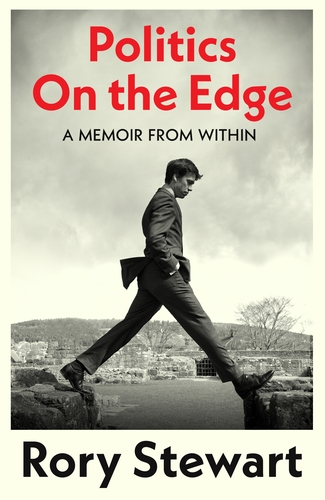

It is rare for a political memoir to be anything but a blandly written exercise in self-congratulation, and it is to Rory Stewart’s credit that his is lively, readable and self-conscious. His Politics On the Edge: A Memoir from Within is a valuable testament to the rot that has spread so far and so wide in British politics. He is also recognisably human in a way that slick careerists like David Cameron and Rishi Sunak are not. Stewart’s memoir reads like a memoir by an actual individual—another rarity of the genre.

Perhaps this is because Stewart came to politics late after a career in diplomacy and years of walking from Afghanistan to Nepal. Privileged his upbringing may have been, but he has had a full life outside of politics and evinces a genuine interest in people, places and principles—all things that are sadly lacking in much of our political class.

Stewart’s exposure of the farcical and ineffective inner workings of successive Tory governments since he was elected to Parliament in 2010 is damning. The scheming, dishonest, backstabbing, vulgar nature of politics is hardly news, but Stewart shows just how malignant the Tories have become ever since Brexit and the rise of Boris Johnson. His insights into the characters of figures like Johnson and Liz Truss, both of whom he worked directly under at different points of his political career, are as valuable as they are depressing, and expose them as the intellectual and moral pygmies that we already knew they were.

In the end, having failed in his bid for leadership of the party in 2019, Stewart resigned from the Cabinet and was purged by the victorious Johnson. This is another rarity in politics: Stewart had said he would not remain in the Cabinet if Johnson became prime minister, and, unlike so many who casually abandon their principles when they get in the way of ambition (Michael Gove springs to mind), he stuck by what he had said.

Would the Brexit debacle have gone ahead if Stewart had become prime minister? He states that he would have championed a version of Theresa May’s withdrawal agreement rather than the chaotic Brexit we actually got from Johnson or supporting a second referendum. Sensible as Stewart makes the May agreement sound, one wonders how he would have managed to get it through Parliament, given that May herself failed time and time again to do so. Appeals to sensible centrism had long since lost their persuasive powers in the Tory party.

One of Stewart’s less endearing characteristics is his somewhat self-important view of himself. In the book, he is a reluctant hero, come to save the Tories (and the rest of us) from a Johnsonian disaster. He is a defender of the centrist liberal consensus against right-wing radicals hell-bent on revolution. And he, the noble idealist, is slowly disillusioned by politics: ‘I felt myself becoming less intellectually inquisitive, coarser and less confident every single day.’ Elsewhere: ‘I began to feel that the longer I stayed in politics, the stupider and the less honourable I was becoming…’ In the end, Stewart seems to hate what he calls ‘this rebarbative profession’.

All this sometimes feels self-indulgent, albeit genuine. And, in fairness, Stewart does warn us from the outset:

‘I have tried to be honest about my own vanity, ambitions and failures, but I will have often failed to judge myself in the way that I judge others. I can see no way, however, of entirely avoiding the risks of personal memory in reconstructing a decade of life. The alternative would be blandness, evasion or silence.’

In avoiding those literary sins, Stewart is very successful. But one does sometimes tire of the ‘centrist saviour’ mode in which he writes: ‘[If Johnson’s] lies took him to victory, his mendacity and misdemeanours would rip the Conservative Party to pieces, unleash the most sinister instincts of the Tory Right, and pitch Britain into a virtual civil war.’ Stewart, of course, saw himself as the one to save us all from that outcome.

Lest I give a false impression, I did enjoy the book, and I admire Stewart. He is honest, decent and self-reflective, despite the odd lapse into the sanctimonious. And he is fundamentally right about the disaster that was Boris Johnson and Brexit. Though how Brexit could have been anything but a disaster, whatever form it took, is beyond me—Johnson’s deal was not, after all, radically different from May’s.

But he also misses something very important: the Tory Party was already rotten long before Johnson came to power. Stewart is initially sceptical about David Cameron, but comes to see him as the ‘last representative of the old Blairite liberal order’. And he positively swoons over Theresa May—in a recent interview with her on the podcast he co-hosts with Alastair Campbell, he called May ‘one of my genuine political heroes’.

Yet it was Cameron who promised a Brexit referendum to appease ‘the most sinister instincts of the Tory Right’, and May who, as Home Secretary, presided over the ‘hostile environment policy’ that led to the wrongful deportation of scores of non-white British citizens. A study commissioned by the Home Office itself found that the Windrush scandal was a result of decades of racist policymaking.

In other words, the worst instincts of the Tory party were nurtured, if not completely welcomed, from at least 2010, not 2016, and Stewart’s failure to see that, not to mention his failure to do anything about it while in Parliament, was his most serious flaw. The journalist Nick Cohen, in his review of Stewart’s memoir, puts it more bluntly:

‘Stewart cannot tell the whole story because he does not understand the failings of moderate conservatism. The most glaring is its self-delusion. There was no way the party would accept him or any other liberal conservative as its leader. The Tories are a hard right-wing party now and becoming more right wing with every passing year.’

Cohen is slightly too harsh on Stewart, but he is essentially correct. Would we have been better off if Rory Stewart had become prime minister? Probably. But how likely was that in the first place with a Tory party like the one we have had for quite some time? Not very. Stuck in a bubble of centrist conservatism, Stewart cannot help but miss this essential point. He is a principled, decent man who has lived a very interesting life. He is also very enjoyable to read. But the ‘good chap’ theory of politics has always been a flawed and foolish one, and Stewart’s blind impotence in the face of his party’s embrace of catastrophic populism is not charming in the slightest.

Enjoy this article? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on free thought. Or make a donation to support our work into the future.

2 comments

I admire many of Rory Stewart’s qualities too and look forward to his insightful contributions to his podcast. His evisceration of recent governments is total, troubling and humorous. But he is no secularist and is an enthusiastic monarchist.

Agreed! One interesting aspect of his book that might deserve greater attention is its almost complete lack of discussion of religion. He does mention being a monarchist, but religion is curiously absent.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate