A 16 year old girl, Armita Geravand, is one of the latest victims of the Iranian regime’s oppressive hijab laws. She was assaulted by the so-called morality police for not wearing a hijab. After going into a coma, she died in custody on 28 October.

The images of Armita Geravand in a coma are terrifying and disturbingly similar to those of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old woman who was killed by Iran’s ‘morality police’ for donning an ‘improper’ hijab.

According to reports, Mahsa Amini was tortured in the back of a police van. She died after suffering significant head injuries during this abuse. She became a global symbol of resistance to religious orthodoxy, and many people are determined to say her name in protest against the sexism and misogyny that is condoned by religious doctrine.

Tragically, the first anniversary of Mahsa Amini’s death has been marked by the death of another young woman in similar circumstances. This shows that there is still a long way to go in the struggle against the imposition of the hijab on women regardless of their views – both in Iran and elsewhere.

Some people, however, have chosen to actually ‘celebrate’ the hijab, rather than the brave women who have refused to wear it and in some cases died for their refusal.

In Smethwick, Birmingham, a 16-foot-tall steel statue depicting a woman wearing a hijab has been constructed and was due to be installed last month. The title, The Strength of the Hijab, which is written on a tablet at the statue’s base, is a betrayal of the brave women who refused to wear this restrictive clothing and were destroyed by their own resoluteness and dignity. Ironically, the statue that arguably celebrates a symbol of women’s submission to men was designed by a man, the sculptor Luke Perry. Perry said that he had drawn inspiration from ‘speaking to Muslim women’; according to his Instagram page, his ‘work is often about under-represented people’.

Underneath the title of the piece is the platitudinous statement, ‘It is a woman’s right to be loved and respected whatever she chooses to wear. Her true strength is in her heart and mind.’ This statement, superficially appealing but fundamentally vacuous, fails to acknowledge the utter lack of ‘love and respect’ shown towards so many Muslim women around the world, whether in forcing them to cover their hair or in persecuting them when they say ‘no’.

Regardless of the intentions of Perry and Legacy West Midlands, the charity that commissioned the statue, this ‘celebration’ of the hijab unfortunately cannot help but remind viewers of the utter indifference and lack of humanity that is prevalent in the authoritarian, brutal Islamic regimes where millions of women are forced to wear it.

Of course, in Britain, some Muslim women wear the hijab as a matter of personal choice and freedom of conscience. As long as this does not impinge on the rights of others, they should be free to do so, their choice should be respected, and they should not be discriminated against.

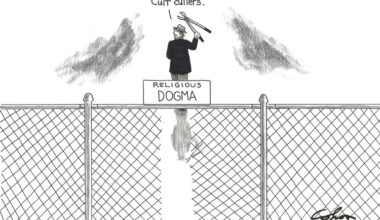

This does not mean, however, that the hijab as a symbol should not be open to criticism. Moreover, it is important to bear in mind that in countries like Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Afghanistan, Islamic governments routinely violate the rights of women who break ‘modesty’ regulations, subjecting them to imprisonment and harsh penalties.

Altogether, given the connotations of theocracy and violence against women which the hijab has in contexts around the world where it is not freely chosen, you might have thought that its presence was hardly something to be celebrated.

Moreover, the mere assumption that the hijab represents all Muslim women lends credence to the orthodox assertion that women who refuse to wear it are violating divine morality laws. This may embolden religious zealots who are already hell-bent on subjugating women in the name of religious modesty. Even in Western countries, women are regularly shamed, ostracised, tortured and in some cases even killed for not complying with this restrictive clothing regime.

Not long ago, a 17 year old Muslim girl was caught on camera twerking while wearing the hijab in a busy city centre in Birmingham. The video went viral on social media, drawing harsh reactions from certain members of the Muslim community. As reported by the Mail, she was called a ‘f****** s***.’ ‘Stupid b**** needs to be killed,’ another wrote. She received death threats. Apparently, it was not her dancing that landed her in this situation. Rather, she was abused and humiliated for dancing while wearing the hijab. She was forced to apologise publicly for ‘disrespecting’ it.

The brutal killing of Banaz Mahmod still evokes horrifying images in the mind. Born and raised in a highly conservative Muslim family, she was strangled to death by her father and uncle because she disobeyed the traditional teachings of Islam and tried to escape from an arranged marriage. Liberation from what are arguably cultish ideas was viewed by her relatives as a shameful deed that would bring disgrace on the family. She was strangled and her body was buried in a suitcase in Handsworth, Birmingham.

The problem is that these women who suffer in silence are often ignored in conversations about hijab culture. The dominant narrative on social and political issues has been dominated by religious fanatics. These fanatics self-identify as the guardians of religion, and somehow they have gained recognition as the representatives of their communities.

It is a dismal reality that religious zealots enjoy a privileged status in the UK. They exploit this position to bully individuals into compliance without facing any opposition from both inside and outside the community. They shield themselves from criticism by claiming the right to freedom of religion.

A new report by the conservative think tank Policy Exchange, The Symbolic Power of the Veil, has revealed how Islamists have been permitted to dominate the debate about the religious dress code in the United Kingdom and abroad.

The report makes five policy recommendations. Most significantly, it advises that ‘the government should resist any definition of Islamophobia that inhibits the public criticism of religious practices and traditions, including dress codes.’ It also recommends that ‘the government should refrain from publicly endorsing or promoting any specific religious attire, including events such as World Hijab Day.’

As reported in the Independent, the Labour MP Khalid Mahmood supported the key findings and recommendations in the Policy Exchange report. He pointed out that ‘the wearing of the hijab clearly does not represent all Muslim women. And it is grossly insensitive to those Muslim women in Iran, Afghanistan, Yemen and elsewhere who are compelled against their wishes to wear the hijab to declare that it does.’

The introduction to the report highlights ‘the importance of resisting factitious accusations of “Islamophobia” too often made by Islamists against those who campaign for the human rights and freedoms of people living under oppressive regimes.’ As it rightly observes, ‘in too many societies, the control of women’s bodies through religiously-sanctioned restrictions, including those relating to clothing, [is] a key tool of oppression.’

The findings of the report, in particular the way that accusations of ‘Islamophobia’ are being weaponised to suppress debate about women’s dress codes, should be a wake-up call for legislators and administrators. Sadly, for far too long, Islamist organisations that support restricting women’s freedoms in the guise of religious modesty have dominated the conversation on their religious attire. It is a sad fact that the authorities have long been ignorant of these issues, which remain some of the most pressing in British society today.

The authorities often seem oblivious to the fact that the normalisation of religious fanaticism further marginalises already marginalised groups in society – such as women in minority communities. Such fanaticism, and its tolerance, cannot but erode the liberal, secular and democratic principles on which British laws and customs are to a large extent predicated.

It is time to talk about truly ‘inclusive’ human rights which protect everyone, instead of pandering to divisive religious preaching. The misogyny of religious fundamentalists who overtly or covertly impose dress codes on the women and girls in their sphere of influence must be resisted, not appeased.

The presumption that all religious and cultural beliefs, no matter what their content, are entirely beneficial forces that should be accommodated at all costs, and celebrated rather than criticised, needs to be debunked.

It would be wise for Legacy West Midlands to reconsider the decision that led to the commissioning of this statue. Women should be honoured for who they are, not for what they wear. They should not be forced to carry the symbolic burden of any faith or culture. Reverence for a culture should not be used as a justification for ‘celebrating’ religious and cultural ideas that conflict with human rights.

2 comments

Really well put Khadija! This is exactly how I feel about the statue. I was shocked at the poor timing of it right around the anniversary of Mahsa Amini’s death. There are so many better ways to celebrate the diversity of the UK, than a symbol of opression.

There’s a saying: “What is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander”.

Put another way: should not the same dress codes apply to all?

If men insist on women dressing in a particular way, why do men not dress themselves identically?

If men insist upon women dressing in burkas why do men not do so too?

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate