We live in an era of steadily proliferating and competing orthodoxies. News feeds are curated on the basis of what users have already liked and shared, niche political communities that could not have existed a couple of decades ago are able to flourish online, and commentators are under immense pressure to give their fans what they want. This phenomenon is known as ‘audience capture’, and it has ensnared plenty of prisoners: former liberals who first moved toward the centre and are now on the far right; left-wing identitarians who care more about skin colour, gender and sexuality than ideas or principles; politicians who have become servants of increasingly polarised constituencies.

Public intellectual life in the twenty-first century is often reduced to a series of increasingly strenuous ideological purity tests. This leads to warped incentives, intellectual rigidity, and extremism: Oh, you have your doubts about the efficacy of vaccines? Well, I have my doubts about the entire system that authorises and produces them. I even think Bill Gates might be putting microchips in our arms. In political communities built around conspiracism and dogmatism, radicalism is a way to gain prestige and trust. This is an inversion of the role which responsible public intellectuals could play: instead of challenging the orthodoxies and assumptions of their readers and listeners, they offer increasingly high-decibel assurances that those orthodoxies and assumptions were right all along.

We have never been in greater need of authors, academics, and journalists who think for themselves rather than mindlessly conforming to the demands of their tribes. This is one of many reasons the absence of the late Christopher Hitchens is felt so acutely by so many. In his 2001 book Letters to a Young Contrarian, Hitchens warns: ‘Don’t allow your thinking to be done for you by any party or faction, however high-minded.’ As a former socialist, Hitchens knew all about the pitfalls of party-mindedness and factionalism. The main story of his political life was his realisation that maintaining a consistent commitment to certain principles required him to abandon a political community he had embraced for decades.

In a 2002 interview, Hitchens said: ‘If you’ve concluded that there is no longer an international socialist movement, that it’s not going to revive, you’re really only being a poseur if you say that you’re a socialist nonetheless. And that’s the position I’m in now.’ Yet Hitchens resisted the standard ‘conversion’ narrative: while his politics undoubtedly shifted after the Cold War, his principles remained constant. He even still claimed to ‘think like a Marxist’.

Hitchens despised the word ‘contrarian’, but it is not difficult to see why his publisher thought it was applicable. Martin Amis once observed that Hitchens had ‘always taken up unpopular positions,’ and has claimed that his friend had a habit of ‘saying something that went against the grain and then having to justify it. So that the Hitch was really debating with Christopher half the time.’ The problem with this view is its implication that Hitchens was taking controversial positions for the sake of controversy. But even the positions that were most unintelligible and infuriating to his left-wing comrades and liberal fans were grounded in his firmest principles.

Take Hitchens’s support for the post-September 11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Though he often made indefensible arguments in favour of these wars (about nonexistent weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, for instance), his central argument was always his view that universal human rights should be upheld around the world. He made a similar argument about defending Bosnia when it was under siege by Slobodan Milošević’s forces in the mid-1990s. He did not just view this campaign of ethnic cleansing and conquest as a humanitarian catastrophe: he argued that Milošević’s victory would ‘negate the whole idea of Europe.’ He supported the defence of Bosnia because he believed that was what his commitment to liberal democracy and internationalism required.

‘It matters not what you think,’ Hitchens wrote, ‘but how you think.’ Many assume Hitchens was such a pugnacious debater and polemicist because he was temperamentally inclined toward rhetorical combat. As Amis put it: ‘He likes the battle, the argument, the smell of cordite.’ This is true, but another source of Hitchens’s ferocity in print and on the stage was the fact that his positions were natural extensions of his core principles. It is easier to hold and defend a controversial position when you have internally coherent reasons for doing so.

What you think – or at least what you purport to think – tends to matter more than how you think these days. The best path toward a lucrative career as a political or cultural commentator is the development of a brand that serves a particular set of information consumers. There are plenty of fiery pundits and Twitter warriors out there today, but how many reliably outrage and alienate their own ‘side’? How many are willing to publish an article or a podcast that will result in a loss of followers and prestige within the group?

Although platforms like Patreon and Substack have ‘democratised’ the media, they are also powerful engines of tribal consolidation. When writers and podcasters are beholden to paying customers rather than advertisers, they are swapping one form of coercion for another. Instead of staying away from potentially contentious issues that might frighten advertisers, they avoid issues or positions that will upset their patrons. Meanwhile, they adopt a tone and arguments that will appeal to those patrons.

There are many examples. When the American pundit and YouTube personality Dave Rubin started the Rubin Report in 2013, he presented himself as a disaffected liberal who was honestly questioning the dogmas of the left. Now he is a militant right-wing partisan who hosts interviews with conservative politicians about subjects like the ‘Plan to Destroy America from Within.’ The American evolutionary biologist and commentator Bret Weinstein was once just asking questions about COVID-19 policies and mRNA vaccines, but he is now convinced that there is a grand conspiracy – implicating the federal government, pharmaceutical companies, journalists, public health experts, and many others – to mislead the public about the safety and efficacy of vaccines. ‘All our institutions have failed us,’ he recently declared to his followers.

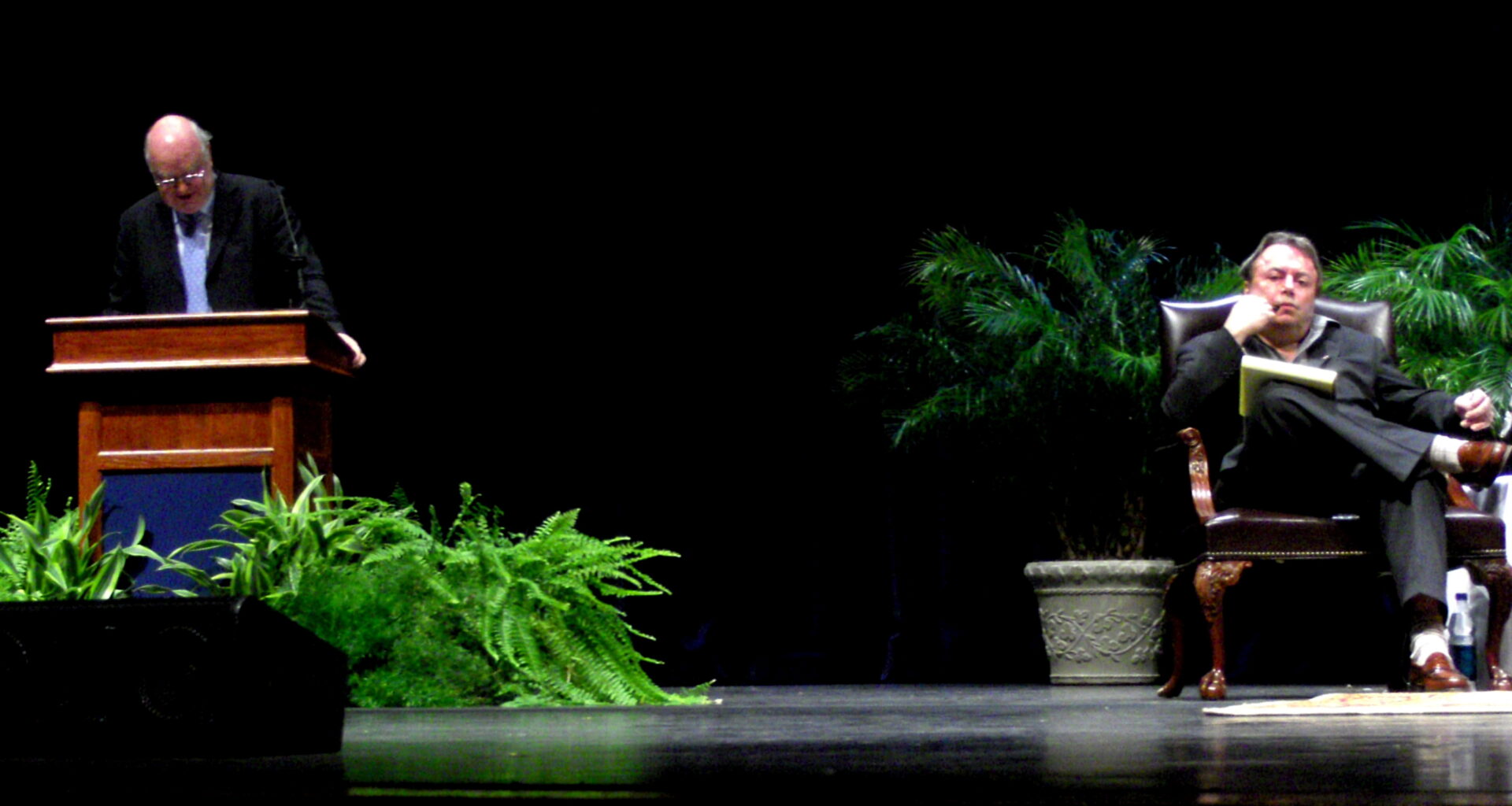

Hitchens never pandered to his audience. Many American liberals who embraced his criticisms of the Christian right despised his support for the Iraq War and decried his attacks on Islam. Conservative supporters of the war, on the other hand, were dismayed when he vehemently criticised Israel, declared that waterboarding is torture (after subjecting himself to the procedure), and signed up as a plaintiff in an American Civil Liberties Union lawsuit against the Bush administration for its warrantless surveillance operations. He had no problem sharing the stage with people who were natural allies on some issues and adversaries on others:

‘Any cause worth fighting for will attract a plethora of people: I have spoken on platforms with Communists about South Africa and with ‘Cold Warriors’ about Czechoslovakia; in the case of Bosnia I spoke with Muslims who disagreed with me about Salman Rushdie and Jews who suspected me because I have always supported statehood for the Palestinians.’

At a time when associating with or the ‘platforming’ of controversial figures often has serious reputational consequences, Hitchens’s ‘First Amendment absolutism’ is an anachronism. He once debated Tom Metzger, the former ‘Grand Dragon’ of the Klu Klux Klan, and his son on live television (see the YouTube clip above) and he argued that the work of Holocaust denier David Irving should not be suppressed. He believed that a genuine commitment to free expression could not be encumbered by concerns about guilt by association, and he thought the best way to expose bad ideas was to resist them publicly.

It is true that, these days, we are living in an era of algorithmically boosted speech, which is often weaponised to intimidate and harass people in the real world. It is unclear how Hitchens would have responded to the efforts of the sulphurous American conspiracist, Alex Jones, to pile further misery onto the lives of grieving parents who lost their children in the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting by sending an online mob after them (Jones told his audience that the massacre was staged as a ploy to steal Americans’ guns). What would Hitchens have said about the responsibilities of social media platforms in such a case? Even though he almost certainly would have despised President Donald Trump’s attacks on the press as the ‘enemy of the people’, it is difficult to imagine that he would have supported the decision to ban Trump from Twitter.

Would Hitchens have tempered his views on free expression in any way once it became clear how fundamentally the internet has altered the ways we share information and interact with one another? It seems unlikely, as he was so committed to the view that bad ideas should be openly and relentlessly challenged. But it is impossible to know.

There is one sense in which Hitchens’s position on free expression could not be clearer or more relevant: he believed writers should never censor themselves in order to remain in good standing with some party, faction, or political community. Nor should they allow the whims of public opinion to influence their work. ‘I don’t care about the crowd,’ Hitchens said in 2006. ‘I don’t care about public opinion.’ During the same discussion, Hitchens observed that the ‘main threat to free expression comes from public opinion’ and described this form of pressure as the ‘hardest to resist’.

The American essayist George Packer, a friend of Hitchens’s, echoed this observation when he observed that many writers today are hobbled by the ‘fear of moral judgment, public shaming, social ridicule, and ostracism.’ One of the reasons Packer believes a ‘career like that of Christopher Hitchens [is] not only unlikely, but almost unimaginable’ nowadays is the fact that writers ‘have every incentive to do their work as easily identifiable, fully paid-up members of a community.’ As this incentive becomes more powerful, our political culture will become more intolerant and censorious – and vice versa.

Hitchens understood how painful it can be to confront and ultimately part ways with your own side. He admitted that he sometimes missed his old political allegiances as if they were an ‘amputated limb’. But there were also times when the decision to abandon those allegiances felt to Hitchens like removing a ‘needlessly heavy overcoat’. Freethought is often thankless and difficult, but it can also be liberating – now more than ever.

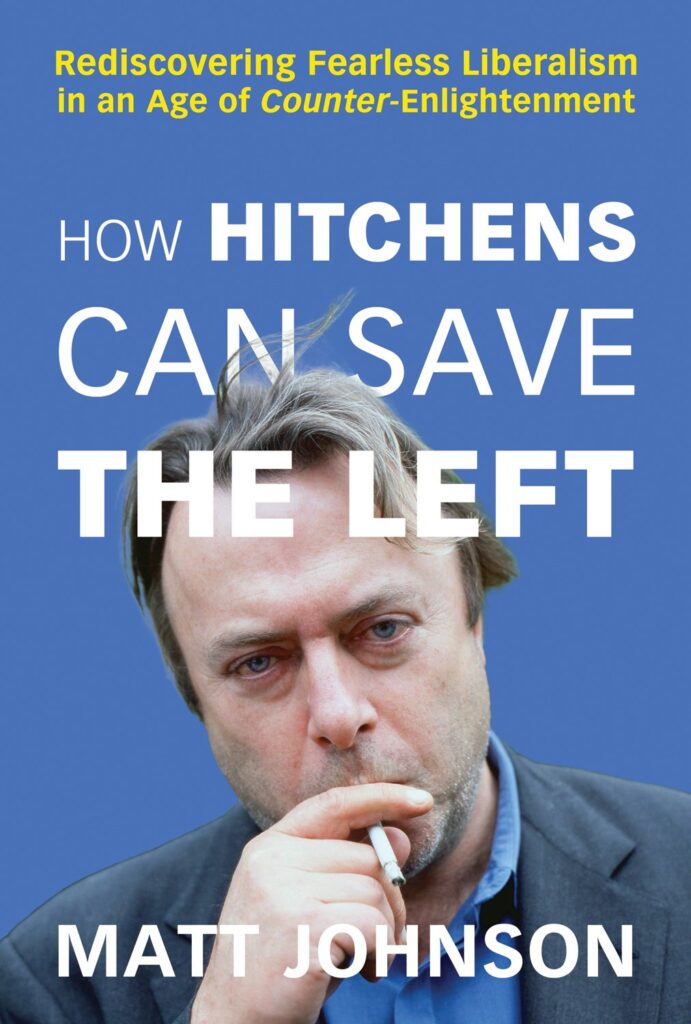

Matt Johnson’s book, How Hitchens Can Save the Left: Rediscovering Fearless Liberalism in an Age of Counter-Enlightenment (Pitchstone Publishing), is out on 28 February 2023.

Enjoy this article? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on freethought.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate