‘Thought is free, or it isn’t thought.’

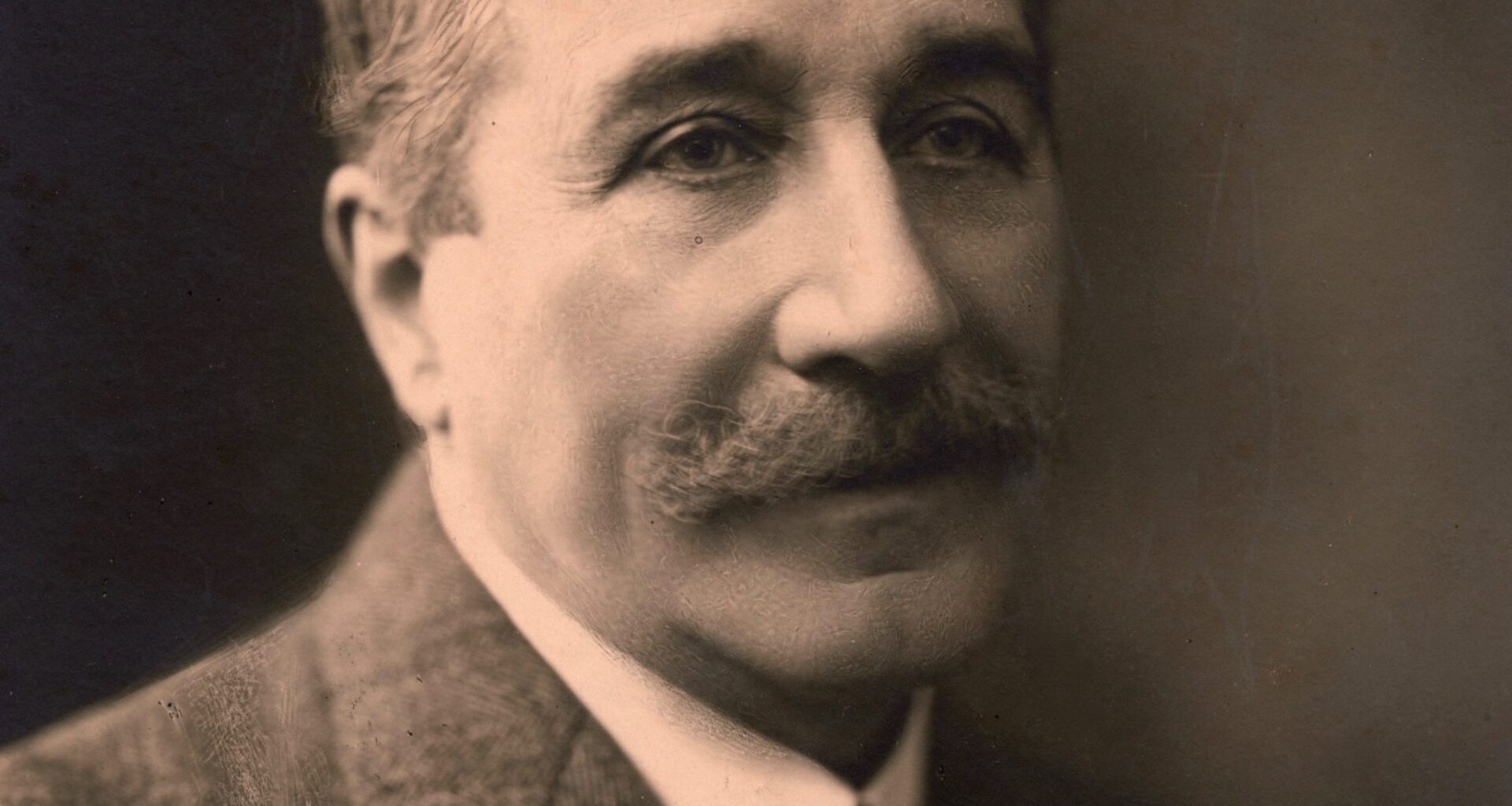

This fine remark comes from Emile Chartier (1868-1951), a French thinker, writer, teacher and humanist best known under his pseudonym, Alain. He was a prominent intellectual figure in the France of the 1930s, but is unfortunately little known in the Anglophone world, and sparsely translated into English. He remains one of the rare thinkers to make the bridge between philosophy and literature: ‘the finest prose of ideas of the century’, as the contemporary philosopher, André Comte-Sponville, has said.

Having trained as a philosopher and started a career as a teacher that would lead to the prestigious lycées of Paris, Alain began in 1903 to contribute short columns to a radical local newspaper in Normandy. From 1906, this became a daily exercise which he continued right up to the outbreak of the First World War, making a total of over three thousand pieces. He called these brief essays propos (not an easy word to translate, implying both ‘proposals’ and ‘remarks’). Their concise and vivid style soon attracted a loyal readership and they were collected into published volumes. The starting point was often a precise fact or event, something seen in the street or read in a newspaper; at first mainly comments on politics, their subject matter broadened to include philosophy, literature, education, nature, religion. He wrote, he said, to provoke his fellow citizens into thinking for themselves, to wake people up.

To return to the opening quotation, that thought is not thought unless it is free, this encapsulates a theme that runs throughout Alain’s work. As he wrote in his intellectual biography, Histoire de mes pensées (1936): ‘I’ve not reflected upon anything as much as freedom of judgement.’ What is it to think freely? He provided two lapidary definitions. ‘To think is to weigh’ – penser, c’est peser, almost a pun in French. The second is perhaps his best known quotation: ‘To think is to say no’ (penser, c’est dire non). The second half of this quotation is even better: ‘Note that the sign for “yes” is that of a person falling asleep; while to wake up is to shake the head and say no.’

‘The sign for “yes” is that of a person falling asleep; while to wake up is to shake the head and say no.’

~ Alain

To elaborate: ‘The problem is always the same, we have to control appearances, through the view of a free mind, which arouses and re-arouses doubt and proof together… we have to begin by not believing everything and so navigate the problem with our own strength alone, to find ourselves lost and abandoned as was always the case for a human being who rejects pious lies, and to recognise ourselves as completely deceived by appearances, and to save ourselves by the constructions of understanding alone.’ He also gives this definition of ‘mind’ (esprit): ‘at bottom the power of doubt, which is to raise oneself above all mechanisms, order, virtues, duties, dogmas, to judge them, subordinate them, and replace them by freedom, which only owes anything to itself.’ This link between the freedom of the mind and the freedom of the individual can be seen as a precursor to the existentialism of the 1940s associated with Sartre, de Beauvoir and Camus.

I have hinted at the variety of Alain’s interests. His propos, which he continued after the war, have been gathered into many published collections, the best known of which is Propos sur le Bonheur (one of the very few books of his to be translated into English, as Alain on Happiness). He also wrote major philosophical works after the war. He is probably best known in France for his views on politics; he also developed sophisticated theories of perception and the imagination, but for the remainder of this article I shall focus on his humanism and views on religion.

As a thinker who avoided labels, Alain did not call himself a humanist as such. A label is a summary that must always leave something out. But it is clear enough that he is very close to it, in this definition: ‘the aim of humanism is freedom in the full sense of the word, which depends above all on a bold judgement against appearances and seductions… Humanism always aims at increasing everyone’s real power, through the widest culture – scientific, aesthetic, ethical. And a humanist recognises as precious in the world only human culture, through the outstanding works of all periods.’ We can see in this description the activity of the teacher he was, and remained in his writing. The ‘widest culture’: in his philosophy classes, as well as Plato, Descartes and Kant, he also taught Homer and Balzac; he wrote books on Balzac, Stendhal and Dickens, and commented on the poems of Paul Valéry, as well as on the arts in general – the humanities, as he preferred to call them. Humanity lives in its works and that is where to seek it out: ‘human works, mirrors of the soul.’

‘The aim of humanism is freedom in the full sense of the word.’

~ Alain

Another area of humanity’s manifestations is its festivals, like Christmas and Easter. Alain reminded his readers that these are essentially pagan festivals which link us to nature and are, at the same time, powerful symbols and expressions of human feelings. Christmas promises rebirth, of which a newborn child is an image. Or, in another propos: ‘the images of Christmas are astonishing and even, when looked at closely, subversive. The child in a crib, between the ox and the ass, with the adoring kings from the Orient, this means that power isn’t worth a single grain of respect.’ Easter is resurrection of the earth. All Souls’ Day ‘falls where it should, when the visible signs make it quite clear that the sun is abandoning us…There is harmony between customs, the weather, the time of year and the course of our thoughts.’

Alain remained firmly anticlerical all his life. In fact, in 1897 he managed to earn a headline in a local Catholic paper in one of his first teaching posts, after casting doubt on the existence of the devil and hell in a public lecture. The newspaper assured him, ‘No offence to the young man teaching philosophy in the lycée: Hell exists.’ Parents were advised to withdraw their children from his lessons. Yet he recognised that religions, like festivals, are also human constructions and activities. An anecdote he often recounted is that of being asked by a fellow soldier during the war, who had noticed that Alain was a non-believer, what he thought of religion. ‘It’s a story,’ he replied, ‘a fairy tale, which like all stories is full of meaning. No one asks whether a story is true.’

Alain’s meditations on religion culminated in a work published in 1934, Les Dieux, translated into English in 1974 as The Gods. Religious stories and practices, he argues, ‘are not facts, but thoughts.’ They express truths more vividly than theoretical and theological statements. Likewise, the gods themselves are human creations. ‘The gods refuse to appear and it’s through this miracle that never occurs that religion develops into temples, statues and sacrifices.’ And again, ‘the gods are our metaphors, and our metaphors are our thoughts’. There is no transcendence. There is nothing behind the signs and metaphors. All the mystery is man-made.

‘[Religion] is a story, a fairy tale, which like all stories is full of meaning. No one asks whether a story is true.’

~ Alain

A further implication is that factual and historical questions are rejected. It does not matter whether Christ existed or not, whether he said this or that, here or there. The Gospels are less a historical record than like a great work of art that continues to speak to us. What matters is the truth in the story. When Jesus attacks the Pharisees in Matthew 23, for their shows of religion and their hypocrisy, what matters is whether what he says of them applies to some human beings, which might even include oneself. To ask whether Jesus actually said these words is to postpone that self-examination. In short, it is the morality taught by religion, explicitly and implicitly, that is important. ‘It is never the dogma that proves the morality; morality, as far as I understand it, supports itself; God adds nothing; paradise, hell, purgatory add nothing.’

The Gods also has a classification of religions, drawing on Hegel and Auguste Comte, which presents Christianity as a development of pagan religion, and an improvement in that it rejected sacrifices and oracles. It made everyone, slaves included, brothers and sisters. Alain liked to quote an anecdote from Chateaubriand’s Les Martyres. A pagan and a Christian meet a poor man. The Christian gives him his cloak. The pagan, knowing that the gods sometimes visited in the shape of a human being, says ‘No doubt you thought it was a god’. – ‘No’, replied the Christian, ‘I simply thought he was a man.’

For Alain, Christ appears as a new god who is human, who has lived the life of human beings, who was ‘weak, crucified, humiliated’ and who rejected power and force. He represents the free mind which is the final judge of all power, though the church, unfortunately, has always tended to associate itself with power. ‘The meaning of the cross is that the highest model of man lived poor and scorned by the great and that he died, punished for his virtues which denied ambition, desire, evil. It was a miserable fate, ennobled by thought, ended by an executioner.’

It is an interpretation of Christianity that leaves out the unrelenting god of the Old Testament. Stripped away are beliefs in miracles, in life after death, in divinely revealed truth, in original sin and redemption through sacrifice. There is also a refreshing avoidance of arguments about the existence or non-existence of god. (In fact, Alain has an argument that existence is not susceptible of proof.) To put it briefly, he interprets Christianity as a humanist religion.

This article can only give a taste of the richness of Alain’s writings, which are concerned with what it is to be a human being. How should we live? How should we live together? These questions do not age.

Find out more

There is an excellent website dedicated to Alain’s work https://philosophe-alain.fr/ Most of the material is in French, but there is also some English content: translations and a handful of articles, including a longer treatment of his discussion of religion.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate