Fanaticism comes to Sindh

The mother of the slain Dr Shahnawaz Kunbhar is in shock, overwhelmed by the weight of her grief as she sits with her grandchildren. In September 2024, Kunbhar was allegedly killed by local police during a staged encounter in Sindhari, a small town in the Mirpur Khas district in Sindh province, around 230 kilometres from Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city. Initially, the police claimed that Kunbhar was killed accidentally. However, two subsequent investigations, one by senior police officials and one by the Human Rights Commission (HRC), revealed this assertion to be false and exposed Kunbhar’s death as an extrajudicial murder.

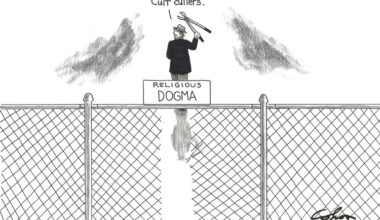

Days before his death, Kunbhar had been accused of blasphemy on social media by a cleric in Umerkot, where he worked in the local hospital, and a blasphemy case was opened against him (blasphemy is outlawed in Pakistan). The accusation had led to violent protests against Kunbhar in the days before his death. While blasphemy-related killings by mobs are common in Pakistan, police being the perpetrators is, or was, rare: a worrying development.

On Kunbhar’s mother’s right, her granddaughter Hareem Shah Nawaz weeps uncontrollably, while on her left, her grandson clutches a photo of his father, a heartbreaking reminder of their loss. She laments that no one truly understands the depth of a mother’s pain. Her son, a dedicated doctor who cherished her, was brutally murdered by the police, the very people who are meant to keep citizens safe. She appealed for justice, which emerged in the form of the investigations, the charging of suspects, and civil society protests and solidarity with Kunbhar’s family.

The extrajudicial killing of Kunbhar—which occurred not long after another blasphemy-related killing by a police officer in Quetta, Baluchistan—has shaken the entire province, instilling fear in those who cherish liberal, progressive, secular values and the right to free speech. Once Sindh was celebrated for its liberalism, secularism, and religious harmony. Now it seems to be engulfed by a surge of extremism and state-sanctioned violence based on mere allegations.

[I]ncidents like the killing of Kunbhar have left many deeply unsettled about the future of Sindh and its enduring spirit of harmony and tolerance.

Waves of religious extremism in Pakistan that arose during last century’s Afghan War and increased militancy in Kashmir passed over Sindh, but the region remained, on the whole, a bastion of peace and religious tolerance, perhaps owing to the dominance of Sufism there. Tragically, incidents like the killing of Kunbhar have left many deeply unsettled about the future of Sindh and its enduring spirit of harmony and tolerance. Prior to this, in 2019, Professor Notan Lal was accused of blasphemy and spent five years in prison before the Sindh High Court set his conviction aside.

Despite the police stating that Kunbhar’s death was the result of an accidental encounter, claims that Kunbhar had been extrajudicially murdered quickly went viral on social media and the investigations eventually showed that it was a staged encounter. Other posts, featuring local clerics congratulating the police on killing an insolent blasphemer, also went viral. In these images, police officers were smiling and wearing necklaces.

The tragedy did not end there. A mob blocked Kunbhar’s father from entering his village with his son’s body. When Kunbhar’s relatives took the body elsewhere, the mob followed, snatched the body, and set it ablaze. Clerics also declared that the traditional ritual prayers would not be allowed for Kunbhar. Out of fear, the family did not perform the rites. It was as if they had been abandoned in their time of need, while even the state authorities remained silent, suggesting complicity in, or at least tacit approval of, the murder.

Thankfully, civil society stepped in and came to the village to honour Kunbhar and his family. Activist Sindhoo Nawaz Ghanghro issued a call to action, referring to Kunbhar’s killers as Islamic extremists. She urged people to support the family and share in their pain over Kunbhar’s brutal killing. Her call broke the silence. Ghanghro, along with local singers, Sindhi nationalists, and other activists of various stripes, arrived at the village and held a ritual ceremony in his absence.

Sindhi folk/Sufi singers Manjhi Faqeer and Khushboo Laghari, among others, sang songs and performed the poetry of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai and other Sufi mystics at the grave, conveying a message of love for humanity amid a large crowd of people.

On 25 September 2024, a rally was held in Umerkot, a few kilometres away from Kunbhar’s native village, condemning the religious extremism and the killing of the doctor. Participants demanded the arrest of the culprits, including the police officials and local clerics responsible for Kunbhar’s death, and they vowed to stand behind the bereaved family and to protect Sindh’s identity, which is rooted in its history of religious harmony, come what may. During her address at the rally, Ghangro emphasised that Sindh is rooted in tolerance, love, and peace and that its people would lay down their lives to protect this identity.

The investigations into the incident were set up amid this mounting pressure and criticism on social media. The first investigation recommended taking action against the police officials involved, including several high-ranking ones, while the HRC investigation noted that several breaches occurred in Kunbhar’s case, including violations of the right to free speech, the right to a fair trial, and the right to security of life, all of which are guaranteed by the state. The HRC stated that the authorities had failed to perform their responsibilities in this case.

Ganghro issued a call for another march in Karachi on 13 October, prompting the Tehreek-e-Labaik Pakistan (TLP), a rising far-right Islamist extremist group in Pakistan, to announce a counter-protest in the same place on that date. Local authorities decided to prohibit both events to avoid clashes but both parties remained steadfast, with Ganghro declaring that ‘The march will take place no matter what’. And indeed, a large number of people, including many women, showed up on the appointed date.

In response, the police brutally treated the marchers, beating and arresting women, intellectuals, and human rights and political activists, including Ganghro. A young female lawyer, Romasa Chandio, who studied in the United Kingdom, sustained a foot fracture during the clashes at Karachi Press Club and was jailed for hours.

The rise of extremism in Pakistan

These events in Sindh are reflective of a sad reality to be found all across Pakistan: the rise of religious extremism. I spoke to Dr Riaz Hussain Sheikh, an award-winning professor and dean at Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology in Karachi, who told me that that religious organisations in Pakistan are often aligned with the establishment.

During the independence movement in Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan, such organisations supported Pakistani military operations and were involved in the killing of civilian Bengalis, playing a pro-dictatorship role and undermining elected governments in Pakistan, added Dr Sheikh.

Another instance of extremists backing dictatorship in Pakistan came in 1977 after the general election victory of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. The Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) was formed to oppose Bhutto and included various religious organisations such as the Islamist party Jamaat-e-Islami. Most of the members of the PNA allied themselves with General Zia-ul-Haq, who overthrew the democratically elected government and imposed martial law. In the years following, Zia used religion to buttress his authoritarian regime. According to research by Hashmat Ullah Khan, Jamal Shah, and Fida-Ur-Rahman,

It was Zia-ul-Haq who greatly radicalized the Pakistani society with the obvious aims to [sic] legitimatize his dictatorial rule. His rigid and dogmatic interpretation of Islam led to the birth of extremism, intellectual obscurantism and fundamentalism in Pakistani society.

We are still dealing with the consequences of Zia’s actions today, with religious extremism partnered with the establishment on the rise.

Dr Sheikh noted, for example, that the fundamentalist party Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, having gained influence across the Baluchistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces, has expanded into Sindh, establishing madrasas there. Dr Sheikh is worried by the rise of religious extremism and warns that if this trend continues, Sindh will face more violence and fanaticism in the future. However, the strong resistance in Sufi-dominated Sindh, with its belief in humanity, might act as a bulwark against such an outcome. Dr Sheikh notes that Dr Kunbhar hailed from the Thar Desert of Sindh, known for its peace and religious harmony. However, many madrasas currently operate in Thar, posing a danger to the future of Sindh.

According to research by the Centre for Research and Security Studies (CRSS), between 1947 and 2021, there were around 2,000 blasphemy accusations and cases in Pakistan, and blasphemy incidents greatly increased after the restoration of democratic government in 1988, says the CRSS: of 1,306 accusations recorded during the period, around 1,300 occurred between 1988 and 2021, with the worst years being 2012, 2014, and 2020.

[T]he people of Sindh are demanding an end to religious violence and fanaticism before it poisons their region.

Pakistan is predominantly Muslim, but in Sindh, especially the Thar area, religious communities have generally gotten along. Now, after the murder of Dr Kunbhar, the sense of safety and cooexistence has been shattered. I spoke to Bart Kumar, a teacher from Umerkot, who expressed deep concern that the murder of Kunbhar has left a lasting psychological scar on religious minorities. He noted that if a Muslim can be subjected to such violence, then those who belong to religious minorities—who already grapple with feelings of inferiority and face persecution—are only left with heightened anxiety and fear for their safety. He worries that this fear might drive religious minorities to migrate to India, forcing them to abandon their ancestral homeland, an outcome that he would deeply lament.

The future of Sindh and Pakistan

In Sindh, music and poetry are vital to Sufism and play a significant role in combating extremism. Historical and contemporary Sufi poets, Dr M Rafiq Wassan of the University of Jamshoro told me, contribute to harmony and unity.

Wassan, who earned his PhD researching the role of Sufism in Sindh, said that Sufi poetry promotes a mindset that transcends religious boundaries, fostering a Sufi culture that counters elitism and extremism, and that this is why Sindh is different to the rest of Pakistan. Tolerance and peacefulness are central tenets of Sufism, which is why Sindh is liberal and resistant to extremism, he added.

Religious extremism remains a significant concern in Pakistani society. Although the government has implemented policies against extremism, tangible results are lacking. The state’s lack of serious action and sluggishness in response to Dr Kunbhar’s murder highlights its present inability to counter extremism, as wrongful acts continue to be committed in the name of religion without effective intervention, Wassan said. Meanwhile, Dr Sheikh emphasised that when the state uses religion as a tool, the system inevitably collapses. Religious extremism poses a threat to democracy and human rights, as well as to global peace, he said.

This is why the people of Sindh are demanding an end to religious violence and fanaticism before it poisons their region. I remember the pain of Dr Kunbhar’s mother and children, and I hope that the spirit of Sindh prevails.

Related reading

The evils of feudalism in Pakistan: a personal and political narrative, by Malik Ramzan Isra

The Galileo of Pakistan? Interview with Professor Sher Ali, by Ehtesham Hassan

How the persecution of Ahmadis undermines democracy in Pakistan, by Ayaz Brohi

From the streets to social change: examining the evolution of Pakistan’s Aurat March, by Tehreem Azeem

Surviving Ramadan: An ex-Muslim’s journey in Pakistan’s religious landscape, by Azad

Coerced faith: the battle against forced conversions in Pakistan’s Dalit community, by Shaukat Korai

Breaking the silence: Pakistani ex-Muslims find a voice on social media, by Tehreem Azeem

From religious orthodoxy to free thought, by Tehreem Azeem

Religion and the decline of freethought in South Asia, by Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate