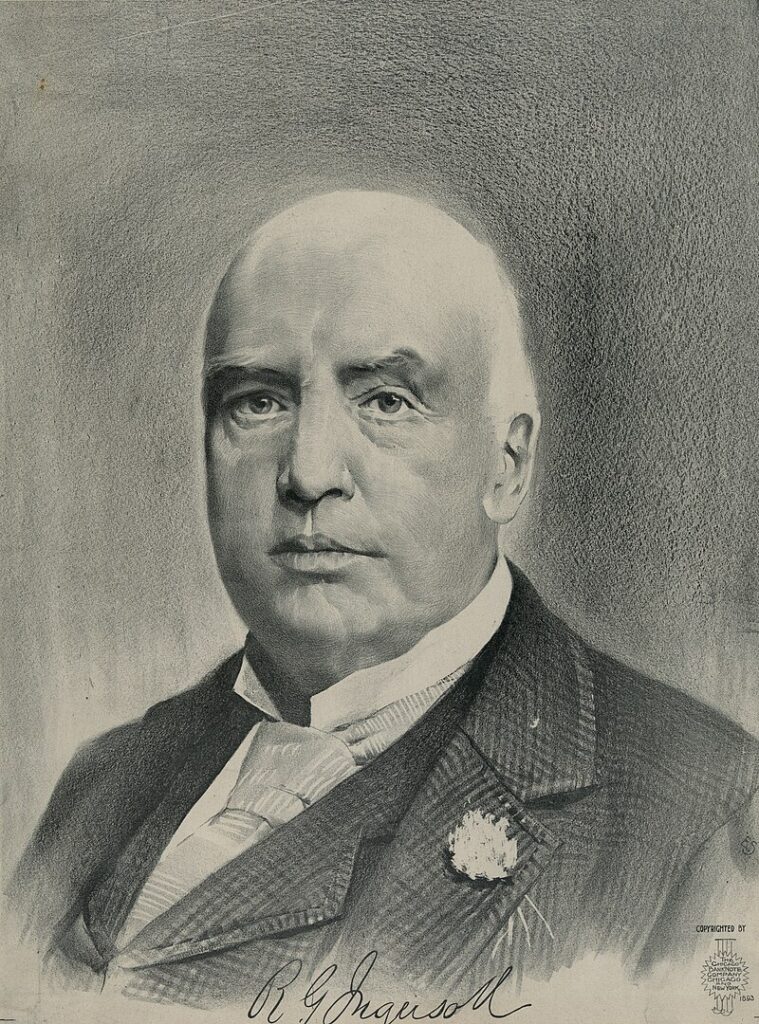

Robert Green Ingersoll is perhaps the greatest lost figure in freethought history. In an age before microphones and mass media, he was a household name in America—a thunderous voice for liberty, reason, and human dignity whose influence rivalled presidents and whose fame once surpassed that of the most celebrated authors and inventors of his time. Yet today, he is little known outside circles of historians and freethinkers.

Born in 1833, Ingersoll served with distinction in the Civil War as a colonel in the Union Army. But his true battlefield was the lecture hall and public stage. Over thirty years, he delivered more than 1,500 lectures across the country, speaking on topics from religion and politics to science, Shakespeare, and human rights. He often held audiences spellbound for four hours at a time—without notes—his voice booming before crowds as large as 50,000. Before the advent of radio and film, no one in American history had been seen and heard by more people.

Ingersoll’s admirers included many of the most celebrated figures of the 19th century. Mark Twain called him ‘a master of words’ and ‘one of the greatest men this country has ever produced.’ Thomas Edison remarked, ‘Ingersoll’s ideas were ahead of his time. He helped set mankind free.’ Walt Whitman praised him as ‘a man full of the western genius and audacity’, while Frederick Douglass said, ‘He stands among the great teachers of morality and truth.’ Oscar Wilde called him ‘the most intelligent man in America.’

At the heart of Ingersoll’s legacy was his belief in a morality grounded not in divine commands but in reason and human flourishing. ‘Happiness’, he said, ‘is the only good; the time to be happy is now, the place to be happy is here, the way to be happy is to make others so.’ He championed reason over superstition and was known as ‘The Great Agnostic’ for his outspoken critiques of religion. His most famous lectures—The Gods, Some Mistakes of Moses, and Why I Am an Agnostic—challenged dogma with wit, clarity, and compassion.

He also made it his mission to rescue the reputations of past freethinkers. His lectures celebrated figures like Voltaire, Shakespeare, and especially Thomas Paine, whose role in the American Revolution had been obscured by religious hostility. Ingersoll took it upon himself to restore Paine’s legacy, declaring that ‘without Thomas Paine the history of liberty cannot be written.’

Ingersoll was also an uncommon bridge builder. He counted as friends both industrialists like Andrew Carnegie and socialists like Eugene V. Debs, drawn together by mutual respect for Ingersoll’s honesty and moral courage. He was a fierce defender of women’s rights, advocating for suffrage and access to birth control decades before such ideas were mainstream. He supported the full equality of black Americans and welcomed all people into his home regardless of race—an almost radical stance in post-Civil War America.

Politically, he was a sought-after Republican stump speaker and friend to several presidents, including James Garfield and William McKinley. Ingersoll rightly praised the Lincoln-Republicans of his day as the party that ‘took the chains from four millions of people’ and ‘put down the Rebellion.’ Ingersoll stood for liberty in every human sphere—intellectual, personal, spiritual, and economic. It is precisely this consistency that has led to his neglect: modern ‘liberals’ ignore him for his support of capitalism and constitutionalism, and conservatives for his atheism and secularism.

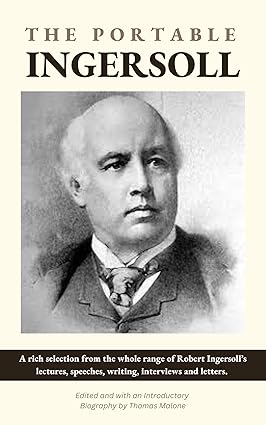

His present obscurity is a tragedy. Ingersoll’s powerful voice of reason is needed today in our ‘woke’ age of secular and religious irrationalism. In The Portable Robert Ingersoll, I’ve carefully curated the ‘best of the best’ of his lectures, showcasing the full range of his thought across religion, politics, art, science, and literature. This anthology isn’t just his best; it’s my case for why he matters today. In a time of rising authoritarianism and political tribalism, Ingersoll’s defence of ‘the liberty of hand and brain’ is more relevant than ever.

In addition to his courage, brilliance, and powerful logic, Ingersoll had three other attributes that endeared him to believers and freethinkers: wit, compassion, and eloquence. A few excerpts from The Portable Ingersoll will help demonstrate these unique aspects.

Ingersoll’s wit sparkled through his clever analogies and sharp satire, dismantling dogma with humour that delighted Gilded Age audiences and still resonates with freethought readers today:

Each nation has created a deity to suit its own needs and then claimed it was the other way around. The Greeks had their gods of war and wine, the Egyptians their cats and crocodiles, and the Hebrews their jealous Jehovah, who loved to smell the smoke of burning flesh. If these gods exist, they must have a good laugh at the expense of their worshippers! Imagine a deity who demands constant adoration and yet makes such a mess of the world. I’d rather trust a good blacksmith to run the universe—he’d at least know how to fix a broken wheel without flooding the earth! [Laughter noted in audience records.]

His quips targeted politicians as well. At the National Theatre in 1884, Ingersoll delivered his ‘Orthodoxy’ speech to a packed house that included dozens of congressmen, saying: ‘They often pray for the impossible. In the House of Representatives in Washington I once heard a chaplain pray for what he must have known was impossible: “I pray thee, O God, to give Congress wisdom.”’

One contemporary said Ingersoll was as ‘sentimental as an old violin’, and this endearing quality can be seen in his short essay called ‘Love’:

Love is the only bow on Life’s dark cloud. It is the morning and the evening star. It shines upon the babe, and sheds its radiance on the quiet tomb. It is the mother of art, inspirer of poet, patriot and philosopher. It is the air and light of every heart – builder of every home, kindler of every fire on every hearth. It was the first to dream of immortality. It fills the world with melody – for music is the voice of love. Love is the magician, the enchanter, that changes worthless things to Joy, and makes royal kings and queens of common clay. It is the perfume of that wondrous flower, the heart, and without that sacred passion, that divine swoon, we are less than beasts; but with it, earth is heaven, and we are gods.

Ingersoll’s eloquence, rivalling his hero Shakespeare’s lyrical grandeur, captivated audiences. Mark Twain (who knew a thing or two about words himself) said Ingersoll’s words ‘will sing through my memory always as the divinest that ever enchanted my ears.’ For a taste of what he was referring to, consider Ingersoll’s description of ‘The Real Bible’:

The real Bible is not the work of inspired men, or prophets, or apostles, or evangelists, or of Christs. Every man who finds a fact, adds, as it were, a word to this great book. It is not attested by prophecy, by miracles, or signs. It makes no appeal to faith, to ignorance, to credulity or fear. It has no punishment for unbelief, and no reward for hypocrisy. It appeals to man in the name of demonstration. It has nothing to conceal. It has no fear of being read, of being contradicted, of being investigated and understood. It does not pretend to be holy, or sacred; it simply claims to be true. It challenges the scrutiny of all, and implores every reader to verify every line for himself. It is incapable of being blasphemed. This book appeals to all the surroundings of man. Each thing that exists testifies to its perfection. The earth, with its heart of fire and crowns of snow; with its forests and plains, its rocks and seas; with its every wave and cloud; with its every leaf and bud and flower, confirms its every word, and the solemn stars, shining in the infinite abysses, are the eternal witnesses of its truth. For thousands of years men have been writing the real Bible, and it is being written from day to day, and it will never be finished while man has life. All the facts that we know, all the truly recorded events, all the discoveries and inventions, all the wonderful machines whose wheels and levers seem to think, all the poems, crystals from the brain, flowers from the heart, all the songs of love and joy, of smiles and tears, the great dramas of Imagination’s world, the wondrous paintings, miracles of form and color, of light and shade, the marvelous marbles that seem to live and breathe, the secrets told by rock and star, by dust and flower, by rain and snow, by frost and flame, by winding stream and desert sand, by mountain range and billowed sea. All the wisdom that lengthens and ennobles life – all that avoids or cures disease, or conquers pain – all just and perfect laws and rules that guide and shape our lives, all thoughts that feed the flames of love, the music that transfigures, enraptures and enthralls, the victories of heart and brain, the miracles that hands have wrought, the deft and cunning hands of those who worked for wife and child, the histories of noble deeds, of brave and useful men, of faithful loving wives, of quenchless mother-love, of conflicts for the right, of sufferings for the truth, of all the best that all the men and women of the world have said and thought and done through all the years. These treasures of the heart and brain – these are the Sacred Scriptures of the human race.

Robert Ingersoll lived as a beacon of freedom—mentally, morally, and spiritually unbound, a hero of the Golden Age of Freethought. Though his voice has faded from public memory, his words still resonate with the enduring power of truth and the bright promise of liberty, inspiring minds to embrace reason, oppose dogma, and pursue happiness without fear.

This article is based on Tom Malone’s forthcoming anthology, The Portable Robert Ingersoll, to be released on 5 May 2025. For more information on Tom’s writing and activities, please visit https://tjmalone.com.

Related reading

Freethought History Webinar #3: A Paine Party? Thomas Paine’s Relevance in America’s Gilded Age—and Today. With Dermot Trainor (27 May) (In which Ingersoll, Twain, Whitman, and others are due to be discussed.)

Freethought and birth control: the untold story of a Victorian book depot, by Bob Forder

American democracy will soon turn 250. Freethought can reinvigorate it. By Patrick Seamus McGhee

The radical atheism of the American revolutions: interview with Matthew Stewart, by Daniel James Sharp

The rhythm of Tom Paine’s bones, by Eoin Carter

Do we need God to defend civilisation? by Adam Wakeling

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate