Books From Bob’s Library is a semi-regular series in which freethought book collector and National Secular Society historian Bob Forder delves into his extensive collection and shares stories and photos with readers of the Freethinker. You can find Bob’s introduction to and first instalment in the series here and other instalments here.

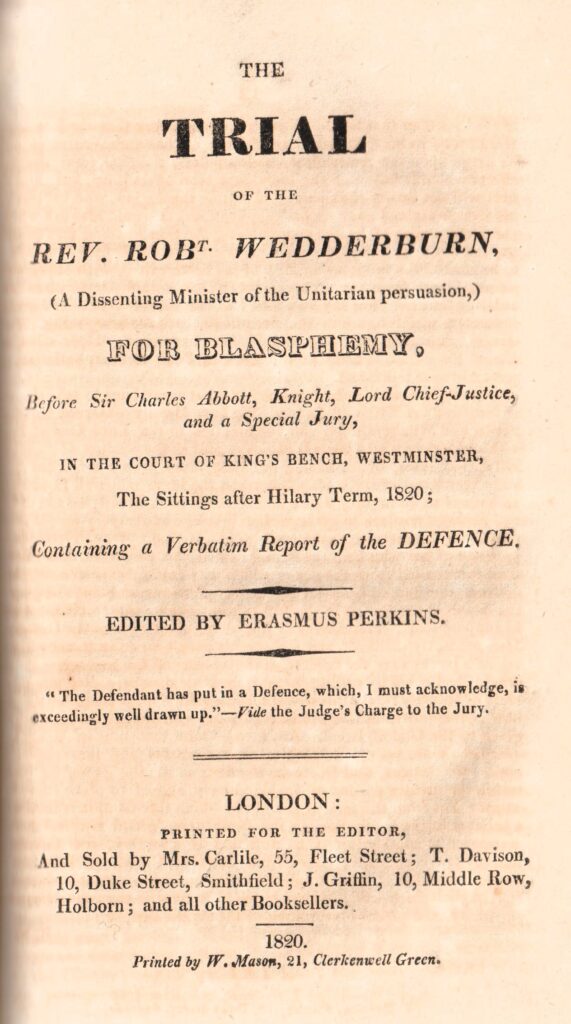

Recently, I was delighted to acquire a sammelband (a collection of pamphlets bound into a volume) comprising around fifteen separate publications. Treasures within include Richard Carlile’s Life of Thomas Paine; a record of Carlile’s 1819 trial leading to his incarceration at Dorchester; and several issues of The Deists’ Magazine. However, perhaps best of all is the record of Robert Wedderburn’s trial of 1820.

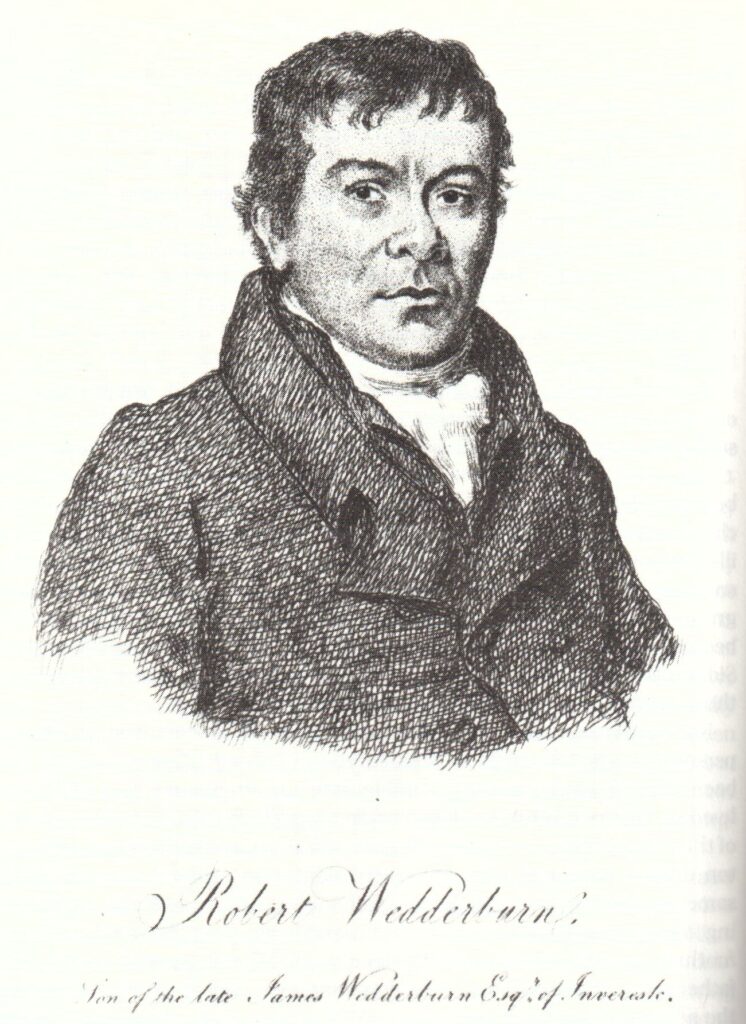

Throughout its 144-year history, the Freethinker has published articles on some of the outstanding historical figures who have bravely represented the freethinking intellectual tradition. It seems strange that the name of Robert Wedderburn has been virtually entirely ignored. Having searched the Freethinker archive, I can find only one very brief mention of him, in the issue of 26 May, 1940. This is an odd circumstance, and one I shall return to. Here it suffices to say that Wedderburn was one of the most extraordinary, courageous, and outrageous figures deserving of recognition as a freethought pioneer, despite what many would regard as grievous blots on his character and career.

Robert Wedderburn was born in Jamaica in 1762, the son of an African-born slave named Rosanna. His father was a Scot, James Wedderburn—a doctor and slave and sugar plantation owner. Rosanna had, in Wedderburn’s words, a ‘rebellious and violent temper’, leading to at least one flogging and eventually resulting in her sale and separation from her infant son, although he and his older brother were registered free at birth at their father’s insistence. Wedderburn was adopted by his maternal grandmother, ‘Talkee Amy’. His formal education finished at the age of five and he remained near illiterate all his life, learning to live off his wits without regard to the law. Amy’s loquacity probably contributed to Robert’s talent for oratory.

To escape Jamaica, he joined the Royal Navy at Kingston, aged 16, and saw action as a gunner against the French and Spanish. On leaving the Navy, many found themselves cheated of promised payments; this may have contributed to his rebelliousness.

Aged 17 he left the Navy and drifted to the rookeries (the very worst slums) around St Giles, London, and may well have become part of a subculture of ‘blackbirds’ who made their living partly as thieves, although Wedderburn worked as a tailor and may have served some sort of apprenticeship in Jamaica. However, he never gained guild recognition and would have suffered competition from the legion of unqualified ‘dung’ tailors. In his groundbreaking and scholarly 1988 book Radical Underworld: Prophets, Revolutionaries and Pornographers in London, 1795-1840, Iain McCalman claims that Wedderburn ‘was to drink, steal, blaspheme, brawl, work for a pornographic publisher and open a bawdy house’. He faced at least one spell in Coldbath Fields Gaol.

Wedderburn’s religious development was equally tempestuous. In 1786 he claimed conversion to Methodism, perhaps due to Methodism’s association with the anti-slavery movement (indeed, much later in life Wedderburn published The Horrors of Slavery, which had a significant influence on the abolitionist movement). However, his radicalism became increasingly pronounced. He claimed that English liberty was a myth, with priests, aristocrats, and kings having a stranglehold on political power, and he demanded that prisons be abolished and that capital punishment and flogging be ended.

By 1810 he was claiming to be a Unitarian. Having evolved from Anglicanism through Methodism and Unitarianism, he developed a freethinking, individualistic radicalism. He came to see revealed religion as a mechanism of social control designed to underpin the existing social and political hierarchy. In this respect Wedderburn had something in common with establishment views, like those of William Wilberforce, that ‘irreligious propaganda’ undermined the ‘social edifice’. Where Wedderburn and the likes of Wilberforce differed was in their view as to whether this was desirable.

One further influence on Wedderburn was the radical political teachings of Thomas Spence, which can be seen in Wedderburn’s short-lived 1817 periodical The Axe Laid to the Root. Here, Wedderburn made a series of proposals drawn from his experiences of slavery and as a degraded artisan, Methodist, and thief.

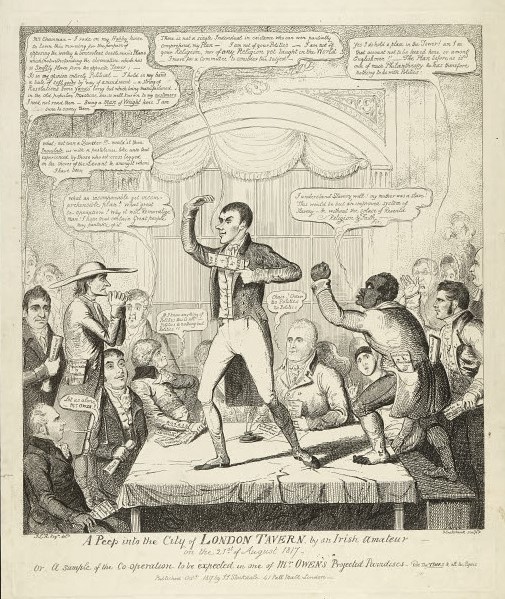

On 23 April 1818 Wedderburn opened his Unitarian meeting house, the Hopkins Street Chapel. The main room, ‘a ruinous hay loft’ with a capacity of around 300, was reached by a stepladder. Tickets cost a shilling and admitted the bearer to twice-nightly debates and a Sunday afternoon lecture for a month. Allen Davenport, himself a radical, said of Wedderburn that ‘…he studies politics all day, writes on politics, dreams politics and stands here twice weekly preaching blasphemy and sedition.’ (Quoted in McCalman’s Radical Underworld.)

Inevitably, Wedderburn attracted the attention of government spies, to whom contemporary historians are grateful for their reports. In Radical Underworld, McCalman gives an evocative account of Wedderburn in harness:

His coarse and profane language; his colour and physique (often described as stout); and the spectacular events of his life – the slave background, rejection by his wealthy family, experiences as a fighting sailor, criminal and pauper – were, to say the least, arresting. He displayed the traits characteristic of many populist leaders – physical bulk, roguery, flamboyance, bombast, emotional religiosity and thirst for martyrdom.

The Peterloo Massacre of 16 August 1819 represents a watershed moment in British radical history. Increasingly there was talk of physical force being used to counter state repression. Peterloo fired the militants, of which Wedderburn was one, into advocating ‘revolution’ and the acquisition of weapons. Many radicals began to champion weapons training and the practicing of drilling and manoeuvres for the people. One Hopkins Street debate featuring Wedderburn carried the title ‘Is it any sin to kill a tyrant?’ McCalman goes so far as to claim that if he hadn’t been in prison at the time, Wedderburn would have joined Arthur Thistlewood, who he knew well, in the foiled Cato Street Conspiracy to assassinate leading members of the government. Thistlewood and four others were executed following the plot’s collapse.1

My 24-page copy of the record of Wedderburn’s trial of 25 February 1820 for blasphemous libel was edited by Erasmus Perkins, an alias for George Cannon. Cannon himself was a fascinating character: a solicitor, radical activist, publisher, and pornographer. The pamphlet was sold by ‘Mrs Carlile’, i.e. Jane Carlile, Richard’s wife, who had taken over his publishing and bookselling business while he was serving his sentence in Dorchester Gaol. (For more on Peterloo and the Carliles, see my Books from Bob’s Library #3: Richard Carlile’s ‘The Republican’ and ‘Every Woman’s Book’.)

The prosecution’s evidence relied upon the testimony of two Home Office spies, William Plush and Mathew Mathewson, who had attended the Hopkins Street Chapel. The account of the trial notes how the two witnesses’ accounts ‘harmonized remarkably’. They reported some of Wedderburn’s words:

Jesus Christ says “No man hath ever seen God,” then what a d—d old liar Moses must have been for he tells us he could run about and see God in every bush. Christ says, no man has conversed with God, and yet Moses had a long conversation with him; thus, one or the other must be liars.

When called upon, Wedderburn defended himself and began by describing his background and religious journey. He then went on to ask that the bulk of his evidence be read by the clerk on his behalf. The document had been dictated by Wedderburn, likely because he remained semi-literate throughout his life, and this was the technique he used when ‘writing’ pamphlets and periodicals. The nub of his case came towards the end of the document where he quotes Grotius and questions the very concept of blasphemy law:

…to put men in prison on account of their religious belief or persuasion, is a great oppression, and properly speaking, FALSE IMPRISONMENT…Can anything be more wicked?

The presiding Lord Chief Justice praised Wedderburn’s defence as ‘exceedingly well drawn up’ but noted that no witnesses were provided to challenge the prosecution’s statements, and it even appeared that their truth was accepted. The jury retired for around 45 minutes and returned to announce a guilty verdict but recommended mercy on the grounds that the defendant had lacked the ‘benefit of parental care.’ The judge regarded this lightly and sentenced Wedderburn to two years’ imprisonment.

Wedderburn was taken to Dorchester Gaol, remote from the political unrest of London, in the days before railways. This was no coincidence. A fellow inmate was none other than Richard Carlile, although their circumstances were very different. Carlile occupied a relatively commodious cell, large enough for both his wife Jane and sister Mary-Anne to join him when they were imprisoned for carrying on his publishing and bookselling work in London. Jane gave birth to a daughter during her imprisonment and Richard continued to edit his journal The Republican. The Carliles benefitted from sponsors, particularly Julian Hibbert, allowing them to purchase better accommodation, food, and other privileges.

Wedderburn, on the other hand, occupied a tiny, dingy, damp cell and was kept in solitary confinement. It seems unlikely that he and Carlile met while in prison. Michael Laccohee Bush suggests they had much in common, with both disputing the authority of monarchs, priests, and religious authority in any form. It seems to me it is therefore appropriate to class both as freethinkers, though there are important distinctions between them. While accepting the existence of Christ, Wedderburn denied his divinity, regarding him as a radical reformer (despite calling him ‘a bloody fool’ for turning the other cheek—a remark that was part of the blasphemy case against Wedderburn). But unlike the declared atheist Carlile, Wedderburn professed himself a Christian and did not reject an interventionist God, thus justifying prayer. (See Bush’s 2016 study The Friends and Following of Richard Carlile: A Study of Infidel Republicanism in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain.)

In the years after his release from Dorchester Gaol, Wedderburn opened a ‘New Assembly Room’ at 12 White’s Alley, Chancery Lane. However, this failed to rival the popularity of Hopkins Street. In Radical Underworld, McCalman argues that times were changing, and that Wedderburn’s ‘vulgar blasphemy’ and ‘indecency’ failed to appeal to artisan radical circles who sought a level of respectability. Wedderburn’s new venture closed in 1828 and was followed by his imprisonment for two years with hard labour in 1830 for operating a ‘bawdy house’ (brothel).

The date and circumstances of Robert Wedderburn’s death are unknown, but he may be the ‘Robert Wedderborn’ who died in Bethnal Green and was buried in a non-conformist ceremony on 4 January 1835.

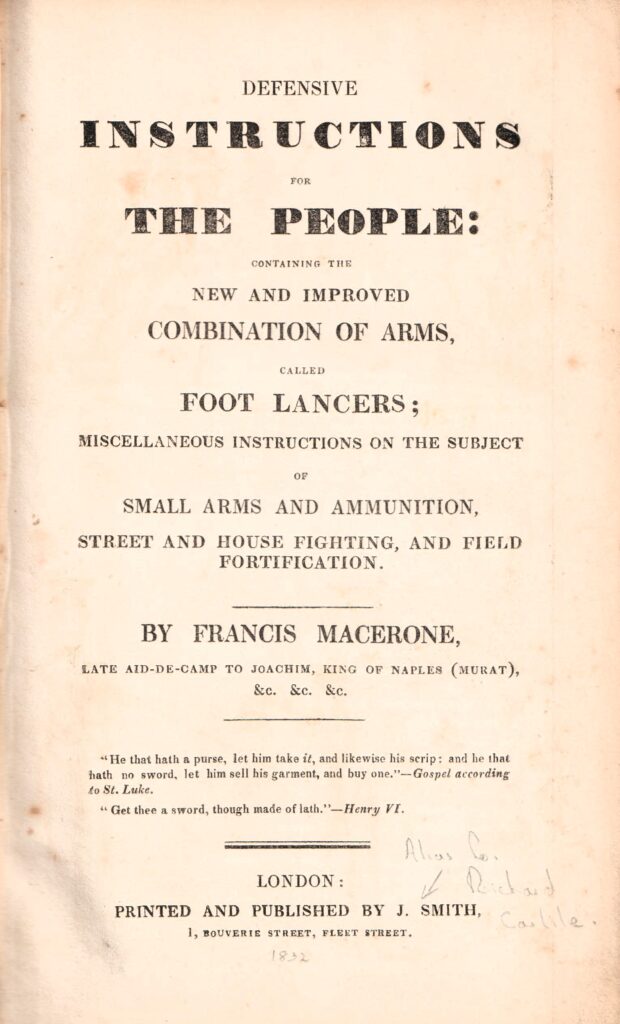

At the start of this essay, I asked why Wedderburn has received so little attention from freethinkers, and the Freethinker in particular. To an extent, this is reflected in the paucity of coverage by historians of radical history. G.W. Foote and Chapman Cohen edited the Freethinker for its first 70 years. They aimed to promote infidel ideas with a degree of intellectual gravitas. They also both sought to maintain the reputation of both the National Secular Society and the Freethinker and may have regarded Wedderburn’s memory as inimical to this. On occasions, Wedderburn advocated violence, and even murder, as legitimate in the struggle. Such views were not exclusive to Wedderburn, however. Carlile also wrote of the need for working people to defend themselves—and have the means to do so.

Does Wedderburn deserve credit for advancing the causes of freethought and secularism? I think he certainly does, because he was among the bravest of those who surrendered their liberty pursuing the cause of free speech, identifying religious authority and blasphemy law as central issues in the fight for freedom. He also understood how religion was used by political authorities as a means of social control in the interests of the privileged at the expense of their subjects. Last, but by no means least, he is an embodiment of the resilience of the human spirit. His example shows that no matter how repressive a state of affairs becomes, there will always be some who are willing to challenge arbitrary authority and injustice regardless of the consequences for themselves.

With thanks to Michael Bush for his observations and suggestions.

- The issue of the advocacy of violence by early nineteenth century freethinkers and republicans is rarely discussed, perhaps because those who write about them would prefer to avoid the issue. However, faced by provocation and armed force from the authorities, of which the best known, but no means only example, was Peterloo, some, including Wedderburn and Richard Carlile, came to advocate arming and preparing civilians for armed conflict. In 1832 Carlile published Francis Maceroni’s Defensive Instructions for the People under the alias J. Smith; this book provided detailed instructions on the design and use of lances. The next year, men with Maceroni lances turned up at the National Union of Working Classes’ meeting at Coldbath Fields, where they were used to fend off charging police, resulting in the death of one policeman. ↩︎

1 comment

Thanks for this marvellous introduction to Wedderburn – other readers might be interested to know that his first biography was published this year by Ryan Hanley. It interesting to consider Wedderburn’s advoacy of violence alongside that of Daniel Chatterton later in the century, who has also been neglected by chroniclers of freethought, perhaps for similar reasons.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate