This article was first given as a paper at ‘Freethought in the Long Nineteenth Century’, a conference held at Queen Mary University of London on 9-10 September 2022.

The people and places really responsible for fundamental political and social change often go unrecognised, particularly when they are associated with unbelief. The case of 28 Stonecutter Street from 1877 to 1900 perfectly illustrates this phenomenon.

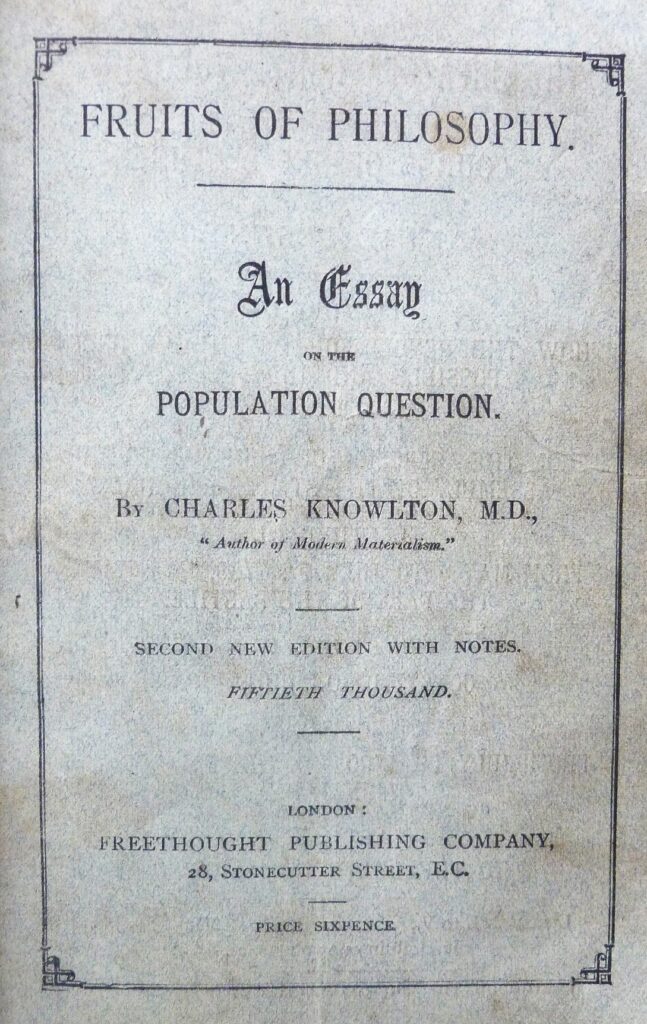

By the 1870s, the leading personality among militant British freethinkers was Charles Bradlaugh (1833-1891), who founded the National Secular Society (NSS) in 1866. Two of his closest associates were Annie Besant (1847-1933), an NSS vice-president, and Charles Watts (1836-1906), the first general secretary. They were Neo-Malthusians – in favour of birth control, or family planning, as we would call it today. In particular, they were advocates of a booklet entitled Fruits of Philosophy, which gave advice on contraceptive techniques. This was written by an American doctor, Charles Knowlton, and was first published in the US in 1832 and in England in 1834.

In 1876, a Bristol bookseller, Henry Cook, was sentenced to two years’ hard labour for selling the pamphlet, because it contained ‘obscene’ illustrations. How obscene we do not know, because no copies have survived, but it seems that the illustrations were Cook’s own and were inserted by him. Despite the fact that Knowlton’s pamphlet had been published for some 44 years, the authorities, their appetites whetted from their success in Bristol, decided to press on and prosecute Charles Watts, who had published it.

To the horror, disgust and fury of Bradlaugh and Besant, Watts pleaded guilty to publishing an obscene book, and thus escaped with a suspended sentence. Watts parted ways with his former colleagues amidst great acrimony. The rift was so great that Watts helped found a rival organisation to the NSS, the British Secular Union, before emigrating to Canada, where he lived until after Bradlaugh’s death. Watts had been a freethought publisher of significance; his departure left something of a void, which Bradlaugh and Besant were soon to fill.

Bradlaugh and Besant determined to test the law. They formed the Freethought Publishing Company and took out a lease on a property at 28 Stonecutter Street. In her biography of Annie Besant, Gertrude Williams describes it thus:

‘…a tumble-down building…a hundred yards up Shoe Lane from Fleet Street, past Wine Office Court and Gunpowder Alley. The narrow lanes hummed with the clank of presses and the air was heavy with the sweetish smell of paper and printer’s ink.’ [1]

It was from these premises that Fruits of Philosophy was republished in a new edition, with medical notes by Dr George Drysdale and a publisher’s preface by Bradlaugh and Besant. Bradlaugh delivered the first copy to the Chief Clerk at the Guildhall, and notified the police that at a specified time he and Annie would attend to sell the booklet in person. There were crowds in the street when the shop opened; the customers included some plain-clothes policemen, whom Bradlaugh identified from their boots.

For over 40 years, Fruits had been selling around 700 copies per year. In contrast, in its first three months on sale, the Stonecutter Street edition sold around 125,000 copies.

Bradlaugh and Besant had invited prosecution, and the authorities duly obliged. In June 1877, the trial began. The Solicitor General, Sir Hardinge Giffard, appeared for the prosecution – a clear sign of the importance attached to the case. Bradlaugh and Besant defended themselves. They used several arguments, ranging from freedom of the press to the value of contraception as an antidote to prostitution and infanticide, and as an essential way of relieving poverty and improving the lot of women.

The Solicitor General summed up as follows:

‘I say this is a dirty, filthy book, and the test of it is that …no decently educated English husband would allow even his wife to have it…The object of it is to enable persons to have sexual intercourse, and not to have that which in the order of Providence is the natural result.’ [2]

Despite a sympathetic summing-up by the Lord Chief Justice, presiding, the jury convicted. However, the decision was overturned on appeal on a technicality. Although this did not end prosecutions designed to prevent the dissemination of Neo-Malthusian literature, it did stem the tide as far as Fruits was concerned.

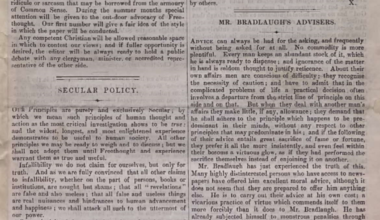

Bradlaugh and Besant had always had ambitions for their publishing venture that went well beyond the republication of Fruits. In Bradlaugh’s journal, The National Reformer, they announced their intention to make available ‘all works extant in the English language on the side of Freethought in Religion, Morals and Culture’. [3]

The business, initially managed by W.J. Ramsey, was a success and soon expanded beyond the capacity of No. 28. In 1882, Bradlaugh and Besant took out a further lease on premises at 63 Fleet Street, which, it is interesting to note, stood on the opposite corner of Bouverie Street to No. 62 Fleet Street. Half a century earlier, No. 62 had served as Richard Carlile’s ‘Temple of Reason’ and the shop from which he sold freethought works, including his Every Woman’s Book, the first book in English to advocate and explain contraceptive techniques.

Bradlaugh and Besant’s Company also published catalogues. The catalogue for December 1882 was divided into two parts, the first comprising exclusively Company publications, of which there were 45 books and 176 pamphlets, as well as, for the enthusiast, three different photographic portraits of Bradlaugh and Besant. The second part comprised some 200 remainders on the radical or freethought themes of the day, including political reform, the emancipation of women, Neo-Malthusianism, republicanism, biblical criticism and theology.

There were also reports of debates with clergy and other religious figures who were game and confident enough to take on the likes of Bradlaugh. These must have been great spectacles, as well as useful fundraisers: the debating halls were generally packed over several nights, and the audience paid for admission.

Stonecutter Street was also the British publisher of the writings of Robert Green Ingersoll (1833-1899). He was generally known as Colonel ‘Bob’ Ingersoll, having acquired his military title in the American Civil War. He was also Bradlaugh’s contemporary; some nicknamed him ‘America’s Bradlaugh’. He was certainly America’s leading infidel lecturer, and his writings sold in huge numbers. At the time he had a great influence on radicals on both sides of the Atlantic, including many involved in the foundation of the Labour Party; today he is almost entirely forgotten.

Finally, there were 26 publications associated with the scientific lecture courses held at Bradlaugh’s Hall of Science on Old Street. Books could be purchased at the shop or by post.

By the end of the 1880s, Bradlaugh was exhausted and ailing, and Besant’s interests had moved onto socialism and then, more strangely, theosophy. In 1890 they dissolved their partnership, the lease on 62 Fleet Street lapsed, and the publishing business and the lease on 28 Stonecutter Street transferred to my great-grandfather, another Robert Forder. Robert had replaced Charles Watts as NSS secretary in 1877 and first managed the publishing business in 1883, at a time when William Ramsey was imprisoned for blasphemy, along with G.W. Foote, for publishing the Freethinker.

28 Stonecutter Street is significant for other reasons. It was the birthplace of the Freethinker, founded by G.W. Foote, in 1881, and for a time it was the address of his ‘Progressive Publishing Company’. It was also the initial headquarters of the Malthusian League, whose first secretary was Annie Besant. The League was later to evolve into the Family Planning Association, which was founded in 1930 by Charles Vickery Drysdale.

However, most significantly, 28 Stonecutter Street was the place from which hundreds of thousands of birth control pamphlets were disseminated throughout the land during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Although it is not easy to calculate the numbers, some estimate is made possible by the publisher’s practice of including print numbers on individual pamphlets. Between 1887 and 1900, at least half a million 6d pamphlets were sold, and it may be closer to a million. Copies were also translated into several languages and widely sold in North America and Australasia.

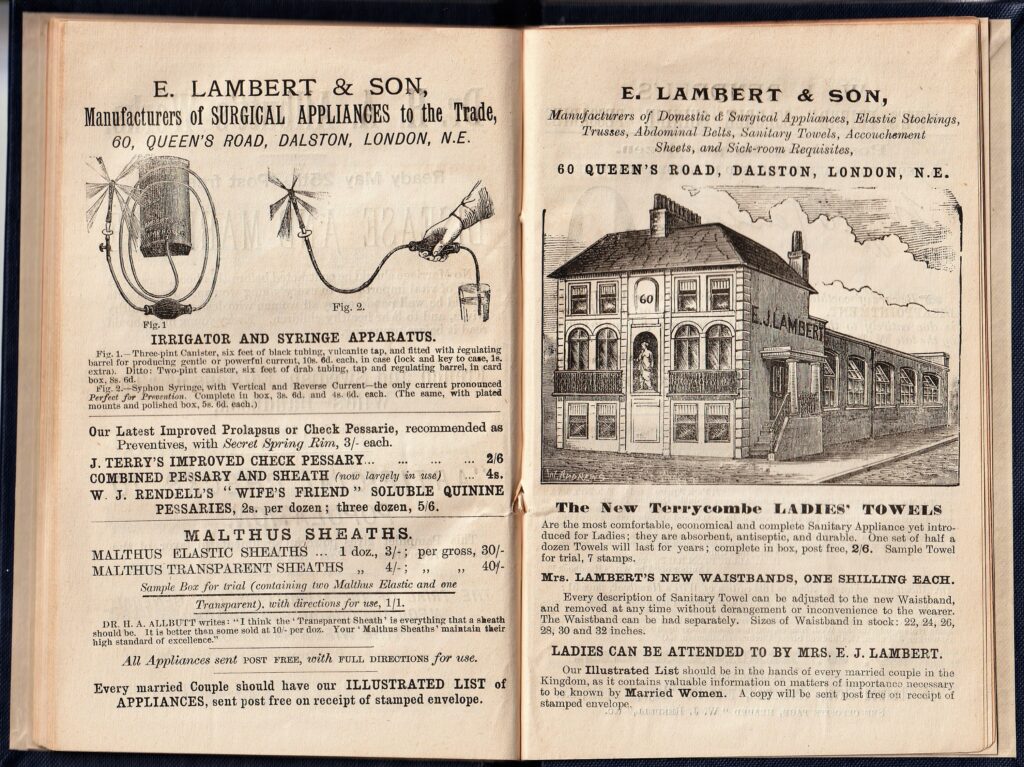

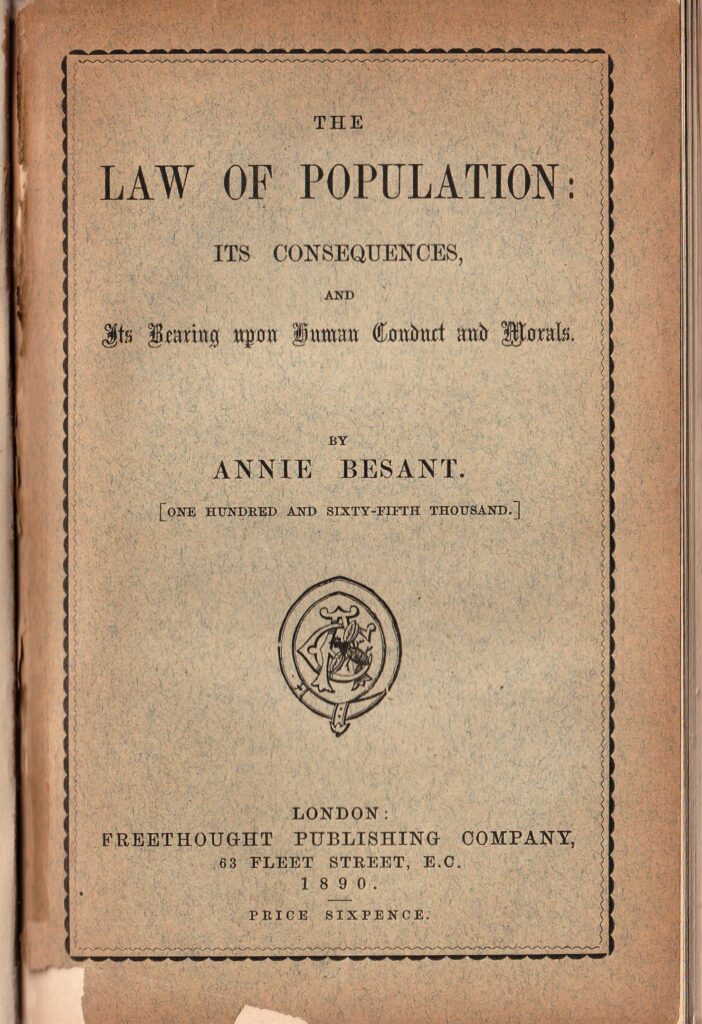

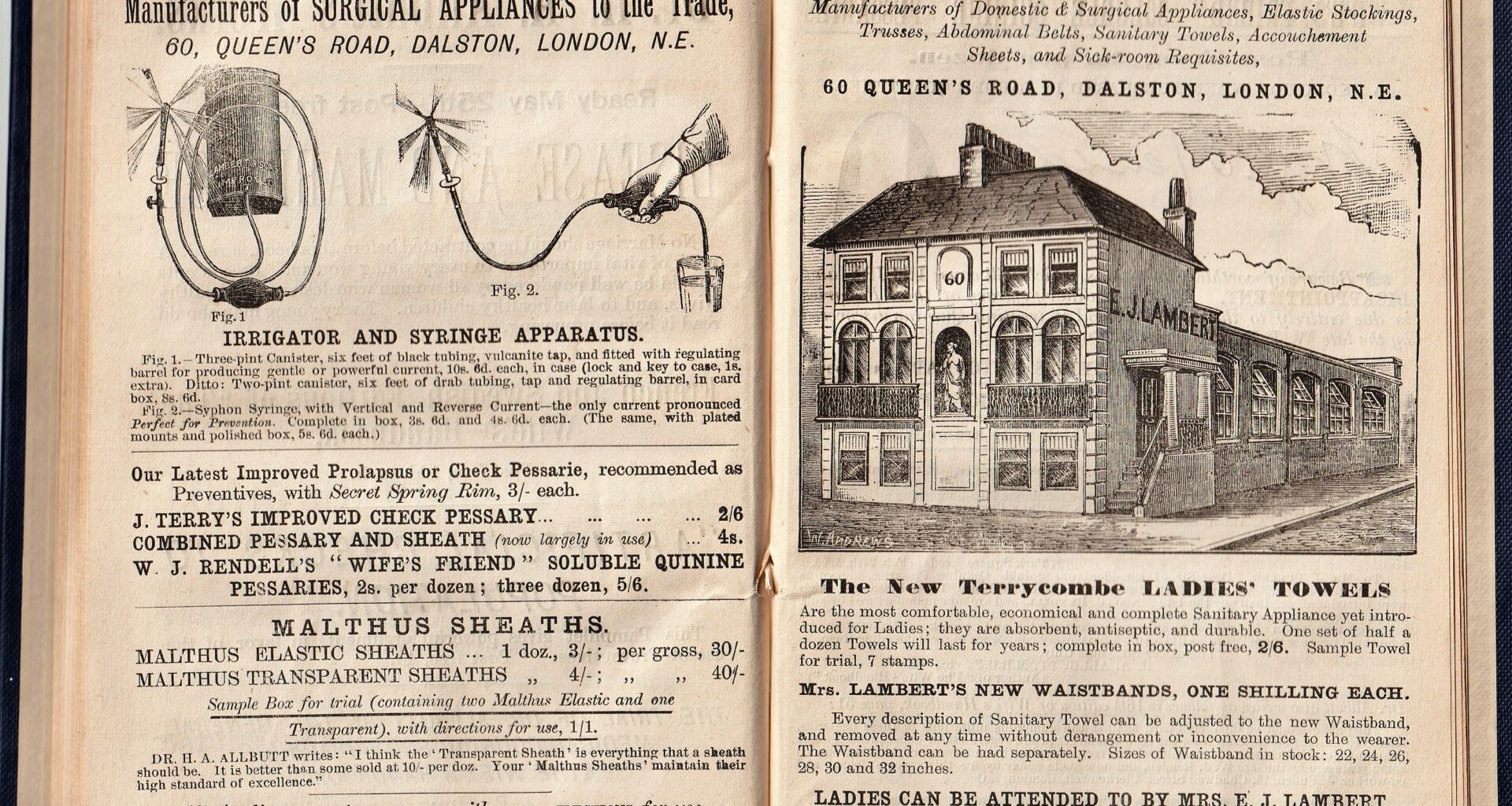

There were three main pamphlets. First there was Knowlton’s Fruits, of which around 125,000 copies were sold in the three months after republication in 1877, and more after that. Fruits was replaced by Annie Besant’s Law of Population, which she wrote to provide readers with updated advice; this was published in late 1877, first in the National Reformer and then, in an expanded form, as a pamphlet. Around 200,000 of the pamphlets were sold before Besant withdrew the title upon leaving the freethought movement. Her book was in turn superseded by Dr Henry Allbutt’s Wife’s Handbook, which remained in print from 1886 until the 1920s. The Wife’s Handbook was undoubtedly the best publication, featuring illustrated advertisements as informative as the text: around 500,000 copies were sold from Stonecutter Street. Unfortunately for Allbutt, it led to his being struck off the register. He remains an unsung hero of the family planning movement, of public health and women’s emancipation. Marie Stopes, a great self-publicist, eugenicist and Christian, receives far too much credit. The hard yards came before her.

The 28 Stonecutter Street story came to an end in 1900. Robert Forder’s wife died in 1898, and his health was failing. Foote, by then President of the NSS, endeavoured to resurrect things, first with a new Freethought Publishing Company Ltd, and then the Pioneer Press. Both were worthy, but never rivalled the range and quantity of publications of their predecessor. In the early twentieth century, the mass market came to be catered for by the Rationalist Press Association, with series such as its ‘Cheap Reprints’ and ‘Thinker’s Library’.

Today, the remains of 28 Stonecutter Street lie under the glitzy London headquarters of Goldman Sachs. Every couple of years I contact them, offering to write a few lines about 28 Stonecutter Street. I have in mind a plaque, booklet, or something like, that but I have never received a reply. I cannot help thinking this is something of a metaphor for what happens to the history of freethought in general. They bury us and ignore us. Or am I being unfair?

[1] Williams, G. (undated) The Passionate Pilgrim. A Life of Annie Besant, John Hamilton Ltd., pp. 84-85.

[2] (1877) In the High Court of Justice, Queen’s Bench Division, June 18, 1877. The Queen v. Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant, Freethought Publishing Company, p. 251.

[3] Besant, A. (1885) ‘Autobiographical Sketches’, Freethought Publishing Company, p. 119.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate