Religious dogma inevitably hinders progress. Theological codification, in turn, institutionalises societal decay. Today, nowhere is this more starkly visible than in Muslim communities.

Much of what ails the Muslim world today is rooted in Islamic text. From the subjugation of women to violence against freethought, many of the human rights abuses in Muslim-majority countries are justified via Islamic scripture and jurisprudence.

Democracy remains sidelined in these countries, with even aspiring secular states granting constitutional sovereignty to Islam. The glaring lack of modern Muslim contributions to science, technology and global development owes much to the Quranic undermining of the value of life in this world, in turn upholding a fixation with a collectively imagined ‘afterlife’.

Yet merely stating these obvious, not to mention ominous, realities can get critics accused of ‘Islamophobia’, even when the critics themselves come from within Muslim communities. This refusal by the community at large to acknowledge the symptoms naturally hinders any cure for the ailment: the imposition of Islam on Muslims.

Vedic faiths such as Hinduism allow for intrinsic dissenting space within the religious domain, while some Christian and Jewish traditions have been able to forge identities that are not bound by literal adherence to their scriptures. Muslims, meanwhile, are forced to accept absolute Islamic authority, even if they individually lack canonical devotion – leading lives in accordance with the scriptures – or ritual practice. This approach not only sustains Islamic inertia in Muslim communities, it intrinsically views any irreverence of Islam as something alien.

From Taslima Nasrin to Ayaan Hirsi Ali, many of the staunchest critics of Islam from within the tradition have not only had their books banned in Muslim countries, they have been discredited as outcasts. Their own critiques of Islam seem to reciprocate this rejection by betraying the parlance of an outsider, sometimes showing the same disdain for Muslims as they would for Islam. Salman Rushdie, the attack on whom in August was another grim reminder of the price of mocking Islam, has long been pigeonholed as a ‘blasphemer of Muhammad’, despite decades’worth of writings about the Indian subcontinent, including its multi-pronged identity crises.

The security threats facing Rushdie over four decades explain why those Muslim-heritage authors who have focused the entirety of their writings on the rejection of Islam, such as Ibn Warraq and other vocal ex-Muslims, have had to use pseudonyms to dodge Islamic blasphemy codes and the violence that inevitably follows. These authors too are dismissed as unrepresentative voices, even as anonymous atheism escalates across Muslim countries. This has meant that the overwhelming majority of the writing and scholarship on Islam that is produced worldwide, including in the West, continues to be done from within the confines of the religion.

A common theme among these contemporary thinkers arguing for Islamic modernity, including Reza Aslan, Khaled Abou El Fadl, Shahab Ahmed and Mustafa Akyol, is the endeavour to stretch the restrictive boundaries of Islam, but not to erase them. Even when thinkers such as Abdolkarim Soroush challenge scriptural authority, they do so from the perspective of human fallibility, not as a rejection of divinity: in other words, they justify contentious Islamic commandments in terms of the limitations of human comprehension and not in terms of the absence of a supernatural origin. Thus Muslim authors, from Islamists to modernists, continue to treat almost identically held Islamic doctrines as the starting point of their arguments. This is also why the ‘Medina state’, traditionally the first Islamic regime built by Muhammad, continues to be presented as a superlative embodiment of both an Islamic and a secular realm by the ideologically antipodal advocates of the same religion.

The treatment of the much touted ‘Golden Age of Islam’ is no different. There is no doubt of the significance of Arab and Muslim contributions towards science and philosophy between the 9th and 15th centuries AD, but that had little do with Islamic scriptures. All attributions of scientific advancement of that time to the Quran or Hadith (the sayings of Muhammad) depend on a kind of ‘Texas sharpshooter fallacy’, with the credit being claimed after the inventions and discoveries had been made.

Meanwhile, many of the practitioners of Islamic thought and jurisprudence, such as Abu Hanifa, Maalik Ibn Anas, Ibn Idrees Shafiee, Ahmad ibn Hambal, Ibn Abi Aqil, and Ibn al-Junayd, continue to be identically venerated as absolute authorities in Sunni and Shia Islam, and much of today’s Islamist hegemony is rooted in their writings and the schools of thought they founded. Yet it was the rationalist, not the religious, philosophy that was the most noteworthy contribution of the early Muslim authors to global thought. For which, many of the humanist Muslim philosophers were targeted as heretics.

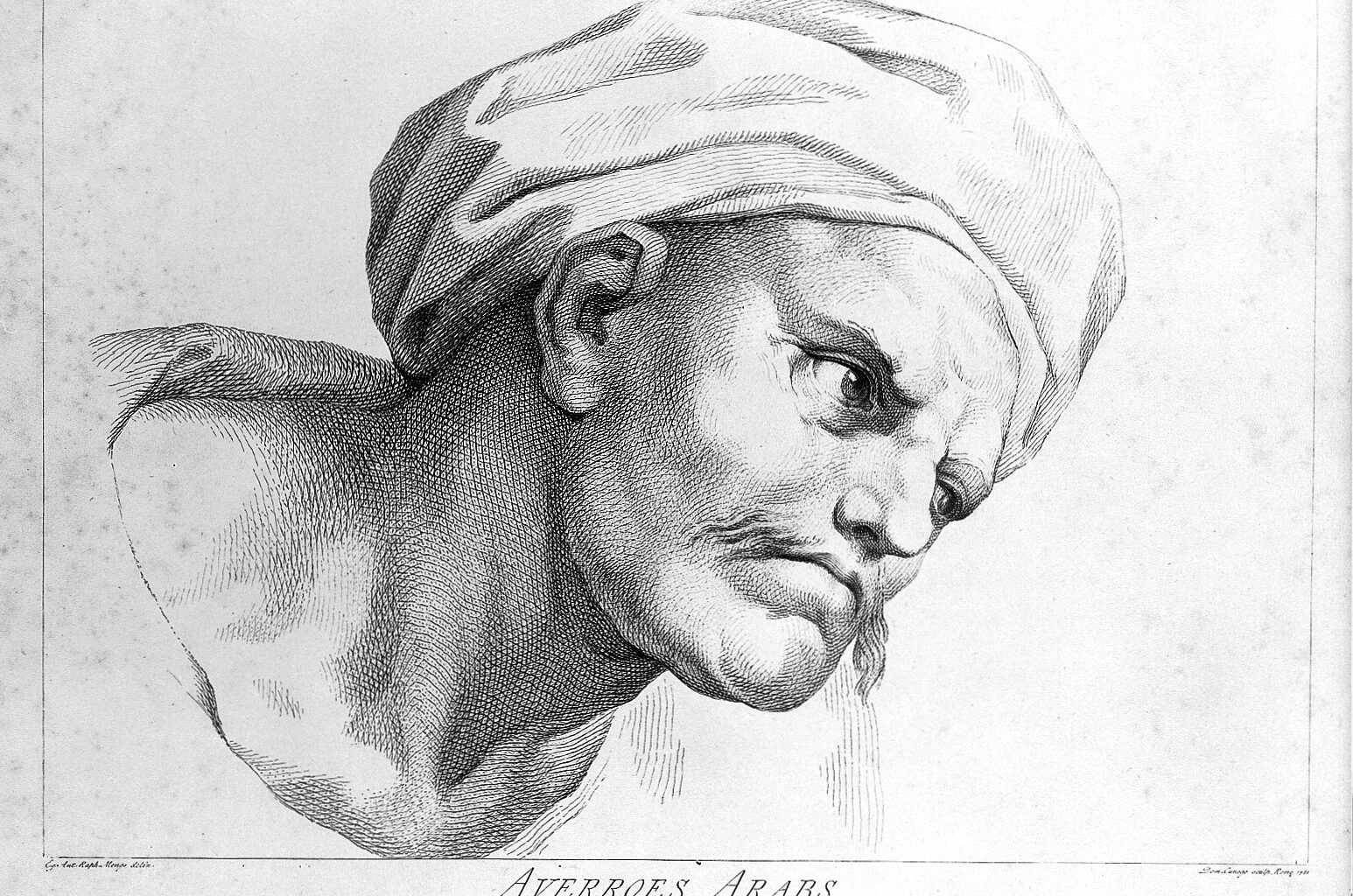

A paradigm case is the 12th century philosopher Ibn Rushd, Latinised as Averroes, who has been dubbed by many the father of Western secular thought. Rushd argued for pluralism in Islamic jurisprudence. His challenge to Islamic orthodoxy resulted in his being banished from Cordoba. Thus, while Ibn Rushd continued to inspire Western philosophy and political thought in the Middle Ages, his works remained largely sidelined in the Muslim world until the 19th century.

Like Ibn Rushd, many early Muslim rationalists, such as Ibn Sina and Al-Farabi, were deemed heretics. Most notable among their critics were Al-Ghazali and Ibn-e-Tamiyyah – two of the theologians that have had the longest-lasting impact on Muslim thought and continue to be cited to substantiate Islamist politics. Similarly shunned were the Muʿtazila, the rationalists that challenged Quranic literalism and sought to subordinate theology to reason between the 8th and 10th centuries in what today is Iraq, inspiring modern liberal theologians like Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd.

Looking at the fate of even those rational thinkers of the time who did not explicitly reject Islam or theism, and who were largely looking to reconcile science and reason, it is clear that irreverent scepticism and freethought were not exactly embraced even in the celebrated periods of Islamic rule.

Today, it is common in the Islamic world to eulogise past empires from the Ummayad to the Ottoman, as well as the ‘Golden Age of Islam’. But this narrative betrays an academic revisionism which enforces an Islamophilic understanding of the Muslim past and present. This reintepretation of history is taking place, while at the same time the cultural relativist narratives of Orientalism and ‘Islamophobia’ are used to silence criticism or enquiry into Islam for ideological reasons. Intellectual progress in the Muslim world is currently hindered by scholarly bias in favour of Islam and its history, where making the obvious link between jihadism and Islam, or probing the veracity of claims in Islamic tradition, is deemed to be targeting Muslims as a whole. To change this, Muslim heritage thinkers not only need to embrace rationalism, but also to rekindle irreverence for Islam. In fact, the long history of Muslim countries contains many examples of irreverence and the questioning of religion.

One notable example was the 9th-century philosopher, Abu Bakr al-Razi, a deist who criticised Islam and mocked the very idea of Quranic revelations. In Fi al-Nubuwwat (On Prophecies) he challenges the Quranic claim that a text like it cannot be produced:

‘Indeed, we shall produce a thousand similar, from the works of rhetoricians, eloquent speakers and valiant poets, which are more appropriately phrased and state the issues more succinctly… You are talking about a work [the Quran] which recounts ancient myths, and which at the same time is full of contradictions and does not contain any useful information or explanation.’

Al-Razi’s contemporary Ibn Al-Rawandi was an outspoken antitheist, described by historians as someone who upheld ‘atheistic ideas, the negation of Allah, the denial of Quranic prophecy, and the vilification of the prophets’. His Kitab al-Zumurrud (The Book of the Emerald) is presented as a theological dialogue in which he is a participant, called ‘the heretic’, arguing that ‘Muhammad’s own presuppositions and systems show that religious traditions are not trustworthy. The Jews and Christians say that Jesus really died, but the Quran contradicts them.’

Abu al-Alaa al-Maarri, a renowned 10th-century poet and anti-religion deist, used parody and sarcasm in his assault on Islam, even satirising the Quran in Al-Fuṣul wa al-Ghayat (‘Paragraphs and Periods’). A famous couplet of his in Arabic is translated as:

‘Muslims are stumbling, Christians all astray,

Jews wildered, Magians far on error’s way.

We mortals are composed of two great schools

Enlightened knaves or else religious fools.’

Abu Nuwas also used satire in his poetry in the 8th century, not just to target the Abbasid Caliphate, but even to express mockery for Islamic scriptures via homoeroticism. In one exchange he is reported to have used Quranic verses to woo a male lover.

As with much of early Islamic history, there is debate over the accuracy of the reported heresies that many of these dissidents, and others like them, were charged with. Their successors have often attributed their blasphemies to lies made up by rivals, or sectarian attacks, so as to sanitise those critiques that could be reconciled with Islam.

Conversely, there also are question marks over the sincerity – not to mention authenticity – of those rationalists who worked within boundaries of permitted Islam. Conflating deism or pantheism with Islamic characteristics could simply have been a means to avoid being censored and attacked, or even to make their ideas palatable for realms immersed in Islamic theology. The Egyptian philosopher Abdel Rahman Badawi argued in ‘From the History of Atheism in Islam’ that some sceptics steered clear of targeting belief in Allah as a whole, since it made their works likelier to be banished. This was the case with many anti-theistic ideas of the time that have only managed to survive till today via literature that counters those critiques.

Today, the ideological self-confinement of Muslim thought within Islamic boundaries is likewise an exercise in self-preservation and acceptability. Certainly, the attempt to reconcile religion with modernity can aid progress in Muslim countries. For example, it should not require complete rejection of Islam for aspiring Muslim scientists to deny the Quranic description of a flat earth, as long interpreted by Islamic scholars, even as recently as the 20th and 21st centuries. However, to seek to confine all intellectual enquiry within the bounds of Islam, however widely interpreted, is to prevent ideological pluralism. This in turn will keep Muslim freethought outside the realms of acceptability. In other words, as long as enquiry in Muslim countries is required to be sanctioned by religion, it will be limited in what it can achieve.

The authorities who hinder freethinking about Islam in this way, whether through sharia enforcement or via the ‘liberal’ denial of space for Islamic dissent, are actively suppressing the progress of Muslim thought. In doing so, they are hindering the intellectual growth of a quarter of the global population. It is only through unabashed irreverence and unapologetic rejection that Islam will find its due place in the modern world. That will finally allow Muslims to collectively embrace secular laws, to make intellectual progress on a par with other advanced countries, and to conduct their lives free from the hindrance of theological doctrine.

Today, however, whether in Islamist theocratic regimes like Iran, the now ostensibly liberalising Arab monarchies, or the heavily Islamised (though officially secular) democracies such as Indonesia, Islam remains a source of absolute power in the vast majority of Muslim states. The first step on the path to Muslim freethought needs to be a root-and-branch reform of the Islamic regimes themselves.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate