some important features are worthy of note. The ‘strapline’ reads ‘Published in Defiance of “Law,” to try the power of “Right” against “Might.”’ In the place usually occupied by the stamp, and designed to imitate its shape, is an illustration of a printing press bearing the words ‘Knowledge is Power’ and ‘Liberty of the Press’. Finally, where you would expect to find the sale price, there are the words ‘Lent to Read, without deposit, for Six Months, CHARGE ONE PENNY.’ A clever ruse, which did not work.

Hetherington soon received a further summons but announced his intention to ignore it and left London. Despite the issue of an arrest warrant he carried on unmolested. Meanwhile, the Guardian continued its weekly appearances, noisily proclaiming that the government was deliberately attempting to keep the poorer classes ignorant through the device of the stamp duty. The newspaper was not edited by Hetherington; others took on that task while he toured the country addressing meetings, recruiting vendors, and setting up distribution networks.

Sellers flocked to Hetherington’s aid throughout the autumn of 1831 with the result that prison sentences ranging between three and six months were inflicted on many. The tactics used to get around the authorities were varied and ingenious. Copies were hidden inside clothing and dummy parcels were made up to be openly carried by those who were already suspected, inviting inspection and occupying officials while the real parcel was delivered by an individual unknown to the authorities.

Hetherington became well known for his exploits in avoiding capture (at one point he disguised himself as a Quaker) and these were widely reported, with him becoming a hero to his readers. At the height of its popularity, the Guardian sold around 15,000 copies per edition, with a readership several times that number and live readings (not everyone was literate, of course) spreading the word still further. Hetherington’s high profile made him one of the government’s main targets for prosecution. E.P. Thompson has pointed out that imprisonment as a radical publisher brought honour, not odium, and helped further publicise the cause.

Late in 1831, Hetherington’s mother fell ill. The Bow Street Runners learned of this and lay in wait. As he attempted to enter his mother’s dwelling, he was arrested (despite putting up a fight) and was taken to Coldbath Fields Gaol, Clerkenwell for six months. Upon his release, he recommenced his activities and was arrested once again. This cycle was repeated on a further occasion, but still the paper continued to appear.

On 17 June 1834, a special jury sitting at yet another trial acquitted him and declared The Poor Man’s Guardian a ‘strictly legal publication’. The newspaper, having achieved its objectives, ceased in 1835. Nearly 600 individuals had been convicted and imprisoned for selling it.

In 1840, Hetherington found himself in court again, this time charged with blasphemous libel for publishing Charles Haslam’s Letters to the Clergy of All Denominations. As usual, he defended himself but was convicted and served another four-month prison sentence.

On his release, Hetherington decided to expose what he regarded as the authorities’ hypocrisy. He had never been prosecuted for selling Shelley’s radical poem Queen Mab and suspected that this was because it was also sold by ‘respectable’ booksellers. To make his point, he purchased a copy from the publisher Edward Moxon and then brought a private prosecution against him. Hetherington won the case, but Moxon was never imprisoned because Hetherington did not request sentencing. However, he had made his point and blasphemy prosecutions against serious works of literature ceased.

Hetherington’s radicalism remained undiminished. He became active in the ‘moral force’ wing of the Chartist movement alongside William Lovett, opposing the likes of Feargus O’Connor who favoured ‘physical force’. He occupied several posts in Chartist organisations. At the same time, he continued in the bookselling and publishing trade, which was celebrated by radicals and freethinkers and which made martyrs of many.

Hetherington died of cholera on 24 August 1849, having refused medication in the belief that his teetotalism would protect him. Shortly before, he had produced what he called his ‘Last Will and Testament’ and left several copies with associates. Here is an edited version:

In the first place then – I calmly and deliberately declare that I do not believe in the popular notion of the existence of an Almighty, All-wise and Benevolent God – possessing intelligence, and conscious of his own operations; because these attributes involve such a mass of absurdities and contradictions, so much cruelty and injustice on His part to the poor and destitute portion of His creatures – that in my opinion, no rational, reflecting mind can, after disinterested investigation give credence to the existence of such a Being.

In the second place, I believe death to be an eternal sleep – that I shall never live again in this world, or another….

In the third place, I consider priestcraft and superstition the greatest obstacle to human improvement and happiness…

In the fourth place, I have considered that the only religion useful to man consists exclusively of the practice of morality, and in the mutual interchange of kind action…

In the fifth place… I wish my friends, therefore, to deposit my remains in unconsecrated ground, and trust they will allow no priest, no clergyman, of any denomination, to interfere in any way at my funeral.

As he lived, so he died.

Over a thousand attended the funeral at Kensal Green Cemetery, where George Jacob Holyoake delivered the graveside oration. White was worn and the hearse was covered with a silk banner proclaiming, ‘We ought to endeavour to leave the world better than we found it’. Kensal Green was already becoming the burial site of choice for freethinkers and radicals. This trend had been encouraged by W. D. Saull’s purchase of two pieces of unconsecrated ground in 1848 within its bounds for the remains of ‘family and friends’. Hetherington was the first such to be buried there and his name also features on the Cemetery’s Reformers’ Memorial, which was erected in 1885, along with more than seventy others.

Bibliographical note

There is no full-length biography of Henry Hetherington. Apart from more general historical works, such as Adrian Desmond’s Reign of the Beast mentioned above, and Joel Wiener’s The War of the Unstamped (1969), there is a 62-page booklet by Ambrose G. Barker, Henry Hetherington, 1792-1849, published by the Pioneer Press in 1938. Most interestingly, there is a substantial article by Brian Hetherington (possibly a descendant), ‘Henry Hetherington: “The Poor Man’s Guardian”’, which was published in The Literary Guide in August 1949 and upon which I have drawn extensively in the writing of this essay. There is a scattering of other articles, some in the Freethinker (check the digital archive), which have been intermittently published during moments when the heroic Henry Hetherington is briefly rediscovered…only to be forgotten again.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate