The death sentence of Salman Rushdie imposed by the late Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989 may have been, according to the analysis of the Iranian scholar Mehdi Mozaffari, technically not a ‘fatwa’ but a ‘hukm’: an order to kill the person stated. Unlike a fatwa, a hukm continues to be valid beyond the death of its author. Whatever the technicalities, Khomeini’s ‘fatwa’, as it is usually known, continues to be in force. This has been demonstrated less by the attempted assassination of Salman Rushdie on 12 August 2022 than by the reactions to it in the Islamic world. These indicate that the assassination attempt was rooted in religious ideology. This raises two questions:

1. How far are crimes like these directly related to religion? And to the extent that they are, why are these religions, their institutions and followers in open societies like those of western Europe, granted a privileged position in the state through exceptions from otherwise generally applicable laws?

2. Conversely, if there is no direct connection to Islam in such crimes, one difficulty for non-Muslims, and also for advocates of Islam themselves, is how to comprehensibly and precisely delineate which attitudes, statements and actions are ‘Islamic’ and which are not. Is it possible to draw a distinction that is sufficient to hold Islamic entities accountable for their pronouncements and to establish a duty to explain themselves?

The problem with cultural relativism

In the cultural relativism common among Western progressives, the connection between violence, murder and religion is often played down or even denied. The German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, for instance, commented on the events in Iran at the end of September in a speech in the German Bundestag:

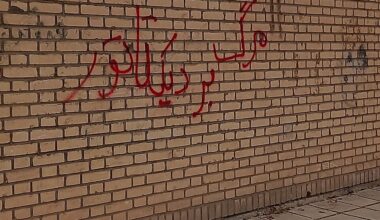

‘When the Iranian regime bludgeons women in the name of religion, it has nothing, absolutely nothing to do with religion! It is an expression of a power system based on humiliation & violence.’

She was referring to protesting women who removed their veils after the young Iranian woman Mahsa Amini was beaten to death by police a few days earlier for not wearing her headscarf ‘properly’. Meanwhile, the protests have resulted in over 600 deaths so far, according to a Wikipedia page which keeps track of them.

It can of course be argued that whether a headscarf is ‘correctly’ worn is not a simple matter of Islamic doctrine, but of interpretation and culture. However, that does not mean it has nothing to do with religion. Baerbock is right about one thing: the Iranian regime is indeed a system of power based on humiliation and violence. However, its laws and their execution are also based on religious ideology: Iran is a constitutional theocracy. Islam also forms the basis of a state religion in more than twenty other countries, leading to an ideological congruence of politics and religion.

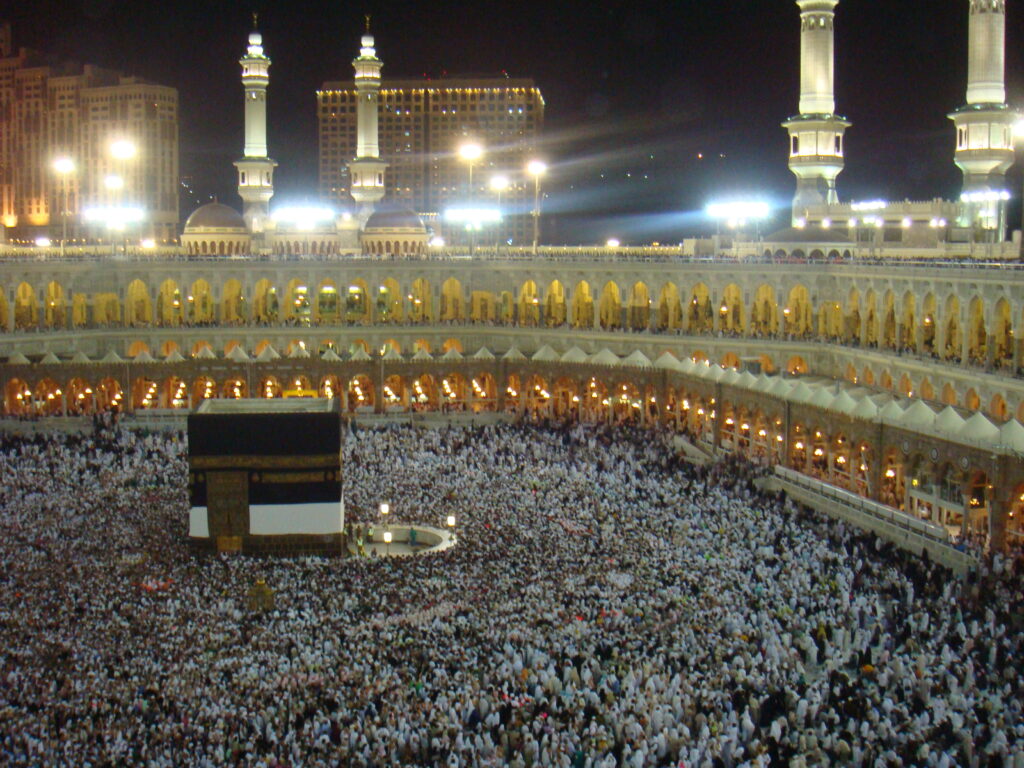

The fatwa in Europe

In Islamic states with their state religions, secular and religious laws may be interchangeable. But this does not mean that fatwas are a phenomenon limited to the Islamic world. Islam is also part of European societies, and, in its organised form, is interested in spreading its teachings, legal opinions and injunctions among its followers – just like any other religion. In some countries, attempts are being made to control Islam through theological faculties at state universities. Education, however, is not limited to state institutions.

Political scientists Nina Scholz and Heiko Heinisch, experts in the field of political Islam, explain in an article in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung how the Institut Européen des Sciences Humaines (IESH) is training Islamic teachers for several European countries. The IESH was founded by the FIOE (Federation of Islamic Organisations in Europe), and has close ties to the Muslim Brotherhood. Unsurprisingly, there are overlaps in personnel with other religious organisations. One of the IESH’s deans, for example, is also deputy secretary-general of the ECFR (European Council for Fatwa and Research). This council, based in Dublin and Leeds, has made it its task ‘to transfer the application of Islamic norms to European conditions, i.e. to give advice to Muslims living here and to draw up fatwas.’ As Scholz and Heinisch also observe, ‘In its expert opinion, the Fatwa Council explicitly defends the right of Islamic states to condemn and execute apostates according to the Sharia.’

‘Radical fringe phenomenon’?

It must be emphasised that many Islamic associations, institutions and Muslims living in enlightened democracies have condemned atrocities carried out in the name of Allah. What cannot succeed, however, is to pretend that the above cases of Mahsa Amini and Salman Rushdie have nothing to do with religion.

Nor are these cases isolated. Evidence for this comes from the Iranian protests, and has also been highlighted by the Councils of Ex-Muslims of Britain and Germany. These councils bear witness to the numerous apostates who have fled Islamic states because of their sexual orientation, their criticisms of religion, and other violations of religious laws. But the persecution does not end at the borders of the Islamic world. The fatwa against Salman Rushdie led to a decades-long, worldwide manhunt, backed by a bounty of several million US dollars, and to other attacks (some of which were fatal).

The way in which critics of Islam and Islamic regimes have been murdered is undoubtedly linked to the religion itself. Moreover, such murders have been supported, accepted or at least tacitly condoned by notable sections of the Islamic world. This statement can be made with some certainty, although no figures are available at this point as to what proportion of Muslims worldwide approve of the recent attempt against Rushdie and Khomeini’s fatwa. The latest polls from the UK are decades old. It would be interesting to see how far this has changed in recent years.

It may well be that the majority of Muslims worldwide do not endorse Khomeini’s order. However, this is not sufficient to prove that such an order is incompatible with Islam. To see events like the attempt against Rushdie, the waves of terrorist attacks perpetrated by Islamic extremists in the last two decades, and the bludgeoning of protesting women, as all the effect of ‘radical Islam’, ‘political Islam’ or ‘Islamism’ may be, when all is said and done, reasonably accurate. However, the choice of words does not say much about how widespread the support is for this kind of violence. The public reactions from people calling themselves Muslims around the world to the attack on Rushdie were sometimes joyful, and were too many to be dismissed as merely ‘fringe’.

The monolith

At this point in the debate, the argument is often raised that Islam should not be perceived a homogeneous block. But even someone who does not study Islam is aware that this religion is interpreted in different ways by different sects and individuals. All of us know Muslims who share the values of liberal societies – as well as, at least from media reports, those who prefer to fight for the Islamic State. Distinguishing between these attitudes to Islam is not rocket science. We may assume that the average attentive media consumer has already heard of at least some of the main groups – Sunnis, Shiites, Salafists, Wahhabis, Taliban, and so on – and does not assume that they all adopt exactly the same views and forms of behaviour.

It is precisely the matter-of-factness with which these distinctions are made that should give pause for thought to those Muslims who distance themselves from the substantive foundations of their own religion. For non-Muslims, despite all their ability to make distinctions, it is hardly possible to attribute crimes carried out on behalf of Allah to a non-religious Islam or to a variety that is not tolerated within Islam. Attempts like the German Foreign Minister’s to say that those who commit crimes in the name of Islam are not really following the religion, or have misinterpreted it, rely on a type of ‘no true Scotsman’ fallacy.

If, then, some conservative or fundamentalist interpretations of Islam lead to violence and are inimical to liberal democratic values, it is all the more urgent for public advocates for a liberal interpretation of Islam to draw a clear line between their understanding of their religion and that of the fundamentalists.

The case of Austria

Of course, no private citizen has to justify themselves for things they have not done, and no one is answerable for the crimes of other followers, or purported followers, of their religion. But such crimes are problematic for organised and official Islam, and Islam as it is presented in public debate, since it wants to be perceived as a unity and as finely differentiated at the same time. The political approach of many European states in trying to categorise Islam, somewhat as was done under Turkish secularism, makes these difficulties of perception even worse. Turkey is considered a secular state, but it maintains an authority, the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet), to control Islam. This is not a model for the separation of republic and religion, but a nationalisation of religion.

Among the response of European countries to the Islamic diaspora, the situation of Austria has its own particular characteristics and history. The country inherited an ‘Islam law’ (Islamgesetz) which was enacted in 1912 under the Habsburg Emperor Charles I. The annexation of the territories of Bosnia and Herzegovina required that an autochthonous Islamic population be legally recognised in the state. The law survived two world wars and was replaced in 2015 – at a time when I was a Member of Parliament – by a new Islam law, which structurally follows the so-called ‘Israelite law’ (Israelitengesetz).

In some respects, however, Muslims in Austria are clearly placed at a disadvantage. In contrast to other religious communities such as the Catholic Church, the Islamic Religious Community in Austria (IGGÖ) does not receive any subsidies. Islamic organisations are also subject to a ban on funding from abroad, and must explicitly profess the fundamental values of the Republic. It is remarkable in itself that one religion is treated worse than another – and the compatibility of this with the ECHR is questionable – but the government’s plan goes so far as to create, in the IGGÖ, a counterpart which can be controlled by the state and which serves as a rallying point for the most diverse Islamic currents.

In contrast to Christianity, for which Austrian law recognises different denominations separately, Islam is considered under the Islam Act of 2015 as a monolithic bloc. If individual Islamic sects or currents do not fit into this and do not want to join the IGGÖ, they cannot exist as legal entities. This unity has been supported by both sides.

This is first of all demonstrated by the fact that the IGGÖ had already formulated a claim to sole representation for Muslims in its 2009 constitution, which can no longer be found in later versions: ‘Article 1 (5) All Muslims (without distinction of gender, ethnic origin, school of law and nationality) who have their main place of residence in the Republic of Austria belong to the Islamic Religious Community in Austria.’ Second, under the 2015 Islam law, Islamic associations that do not want to submit to the regime of the IGGÖ must be officially dissolved. Several such associations have in fact been dissolved under this provision. But this is not compatible with religious freedom, and illustrates the opportunistic lack of principle of the law-makers in matters of religion.

The monolithic stance in the current Islam law is driven by the shared interest of the IGGÖ and the prevailing policy of Austria to integrate anything that is Islamic into one instrument, in order to facilitate collaboration and control between state and religion. But in fact, all major religions break down into many sects and many more currents, up to and including personal interpretations of faith and position to the community. A state like Austria, which operates a cooperative model of state and religion, imposes on itself, at least in theory, the duty not to undermine this distinctiveness.

In practice, the inclusion of everything Islamic in a single religious community means that the IGGÖ also represents and is responsible for the radical fringes of Islam. In other words, thanks to the uneasy alliance between Austrian law and the IGGÖ, this organisation now legally includes sub-groups that are hostile to an open society. The question follows of why such an organisation should enjoy a special status in that society. This situation is neither logically comprehensible nor ethically justifiable.

On the level of principle, it also seems bizarre and unjust that individual ideologies, world views or religions should be granted exceptions from universally applicable laws. In a secular democracy, the fairer and more just solution would be to strip all legally recognised religions, including Islam, of their privileged legal status and associated privileges of all kinds, including tax exemptions, religious education in kindergartens, schools and universities, protection under blasphemy laws, and so on.

Islam in the open society

This leaves the second question posed at the beginning of this article, concerning the obligation on public representatives of Islam to explain what counts as ‘Islamic’. Is the murky boundary between cultural, ‘religious’ Islam that is not responsible for crimes like the attack on Rushdie, and the allegedly non-religious Islam which is blamed for such crimes, sufficient to hold Islamic entities accountable for violence committed in the name of their religion?

A secular observer cannot easily become an expert in the various currents, schools of law and doctrinal principles that have evolved over time within a complex and ancient religion like Islam. Such an observer can but judge the outward manifestations and effects of religious belief upon its followers. If Muslim organisations with significant public influence claim that those who practise violence in the name of their religion are not its true followers, then it is up to them to demonstrate this by clearly demarcating the boundaries between ‘true’ and ‘false’ Islam – or, if this is not possible, then at least between acceptable and unacceptable versions of it. Many Protestants today do not consider that the Catholic Church’s positions on women and homosexuals are really ‘Christian’ – and yet they cannot deny that unfashionable and inhumane attitudes are rooted in the teachings of Christianity as a common heritage.

As with Christianity, there are many dark as well as bright moments in Islam’s intellectual and cultural past. As also with Christians, there are, it is to be hoped, many Muslims who would like to see the development of a modern version of their religion: one which irrevocably cuts all ties with the violence in its heritage and which can be integrated into a liberal democracy. The onus is on these religious progressives, if they wish to prove that their interpretation of their religion is compatible with liberal values, to clarify its differences from more fundamentalist strains.

Enjoy this article? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on freethought.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate