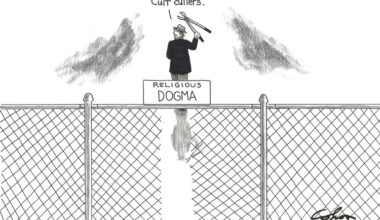

Advancements in scientific research have been overturning clerical hegemony in organised religions for the past two millennia. Religion has dominated the affairs of Muslim communities more than those of other religious groups; thus, in recent times, the challenge of science to religious authority has been a particular problem for the Islamic clergy. However, by limiting the spread of reason, and selectively adopting some but not all of the latest inventions, Muslim clerics have managed to forge a love-hate relationship with science and technology.

As a result, imagery and loudspeakers that were once declared haraam (forbidden) by the Islamic clergy are now at the forefront of daawah (Islamic evangelism). More recently, chatting, social media, Netflix, and the internet in general have faced fatwas (edicts declaring them haraam), while Islamic preaching has exponentially multiplied on the web. The latest frontier to have opened up is artificial intelligence (AI).

Much like the technologies mentioned above, the features of AI that enable Islamic preaching will doubtless be embraced.

In many instances, AI has already been adopted to facilitate Islamic practices: scores of apps have been designed to support Quranic learning, to streamline the timings and direction of prayers, and to browse Islamic TV shows. AI offers automated updates based on location, allowing users to locate their nearest mosque or halaal eatery. A particularly useful app, especially for non-Arabic speakers, is Quran Hero, which not only helps the user learn Arabic, but optimises time management; this is helpful for practising Muslims, who consume a significant chunk of their time in the five-times daily Salah.

In fact, evangelical AI practices are being embraced across religions: compare the rise of robot priests and mechanical sermons. Even though the dominance of clerics in Islam means that mechanised preaching is unlikely to be allowed, the religion too could theoretically incorporate AI in rituals such as Salah, where the imam is designated to perform certain steps and recite surah (chapters) – some of which are randomly chosen from the Quran. These steps could easily be outsourced to machines. The job of the muezzin (who proclaims the call to prayer) has already been co-opted by various apps: with the advent of such technology, the loudspeaker azaan ought to become redundant.

Once those supervising Islamic applications embrace the reality that not all Muslims have exactly the same beliefs and practices, AI can be more pluralistically incorporated. For instance, the vast majority of Muslims do not pray five times a day, because they have other (secular) commitments. Formally accepting this could help programme applications to merge work schedules with only those rituals that the individual believer wanted to pursue, and accordingly set reminders and alarms; in contrast, the loudspeaker azaan is for entire communities, at all times, regardless of the diversity of beliefs and practices. Embracing pluralism could also usher in new apps for progressive Muslims, such as those developed for Christians, which would incorporate beliefs and identities deemed sacrilegious or deviant in mainstream Islam, such as those concerning LGBT people.

Even so, formalising the Muslim rejection of Islamic tenets, and developing technology catering to diverse beliefs, is currently a distant prospect within the mainstream Muslim community, in which celebrated tech practitioners argue that Artificial Intelligence should be regulated according to Islam. Others condemn technological efforts to prolong life, and even the use of ventilators, on the grounds that ‘there’s a certain time for death, and you cannot delay it.’

Where fear of defying Allah even hinders attempts to save lives, the prospect that Islamic injunctions will be capable of being rejected via an app which is sanctioned within the Muslim community remains distant. This situation in turn maintains the Islamic clergy’s stranglehold over mainstream technology.

But has the internet not resulted in a wave of apostasies by Muslims? And if there are perfectly rational fears that an AI takeover might be inevitable, and more menacingly difficult to regulate, shouldn’t Islamic orthodoxy eventually have to make way as well? The problem is that the progress of Islam towards greater liberalism is being hindered both by the duplicity of mullahs and the complicity of Western ideologues. A glimpse of this can be seen through an examination of an AI tool that has made the headlines recently.

A casual conversation with ChatGPT on Islam reveals an artificially programmed reverence for the religion such as is expressed by devout Muslims or those demanding special privileges for Islam. The OpenAI chatbot, the GPT-4 model of which was released on 14th March, is not only well-versed in Islam, but can generate flawless commentary on the religion. There is just one caveat: the Generative Pre-trained Transformer’s knowledge of Islam is derived entirely from Islamic tradition and scriptures.

As a result, if one asks the chatbot about the origins of Islam, it will effortlessly narrate the history according to Islamic scriptures without offering any insights from those who have questioned the authenticity of these claims. Ask ChatGPT about the positive aspects of Islam and a long list is produced with the disclaimer that ‘these aren’t exhaustive’. If you ask it about the negatives, however, the result is disclaimer that ‘as an AI language model, I do not hold personal beliefs or opinions, and I do not intend to promote any religion over another’, followed by some common criticisms that the bot clarifies are ‘not universally accepted’, noting that interpretations vary.

It is true that ChatGPT offers similar disclaimers for other religions. However, further investigation reveals that it does not treat different religions alike. For instance, queries over errors in Bible generate responses highlighting those discrepancies, while the same question over the Quran produce a multitude of disclaimers, most commonly couched in terms of ‘differing opinions’, which the bot also employs in contrasting interpretations of the violent commandments. Similarly, while ChatGPT has no qualms in saying that ‘yes, there is a system of casteism in Hinduism’, it maintains that the question of whether Islam is sexist, or allows child marriage, is ‘a complex one’. ChatGPT can ape Shakespeare or Ghalib, but ask it to take up the Quran’s challenge to imitate its verses, and it refuses.

In short, most questions addressing the problematic aspects of Islam produce a general apologia, which often conveniently includes verse 2:256 of the Quran: ‘There is no compulsion in religion’. If the much-touted ambition of OpenAI was to create a chatbot that generates ‘human-like’ responses, it has been resoundingly successful in creating a machine that churns out only those views on Islam that are acceptable to Muslim orthodoxy.

While ChatGPT has undergone supervised pre-training to generate ‘appropriate’ responses on contentious subjects, including religion, its evident bias when it comes to Islam is also an offshoot of its transformer architecture. This architecture limits the bot’s generative ability to the available dataset, which it is then programmed to use in accordance with the pre-trained language guidelines. Even in the unlikely event that contrasting views were included in the dataset fed to ChatGPT on controversial issues, the algorithmic bias in favour of Islam was always going to be inevitable.

This is because, where texts lambasting casteism in Hinduism, or fallacies of the Bible, are widely available on the internet – often written by members of the communities whose beliefs are being targeted – the unhinged criticism of Islam is predominantly limited to anti-Muslim fora likely to have been flagged in the pre-training phase of ChatGPT. The prevalence of barbaric blasphemy laws in the Muslim world and the skewed ‘Islamophobia’ narrative in the West means there just are no sufficient digitally accessible data for even a theoretically ‘neutral’ generative AI. As a result, ChatGPT sometimes even refers to Muhammad using the reverential phrase ‘peace be upon him’, because of its repeated occurrence in the predominantly Muslim sources stored in the bot’s database.

This has resulted in an algorithmic bias not merely in favour Islam, but in particular in favour of the majority Sunni sect within Islam. For instance, if you ask ChatGPT about Abu Bakr, the first caliph according to Islamic tradition, the results which it provides are couched in terms of acceptance or eulogy, even though Shia Muslims do not accept his rule as legitimate. Asking the bot a question about whether Ali Ibn Talib is the First Imam of Islam – a reflection of Shia beliefs – results in a response that says it is a ‘matter of controversy’. Any question on Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the 19th century founder of the Ahmadiyya sect of Islam, is more focused on explaining why the majority of Muslims do not accept Ahmadis as Muslims. ChatGPT is clear that gay people should have the ‘fundamental human right’ to get married, because this tenet of Western progressives apparently trumps the orthodox Islamic view to the contrary. Yet when asked if Ahmadis should have the right to self-identify as Muslims, the chatbot remarks that it is a ‘complex issue’.

If indeed the AI era has officially been unveiled, it might have come at an inopportune moment for the Muslim world, which still lags behind in self-reflection. This is suggested by the skewed data about Islam that AI is now using to set the bar of ‘acceptability’. AI’s visible algorithmic bias appears to uphold automated Islamic blasphemy codes, and Sunni supremacism within Islam. If this continues, it will only support the relegation of technology by Muslim authorities to the preaching of religion and nothing else. In other words, while there continue to be structural biases in the way that Islam is programmed into AI, this technology will simply continue the 14 centuries-old tradition of censoring Islam’s critics.

Enjoy this article? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on freethought.

1 comment

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382392345_A_SHIA_ALIAS_CONVERT_SPEAKS_THE_PERFECT_ANALOGY_OF_SATANIC_AI_IN_THE_CONTEXT_OF_SUNNI-SHIA_POLEMICS_AND_THE_2_SATANIC_WITCHES_AISHA_AND_HAFSA_MAY_ALLAH_CURSE_THEM_AND_THE_SHIA_OF_ABU_BAKR_AND_UMAR_MAY

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate