On April 26, I returned to my alma mater, the University of Edinburgh, to attend a film screening hosted by the Edinburgh chapter of Academics for Academic Freedom. The film, Adult Human Female, is a gender-critical documentary, which is all you need to know to understand why it has caused such a fracas.

The academics had tried to screen it last December but the event was disrupted and shut down by a gang of activists who took offence at the film’s content. I had not tried to attend that time, but thought I should go along to the rescheduled showing on 26th April. As it happens, I am not particularly interested in the gender wars. I have my criticisms of the radical feminists as well as the gender ideologues. But the gender debate is, among other things, a central free speech battle, and free speech is something I care about very much. I wanted to express solidarity with the organisers.

There was a loud protest outside the venue—a crowd of people behind a barrier, a loudspeaker blaring out cheesy music, and speeches about how evil the film was. Fine, I thought. They have every right to protest. But then I discovered that masked activists (apparently, or at least officially, unaffiliated with the protestors) had shut off all entries to the venue. University security could not remove them for fear of escalation, so the screening was cancelled.

You may say this is just another drama in the long, slow, agonising death of academic freedom and free speech at British universities. But familiarity should not breed complacency. Disruptions like the one I have just described should always inspire anger. They cannot be allowed to become normal, unremarkable events. Masked activists shut down, essentially by force, a screening of a film about an important and controversial matter of public concern – on a university campus, no less! If important and controversial issues cannot be debated at universities, then what exactly is the point of having them in the first place?

The details of the gender debate and of the disruption on 26th April are not the point here. The point is that the threat to academic freedom and free speech posed by ideological zealots – or self-righteous bores, as I prefer to call them – is real and dangerous. I bring up the Edinburgh example only as a recent illustration of this threat, and one which occurred shortly before I read Professor Steven Greer’s new book – and because it recurred to me often as I read it.

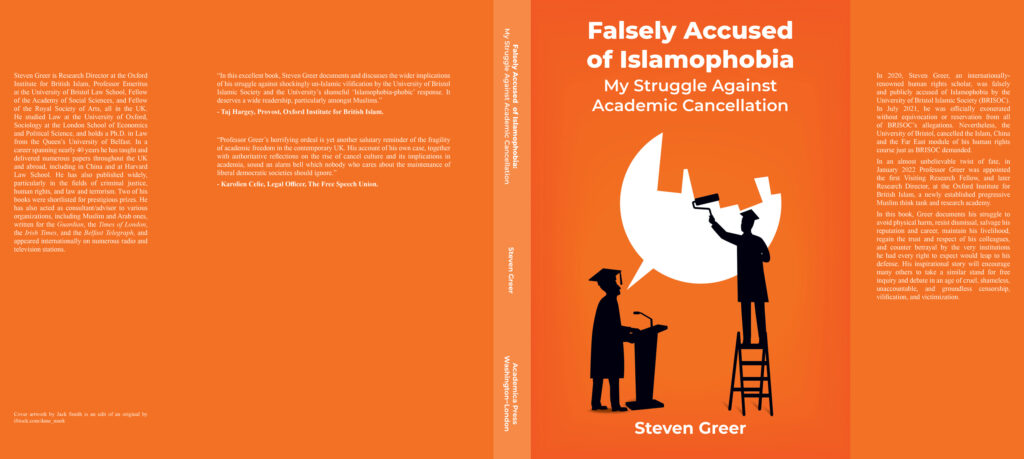

Falsely Accused of Islamophobia: My Struggle Against Academic Cancellation relates Greer’s experience of being silenced by people who did not like what he was saying. Greer’s story is in many ways different from the Edinburgh disruption, but at the same time shares some important features with it and with other recent attacks on free speech at universities. [See our interview with Greer – Ed.]

Greer, Professor Emeritus of Human Rights at the University of Bristol, was the target of a complaint by Bristol’s student Islamic Society (BRISOC) that he was an Islamophobic bigot who had, inter alia, mocked the Quran in a lecture and denied that Uighur Muslims were being persecuted in China.

The complaint was, as the merest glance at the evidence shows, full of lies and misrepresentations. In February 2021, BRISOC went public with their complaint and targeted Greer with a social media campaign designed to intimidate him into apologising or resigning. Later that year, Greer was completely cleared of all charges by the university. Throughout all this, the University of Bristol, and Greer’s own Law School in particular, were either useless in the face of, or actually compliant with, BRISOC’s harassment of Greer.

Greer has since retired from Bristol and has become the Research Director at the Oxford Institute for British Islam. He is currently pursuing litigation against his old university. In Falsely Accused of Islamophobia, he aims to put his story down comprehensively, rebut publicly all the allegations made against him, and persuade universities and academics to take the threat posed by what he calls ‘illiberal leftism’ more seriously.

In writing this book, Greer has provided a document that is very valuable to those of us who care about academic freedom and free speech. He forthrightly defends himself and expertly dismantles the pathetic case that was made against him. And, in a chapter reflecting on the broader trend of illiberal leftism on campuses, he shows that ‘cancel culture’ and the like are not right-wing myths but real – and dangerous – phenomena.

Perhaps even worse than the cases of campus authoritarianism that make the headlines are all the cases which are less dramatic in their cause, and which do not garner as much media interest, but are no less chilling in their effects. Indeed, although it is impossible to know how many students and academics have self-censored in fear of the consequences they could face for expressing an unfashionable opinion, it is almost certainly a large number. Greer cites the cases and the data to prove that cancel culture and campus illiberalism are, even if their extent is sometimes exaggerated, very much not merely products of right-wing fantasy.

There are, however, some stylistic problems with this book. In some ways, it is too academic. For instance, chapters are mapped out at the beginning and summarised at the end, textbook-style. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it does make for sometimes repetitive, bloated reading. It certainly makes it less engaging.

Greer also uses language—“snowflakery” or “wokeism”—that is likely to put off the very people he is trying to reach. To be clear, he defines these terms correctly and uses them in very precise ways. He is not frothing at the mouth and screaming ‘TRIGGERED SNOWFLAKES!!!’ Unfortunately, however, his use of this language will make it easier for his enemies to dismiss him as just such a frother.

Finally, the book could have done with a more thorough copy-edit. The overuse and occasional misuse of commas is distracting. For example: “What might be done to tackle these toxic trends and to cultivate a more tolerant and less censorious, hair-trigger, environment?” Or: “The Committee, thus not only presumed to know more about the scope and remit of my research than I do myself; it also ignored the fact that…” Perhaps I am being pedantic and allowing my inner English teacher to come out, but this sort of thing is grating and destabilises my reading experience.

I said that Greer’s story is different from the Edinburgh film disruption, but that many of the core issues at stake are the same. This is true, so far as it goes, but it is not the whole story. There is one aspect of Greer’s case that distinguishes it from other campus controversies: it is a controversy involving one very sensitive religion.

Greer is correct to point out the strange alliance between ‘woke’ authoritarians and often-conservative Muslim students. In short: the latter are ‘oppressed’, so the former must stand with them in all things. Illiberal leftism is indeed at the root of many of our contemporary campus woes. But Greer’s story is about how he was targeted by an Islamic group – and yet, for some reason, he spends very little time on this part of the problem.

There are a few mentions of Salman Rushdie and Charlie Hebdo; and Greer writes, shockingly, of feeling so threatened that he had to leave his home for a few days. But mostly he blames illiberal leftism and elucidates the ways in which the Bristol Islamic Society’s complaint fits into that ideology. Indeed it does, but is there not another interesting and important story to be discussed here?

They may use the language of ‘wokeism’, but cries of offence and calls for retribution have long been used by illiberal Muslims. In fact, such cries have been used by all powerful religions throughout history. The illiberal leftists are neophytes in comparison. Could it be that the causal relationship is the other way around? That is, have the ‘woke’ inherited their brittleness from the religious impulse, rather than conservative believers adopting ‘woke’ language for their own ends? No doubt the original, godly offence-takers will adopt whatever garb seems most alluring at any given moment, but still, they did it first. It would have been interesting to hear Greer’s views on this subject.

Another difference between typical illiberal campus culture and Islamic illiberalism is that the latter comes with very real threats of violence and even murder. Think of Samuel Paty and the Batley schoolteacher in hiding for displaying an image of Mohammed to his class. Religious fanatics are past masters of cancel culture, in a much more sinister sense of the term. Greer’s neglect of the Islam(ism) theme is a puzzling oversight. But perhaps this is slightly unfair—after the trauma of being targeted by an Islamic mob, and with the examples of Paty and countless others in mind, Greer might be forgiven for glossing over the topic in this way.

I was also disappointed that Greer takes the silly word ‘Islamophobia’ at face value. Such an imprecise word, and one which has so often been used to demonise all critics of Islam as bigots, is a word not worth having. In defending himself from what he once or twice more properly calls ‘anti-Muslim prejudice’, Greer arguably gives too much ground. Defining Islamophobia as ‘visceral prejudice against Muslims and Islam based on myth, caricature and misrepresentation’ shuts off quite a lot of what I am sure Greer would consider legitimate criticism of Islam. The Charlie Hebdo cartoons were, quite literally, caricatures. Why should hatred, even blind, stupid hatred, of a particular belief system be equated with prejudice against a group of people?

By lumping together ‘visceral prejudice against Muslims and Islam [my emphasis]’, Greer makes easier the job of the fanatics who wish to equate the criticism of ideas and beliefs with bigoted hatred of an entire, and very diverse, demographic. Perhaps this is simply an issue of tone: as an academic specialist who has spent many years comparing human rights in the West, in Islam, and in Asia, Greer may be inclined to be cautious and careful.

Still, the choice is surely not between vile bigotry and respectful disagreement. Ruthless satire and the mockery of sacred beliefs—even hatred of and disgust at certain ideas—do not a bigot make. That is why terms like ‘anti-Muslim prejudice’ or ‘anti-Muslim hatred’ are preferable. They are much more precise and do not conflate bigotry against people with criticism, however savage or merciless it may be, of ideas. I think Greer would agree with this, but sometimes he comes off as too defensive. Again, perhaps this is understandable, given everything he has been through. Indeed, his descriptions of the personal consequences of the campaign of vilification against him are the book’s most moving, and angering, parts.

All in all, Greer’s book is an essential addition to the literature on cancel culture and academic illiberalism. And it is heartening to see him still fighting the good fight despite everything he has been put through. Those who ought to be ashamed are the Bristol Islamic Society and Bristol University itself, along with all those colleagues and acquaintances who sided with Greer’s harassers or, perhaps even worse, maintained a cowardly silence in the face of all the lies and the intimidation.

It is to be hoped that more academic victims of cancel culture will write their own stories in future. If they do it half as comprehensively as Greer has, then they will have achieved something extremely important: they will have rebuked – and exposed – their persecutors.

Falsely Accused of Islamophobia: My Struggle Against Academic Cancellation, by Steven Greer, was published by Academica Press on 13 February 2023.

Enjoy this article? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on freethought.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate