Introduction

The liberal, democratic, capitalist model of the West is arguably the most successful form of human government to date. Yet, its origins lie in a rich tradition of various political philosophies which considered democracy in many different forms. Our specific system evolved over centuries. It was not designed but grew out of a complex set of historical conditions. We now believe, however, that our current model is the only form that democracy, and modernity, can take.

Conceptions of Democracy

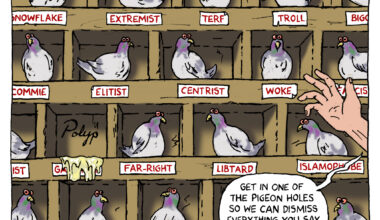

Professor Alan Ryan sets out in his On Politics: A History of Political Thought from Herodotus to the Present (2012) that there are distinctions between ‘theorists of democracy who think of democracy as a matter of the character of a whole society, extending far beyond its political machinery, and those who see democracy as a set of arrangements for answering the question “Who is to rule?”’ We now have the latter, with limited political democracy consisting of voting every four or five years for pre-selected candidates alongside ‘free’ markets and private property. To the modern mind, these are the hallmarks of modern democratic societies. This article argues in favour of the former view outlined by Ryan, the broader conception of democracy, expanded in the political sphere and introduced in the economic sphere.

The narrower conception of democracy is very much the status quo view in the West. It is firmly entrenched, and its superiority is taken as a given, as best represented by Francis Fukuyama, who put it thus: ‘[I]t is not necessary that all societies become successful liberal societies, merely that they end their ideological pretensions of representing different and higher forms of human society.’ Let us first examine the assumptions which undergird this worldview and why they are flawed.

The Free Market and Private Property

The economist Ha-Joon Chang wrote in the first chapter of his 2010 book 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism that: ‘Overcoming the myth that there is such a thing as an objectively defined “free market” is the first step towards understanding capitalism.’ What is free to be traded or sold results from a series of choices made by human beings depending on the political, moral, and economic thinking of the place and time. Up until the mid-19th century, the selling and purchasing of human beings was legal in the Southern United States. This slave economy enabled the US to become the premier exporter of cotton in the world. Four ports in the South accounted for 85% of US cotton exports to Britain. Although the British Empire had abolished the slave trade in 1807, it did not abolish slavery itself across the empire until 1833, and in the decades following, it still relied on slave-picked cotton for its mills. Human slavery was still in the ambit of the free market as it existed then, even if the market meant an inhuman imposition and unfree peoples.

The concentration of ownership in our system also undermines the complacent assumptions we have about the free market. A 2023 report by the Media Reform Coalition found that three companies (DMG Media, News UK, and Reach) own 90% of the UK’s national newspaper market. Meanwhile, at their peak, the Big Six (British Gas, EDF Energy, E.ON, npower, ScottishPower, and SSE) supplied energy to seven out of ten UK households.

One could make a modest plea for greater diversification of the market, which has occurred in recent years with the introduction of new players such as Octopus Energy and Utility Warehouse. But this is not enough, and the argument needs to be pushed further. The question should be: why have private companies been able to lay claim to the common stock of resources and sell it back to the public? This contradicts the common assumption of a free market where consumers are free to choose if they want something or not. Energy is not optional—we all need it—and by its privatisation we are compelled to pay the companies who own it. This is likewise true of our water and our train companies. In other words, the key elements of life are owned and managed by a small number of major corporations, investment firms, and high-net-worth individuals. The public is almost completely excluded from the process.

To therefore argue, without straining our definitions, that we live in free, democratic societies is to have an extremely narrow conception of what we mean by democracy. We are offered innumerable choices but what we are Free to Choose, as Milton and Rose Friedman’s famous 1980 book was titled, is largely trivial, and major decisions are outsourced to our political and financial elites, meaning the general citizenry lacks meaningful control over the foundations of the society we call our own.

Returning to Chang’s book for a moment, it is worth focusing on his ‘Thing 16’: We are not smart enough to leave things to the market. This was best illustrated by the 2008 financial crash, caused by actors and institutions within the financial system, primarily in the United States. It is worth quoting Chang at length on this point:

So many complex financial instruments were created that even financial experts themselves did not fully understand them… The top decision-makers of the financial firms certainly did not grasp much of what their businesses were doing. Nor could the regulatory authorities fully figure out what was going on… If we are going to avoid similar financial crises in the future we need to restrict severely freedom of action in the financial market.

He rounds off by saying (no doubt anticipating his critics): ‘There is nothing exceptional about proposing to ascertain the safety of financial products before they can be sold.’ Although this would undoubtedly be an intervention and a restriction of the market, its necessity—for the sake of global economic stability—is forcefully argued for by Chang.

Furthermore, the free market is often wrongly placed in opposition to the state, a framing which misunderstands that the market would not be possible without the government which makes and enforces ‘the rules of the game’, as Robert Reich has put it. As Dean Baker argues in his 2006 book The Conservative Nanny State, ‘The key flaw in the stance that most progressives have taken on economic issues is that they accepted a framing whereby conservatives are assumed to support market outcomes, while progressives want to rely on the government.’

This false dichotomy means political groupings line up behind either the ‘free’ market or the state. What is missed in the debate is the role of the rest of the population and the expanded conception of democracy outlined by Ryan. The Greek economist Yanis Varoufakis said it best when he argued that, ‘The question is how do you empower communities with the necessary capital, the necessary expertise, and leave them to their own devices… I think that is the future, the future is for…living neither under the thumb of the state nor under the thumb of corporate capital.’

Private property typically conjures up images of home owning and a domain of private life protected against the impositions of the state. It has been argued for centuries that such a state of affairs guarantees the liberty of the individual. If the theory rested on a false reality, however, what would the implications be? The British writer and researcher Guy Shrubsole documents that 65% of land in England is owned by the aristocracy, corporations, oligarchs, and city bankers. Another nearly 30% is either unaccounted for or under the control of the public sector, conservation charities, the crown and royal family, and the Church of England. The percentage of land in England owned by what we would consider ordinary homeowners, the very people upon whom the false assumption about the liberating power of private property rests, is 5%. Staggering as this may be, it has been true not just of our recent history but for centuries. The vast majority of land is owned by a small percentage of the population.

A research briefing published by the House of Commons Library in April 2024 shows how income inequality today (as measured by the Gini coefficient) is the highest it has been since at least the 1960s. This is set to worsen given the rise in the cost of living, and when housing costs are taken into account, the disparity in incomes becomes even greater.

Our economic consensus consists of the worldview outlined above: free markets, private property, and limited political democracy. This worldview has had no serious competitors in the West in the last 150 years, and since the Thatcher and Reagan revolutions of the 1980s, it has gone into overdrive. With the West’s triumph in the Cold War, it was cemented into the public mind that liberal, capitalist democracy was not only the best existing system but the only possible system. There was even an acronym to describe this view: TINA (there is no alternative). The acronym also became the title of a book written by the journalist Claire Berlinksi: a hagiographic account of Margaret Thatcher which took for granted that Britain was sliding into ‘socialism’ in the 1970s and needed Thatcher to save the country. Despite this, the mantra of TINA is false. A different kind of economy already exists, one with extraordinary unrealised potential.

The Solution: Meaningful Control

Cooperatives, companies which are owned and controlled by their members to meet their shared needs, are a cornerstone of the ‘democratic economy’, as a recent report into the subject terms it. There are 7,370 cooperatives across the UK, with an annual income of up to £42.7 billion. Co-operatives tend to be more resilient than other businesses. In their early years of trading compared to other businesses, 81.2% of cooperatives are still successful after five years, compared to 39.6% for traditional start-ups. Cooperatives have a rich and long history in the UK, dating back to the mid-19th century and the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society when weavers working in the cotton mills organised themselves to change the means by which they worked and lived. Although originating in the UK, cooperatives have since spread far and wide. The International Cooperative Alliance estimates the existence of roughly 3 million cooperatives worldwide, employing 10% of the world’s employed population. Alternative forms of economic organisation are therefore clearly possible, and on the strength of the evidence, highly desirable.

A contemporary example of the phenomenon of democratic organisation is the Mondragon Corporation in Spain, a democratically owned and managed enterprise. It is neither small in size nor scale, a criticism often made of alternative forms of economic arrangement. Mondragon has annual revenues of £9.1 billion, 70,000 employees, and is active in finance, retail, education, and industry.

The corporation has 10 principles, a few of which are worth highlighting. Principle 2 is ‘Democratic organisation’, which means ‘[a] one person, one vote system for election of the cooperative’s governing bodies and for deciding on the most important issues.’ Principle 3 is ‘Sovereignty of Labour’ whereby ‘[p]rofit is allocated on the basis of the work contributed by each member in order to achieve this profit.’ Principle 4 is ‘Instrumental and subordinated nature of capital’, meaning that although the role of capital is recognised as important, it does not take precedence over labour and does not have a vote.

These principles are a radical departure from our current forms of economic organisation. Taking them in reverse order, Principle 4 is an inversion of the status quo in which decisions are taken by the directors/C-suite of a company (or by shareholders if the company has gone public). Principle 3 is not reflected in our current system at all, as shown by the massive disparities between the salaries of executives and those of the lowest-paid workers. Finally, there is not even a pretence of the application of Principle 2 in our workplaces, where no major decision is made by workers or in consultation with them. What Mondragon represents should be an aspiration for our wider economy.

Finally, citizen-owned energy enterprises are another sphere in which economic democratisation has benefitted communities and contributed to sustainable development. There are up to 9,000 ‘civic energy communities’ across the European Union in which engagement is voluntary and consists of buying a cooperative share. As an article from the Clean Air Task Force notes: ‘Through the democratisation of energy, energy communities can alleviate energy poverty and protect vulnerable citizens.’ Greater participation means a greater sense of what people’s needs are and how to address them. This is in stark contrast to the detachment necessitated by most modern corporations, which are run in the interests of their executives or shareholders—people who ultimately have merely a share rather than a stake in the company’s future.

Conclusion

In our current systems of economic organisation, there exists an unequal distribution of private property, unaccountable corporations, and major disparities in income. These are not bugs in the system, but features, which emanate from an absence of economic democracy. This is not a state of affairs in which people exercise meaningful control over their lives, and our participation, where it is invited, is intermittent and superficial. Concentrations of wealth lead to concentrations of power: the two are inevitably connected. And so John Dewey’s remark that: ‘As long as politics is the shadow cast on society by big business, the attenuation of the shadow will not change the substance’ continues to ring true.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate