Andrew Whitehead provides an update on Bradlaugh Hall in Lahore, Pakistan, and the ambition of some architecture students to rescue it. This follows an earlier piece he wrote about the Hall and broadcast on BBC radio in February 2020.

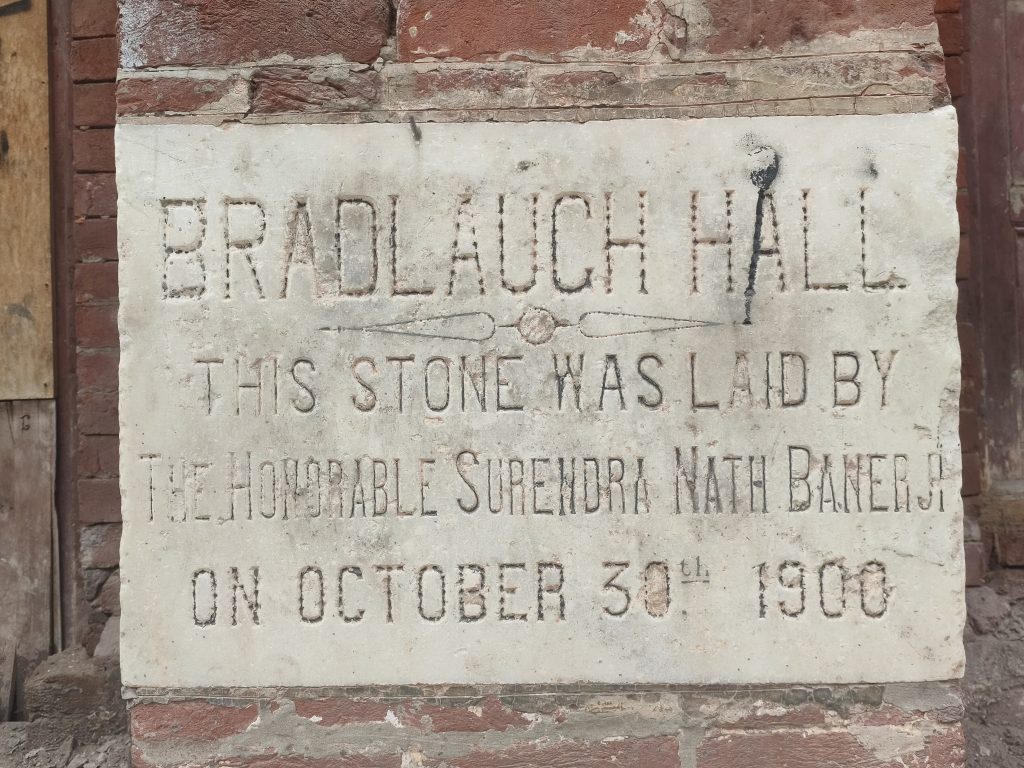

The most imposing building in the world to have taken Charles Bradlaugh’s name is in a city he never visited and in a country which did not exist in his lifetime. The construction of Bradlaugh Hall in Lahore began in 1900, nine years after the death of the man after whom it was named. For decades, it was a rallying point for the nationalist movement which brought an end to the British Raj. It is now dilapidated, and squatters have moved in. If nothing is done, it will simply crumble away. But among those who seek to conserve the city’s heritage, there are signs of interest in reclaiming and restoring this huge, architecturally heterodox building which is such an important part of Lahore’s history. A new generation of Pakistani architects is taking the lead.

Hiba Hamid Hashmi is an architect, urban designer and lecturer at the Lahore campus of COMSATS University (‘Commission on Science and Technology for Sustainable Development in the South’). She has given her students the task of devising an ‘adaptive reuse’ of the hall. ‘We are running this as a student project with an intention to revive the Hall as a public gathering space by introducing programmes inviting community activities,’ she says. ‘We also intend to propose a design strategy for the public square outside, as there is a dearth of public spaces in Lahore.’ One of her fourth-year students, Mohammad Moiz Khan, took the photographs which accompany this article.

From a humble household in Hoxton, Charles Bradlaugh quickly rose to become the commanding figure in the Victorian freethought movement. He was a prolific campaigner on the controversial issues of the day: a radical, republican, atheist, supporter of Indian and Irish nationalism, advocate of birth control, propagandist, pamphleteer and orator. He founded the National Secular Society in 1866 and established the National Reformer as one of the most widely read political journals of the day.

In 1880, Bradlaugh was elected MP for Northampton, standing as a Liberal but very much on the party’s radical wing. However, he was only able to take his seat in 1886, after a titanic struggle against opponents in Parliament who insisted that, as an atheist, he could neither affirm nor swear the oath of allegiance to the monarch on the Bible. He was a constitutionalist, a reformer rather than a revolutionary, and relished being in the House of Commons. He became a champion of Indian issues, protesting against the misuse of funds allocated for famine relief and the British authorities’ deposition of the Maharajah of Kashmir; this earned him the informal title of ‘Member for India’. His purpose was not to promote the British Raj but to seek to represent the interests of the Indian people in the imperial Parliament, since Indians themselves, as subjects of the Empire, had no formal representation.

Charles Bradlaugh set sail for Bombay (now Mumbai) on his only visit to India in November 1889, arriving there on Christmas Eve. He had been invited to address the recently established Indian National Congress. This later became the party of Nehru and Gandhi, but at the time consisted of an elite alliance of a small number of progressive Britishers in India and of politically assertive Indian lawyers and professionals. It had not yet reached the stage of demanding independence, but instead advocated for a much greater role for Indians in managing their own affairs.

The ‘Member for India’ was fêted. Five days after his arrival, his speech to the annual session of Congress was enthusiastically received. The text was later included in a volume commemorating the centenary of his birth (Champion of Liberty: Charles Bradlaugh, Freethought Press Association, 1933). ‘Friends, fellow-subjects and fellow-citizens,’ Bradlaugh began, to loud cheers, and went on:

‘I have no right to offer advice to you, but if I had, and if I dared, I would say to you men from lands almost as separate, although within your own continent, as England is from you – I would say to you men with race traditions, caste views, and religious differences – that in an empire like ours what we should seek and have is equality before the law for all – (cheers) – equality of opportunity for all, equality of expression for all – penalty on none, favouritism for none. And I believe in this great Congress I see the germs of that which may be as fruitful for good as the most fruitful tree that grows under your sun.’

He commended Congress for including women in its ranks, asserting that ‘great thoughts and great endeavours are not made less because the man goes to the woman for counsel in the hour of need, and makes the woman stronger.’

Bradlaugh made the trip out both to demonstrate his support for Indian nationalism and as a rest cure. He had been seriously ill and a long sea journey was seen as an enforced respite from his punishing, self-imposed workload. ‘My health is coming back very fast,’ he wrote in a voyager’s log which he kept while on board ship. He was deluding himself. While in India, Bradlaugh was not well enough to venture beyond Bombay. In early January he set sail for home. A year after his return to England, he died. M.K. Gandhi, then 21, was among the mourners who attended his funeral.

In 1893, the annual gathering of the Indian National Congress was convened in Lahore, the capital of the province of Punjab in British India. The session was presided over by Dadabhai Naoroji, a wealthy Bombay Parsee who in the previous year had become the first Indian to be elected an MP. His constituency of Central Finsbury adjoined Bradlaugh’s old meeting place at the Hall of Science on Old Street, and Naoroji took on Bradlaugh’s mantle of Member for India. It seems to have been at that session of Congress that plans were developed to build a hall in Lahore which would both honour Charles Bradlaugh and provide a venue for nationalists to assemble without requiring permission from the British authorities.

Fundraising for the hall in Lahore took some time; the foundation stone was only laid in October 1900. Over the decades, Bradlaugh Hall was used as a cultural and theatrical venue. Its political purpose was also amply fulfilled: in the first half of the twentieth century, just about every nationalist leader of note addressed rallies there. One of the most influential nationalists, Lala Lajpat Rai, set up a college within the Hall’s precincts.

In August 1947 the British withdrew from India. The Hall got caught up in the trauma of Partition, since Lahore lay inside Pakistan, though only a few miles from the dividing line. Much of Punjab erupted in violence, and the great majority of Lahore’s Hindu and Sikh communities fled from their home city and eastwards to India. In its way, the Hall, too, was a victim of Partition. In Pakistan, an Evacuee Trust Property Board was set up to administer the public buildings, particularly schools and places of worship, left behind by those who had migrated. It seems the managers of the Hall were among those who left Lahore, so the building became part of the Board’s extensive property portfolio. For a while, it was leased to an educational institute, but little attention was given to its upkeep.

Bradlaugh Hall is wonderfully located, close to the historic heart of Lahore. But it does not directly front a main road, so for many citizens of Lahore, it has long been out of sight and out of mind. Although the building is supposedly sealed shut, two years ago, I managed, with the help of a local historian, to get access to it, by clambering through an unlocked rear door. When I visited, the Hall was an austere, hollowed-out shell. It was evocative to stand where so many nationalist leaders would once have stood and delivered an uncompromising message about the injustice of British rule. There must be scope to reclaim this splendid building, so central to Punjab’s politics.

A campaign to Save Bradlaugh Hall, spearheaded by historians, heritage enthusiasts and civic activists, has been putting pressure on the local authorities to find a new purpose for this historic building. They want to see its renaissance as a cultural venue. Some money is said to have been allocated for basic repairs, but it is still not clear when, or whether, this work will take place. The future of the building is complicated by the mesh of different trusts and authorities whose support and funds are needed for the building to be reborn. Hashmi remains upbeat, encouraged by the enthusiasm of her architecture students. “Maybe when Lahore’s Walled City Authority actually manages to conserve the building, our faculty and students can pitch their ideas,” she says. “We hope for the best!”

Update, 16th May 2022

The Walled City of Lahore Authority (WCLA) and the Evacuee Trust Property Board have agreed on a Memorandum of Understanding to provide funding to restore the Hall. Further information here.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate