May is Humanism Month at the Freethinker. We will be exploring different conceptions of humanism, past and present.

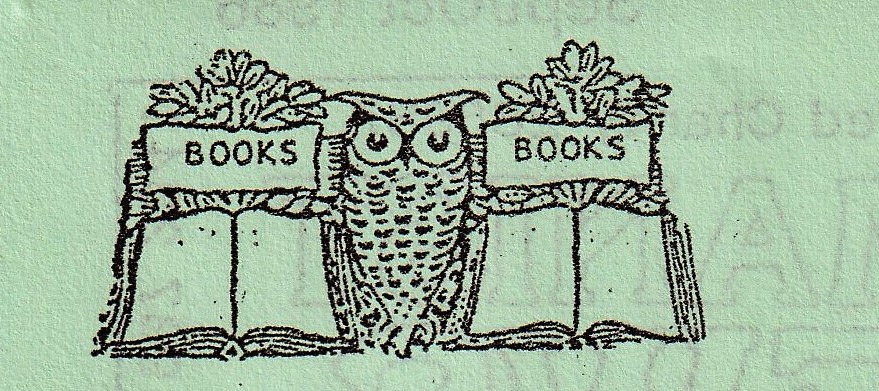

In 1986, the literary scholar Ian MacKillop published The British Ethical Societies, a history of the organisations that were founded in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the course of the Ethical Movement, with a view to exploring how to live morally without religion.

The below review was published in the September-October 1986 issue of Humanist News, at the time the newsletter of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK). Stanton Coit, mentioned in the review, became minister of South Place Religious Society (now Conway Hall) on condition that it became an Ethical Society instead. The Ethical Movement also led to the formation of the Union of Ethical Societies, the ancestor of HUK, in 1896.

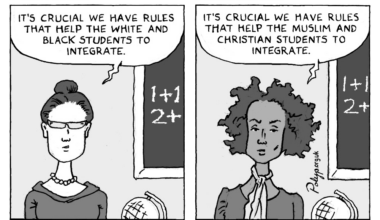

The Freethinker was intrigued to see the sort of people who, according to the unidentified reviewer, were attracted to the ethical societies back in their zealous, ‘militantly anti-individualistic’ early days.

In the reviewer’s words: ‘Ethics in its day, like ecology more recently, has a fashionable ring. It was a trend term for progressives, those people with an agonisingly efficient concience [sic] drawn in from the fringes of Positivism, Unitarianism, Socialism…The ethical societies were heroically tolerant of all shades of opinion, so long as it was contrary.’

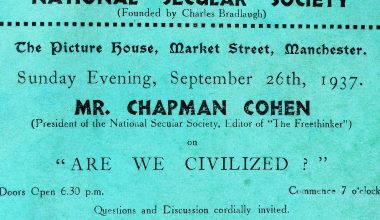

We are grateful to Bob Forder for submitting this image. Full text is copied out below.

Possessed by Not-Quite-Holy Spirit

Transcript as written.

This small and learned book, somewhat unpromising in title, turns out to be that rarest thing: an academic study that in its concentration on a new specific subject revives quite magically the whole feeling of a period. In tackling the ethicists, the network of societies dedicated to irreligious religion, the book of Hymns and Anthems with Hymns of Modern Thought, Dr. MacKillop has rekindled a good deal of the old ardour, the rationalist fervour, of the Time of the New Life, which was at it’s most exciting from 1890–1910 or so.

Ethics in its day, like ecology more recently, has a fashionable ring. It was a trend term for progressives, those people with an agonizingly efficient concience drawn in from the fringes of Positivism, Unitarianism, Socialism, Ramsey Macdonald was an anethicist for instance, though perhaps not a typical example. But who was typical? For the great characteristic of the movement was its vagueness. Ethicists were deliberately disunited, and the 46 (non affiliated) branches which the movement had acquired by 1906, mainly around London, varied hugely in their character. Ethicists in Bloomsbury were very English – intellectual; ethicists in Bayswater were more outgoing and more American. The ethical societies were heroically tolerant of all shades of opinion, so long as it was contrary.

The ethicists evolved a form of public meeting which was almost but not quite like a church service, conducted by someone whose general resemblance to a clergyman was tempered by the fact that his accent was less likely to gentlemanly-clerical than Scottish-regional or tinged with transatlantic. Being militantly anti-individualistic, some groups did away with leaders altogether, appointing panels as “lecturers” instead.

The most flamboyant figure in Dr MacKillop’s marvellous collection of men possessed by Not-Quite-The Holy-Spirit is Stanton Coit, the virtual father of the movement, a red-headed Emerson enthusiast from the Mid West, who having been dismissed by the South Place ethicists for overvehemence, founded his own Ethical Church in West London, a building resplendent with a large Walter Crane mural.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate