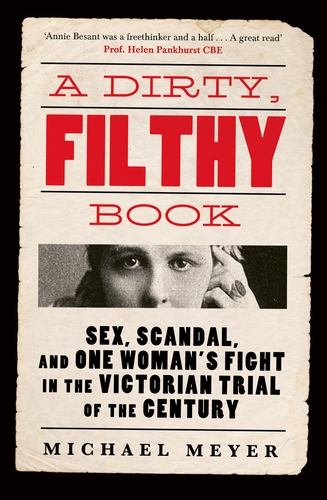

Michael Meyer has produced this splendidly researched and written account of the 1877 trial of Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant for republishing the American doctor Charles Knowlton’s infamous birth control pamphlet The Fruits of Philosophy (1832).

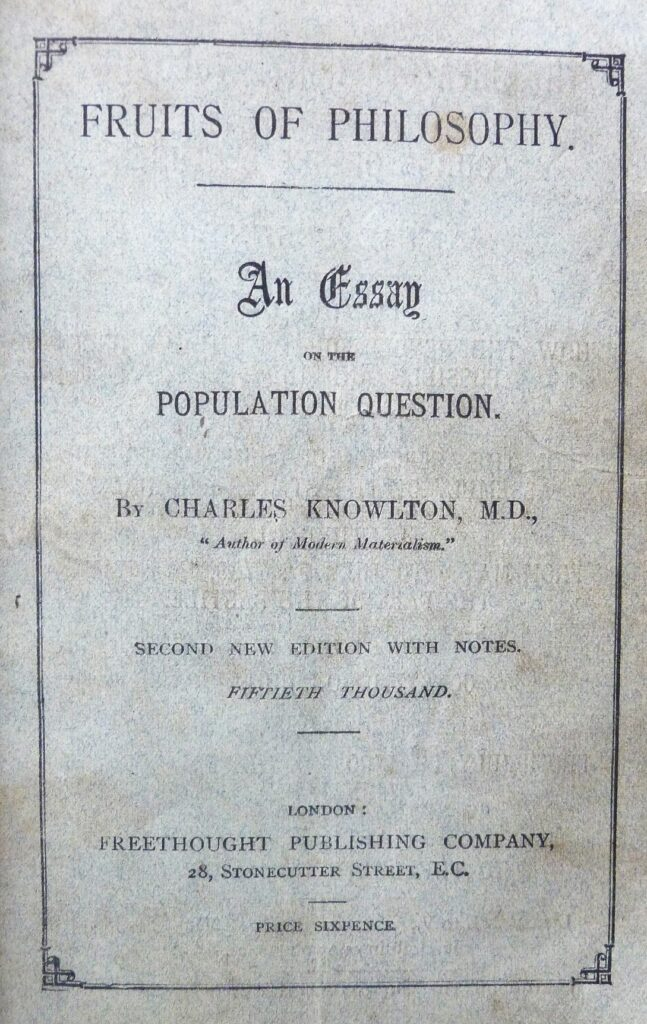

This pamphlet was the most influential nineteenth-century tract of its type. It provided cheap but useful advice on how to prevent conception. Within months, a British edition appeared, published by a succession of freethought publishers. By 1876, the plates were in the hands of Charles Watts, then secretary of the National Secular Society (NSS) and a close ally of the NSS’s President, Charles Bradlaugh, and one of its Vice-Presidents, Annie Besant. The pamphlet had been selling steadily but in small numbers, perhaps 700 per annum. In 1876, a Bristol bookseller, Henry Cook, was sentenced to two years’ hard labour for selling the pamphlet adorned with ‘obscene’ illustrations. We can only guess how ‘obscene’ these were, as no illustrated copies survive. Now, with their appetites whetted, the authorities decided to press on and prosecute the publisher, Charles Watts. To the extreme disgust and fury of Bradlaugh and Besant, Watts pled guilty to publishing an obscene book and was let off with a suspended sentence.

Meyer argues that it was Besant who showed the greater resolve and persuaded Bradlaugh that the booklet was defensible. Others have argued that Bradlaugh needed no such persuasion. In any event, the pair broke all connection with Watts and determined to republish the tract, with new medical notes, themselves. For this purpose, they founded the Freethought Publishing Company, taking out a lease on a small shop close to Fleet Street.

On the day the pamphlet went on sale, there were crowds in the street when the shop opened. Bradlaugh and Besant were both there and 500 copies exchanged hands in the first twenty minutes, with 125,000 sold in the first three months. Bradlaugh and Besant made no secret of their activities and were duly prosecuted. The importance of the case was underlined by the appearance of the Solicitor General, Hardinge Giffard, as chief counsel for the prosecution. Bradlaugh and Besant defended themselves with skill and passion. Regarding Besant, it was virtually unheard of for a woman, and a young woman at that, to represent herself, but Besant did so without hesitation. The arguments used by the pair were wide-ranging, but a common theme was that they were representatives of a morality superior to that of their persecutors. This was not to deter their opponent Giffard, who uttered the following words in his summing up:

‘I say this is a dirty, filthy book, and the test of it is that no human being would allow that book to lie on his table; no decently educated English husband would allow even his wife to have it…’

Despite the judge, Sir Alexander Cockburn, summing up in terms favourable to the defendants, the jury returned an ambiguous verdict, concluding that although the book was calculated to deprave public morals, they could not find that the defendants had corrupt motives. A perplexed Cockburn interpreted this as a guilty verdict but the defendants appealed and succeeded in having their conviction overturned on technical grounds.

Although the trial is Meyer’s main focus, he also goes much deeper. He explains the backgrounds of both Bradlaugh and Besant and shows how they came to hold their opinions. He also explores the consequences of their actions for themselves. For example, and tragically, Annie Besant was to lose custody of her daughter, Mabel, in 1878, having been deemed an unfit mother. Custody passed to her husband the Reverend Frank Besant, from whom she was estranged and whom she loathed. The consequences for Bradlaugh were not quite so drastic, but Meyer describes his subsequent struggle to be elected an MP and then take his seat. He was prevented from doing so by religious opponents incensed by his atheism and what they saw as his associated low morality. Such contextualisation is further provided by periodic references to events in wider society relevant to public and establishment attitudes to birth control.

For Meyer, the life and career of the extraordinary Annie Besant is central to his narrative. Her vitality, courage, energy, and sparkling intelligence are nothing if not inspirational and he is astonished that she is not better known and celebrated. Of this, I am unconvinced. There have been several biographies, the best of which is Arthur H. Nethercot’s superb two-volume account, although this dates from the early 1960s. She also often takes a place of honour within the many books charting the history of the birth control movement. Annie was associated with other vitally important events and ideas in radical and working-class history, including her pioneering feminist writings and her support of the Bryant & May matchgirls’ strike of 1888. However, by the late 1880s, she was moving away from organised freethought and from Bradlaugh, embracing first socialism and then theosophy. For the first, she could be forgiven and accommodated, but not for the second.

Still, it is true that she was ultimately seen as having betrayed her secularist comrades, who would undoubtedly have relished celebrating her achievements more had she stayed within the fold. She would also almost certainly have succeeded Bradlaugh as NSS president upon his untimely death in 1891. Her former friends watched her go with sadness rather than rancour, but sadness is not the positive emotion that provides a good basis for celebration. Perhaps it is strange that the Labour Party has not had more to say about her, particularly as she passed through a Fabian and socialist stage. But the Labour Party has never shown great affection for freethinkers, generally favouring its non-conformist and Christian socialist roots. Besant spent the second half of her long life in India, where she is better remembered for her championing of Indian nationalism.

By focusing on Annie Besant, Meyer may be responsible for failing to fully recognise the role and significance of her mentor, colleague, and confidant, Charles Bradlaugh. For example, although Besant’s role in the Knowlton trial was spectacular, it was Bradlaugh’s extraordinary self-taught legal knowledge that guided them and made their defence possible. And, though the consequences were dire for Besant, Bradlaugh had to suffer the anguish of a six-year struggle to take his rightful seat as an MP, facing deliberate efforts to bankrupt him through prosecutions designed to result in huge financial penalties. His daughter and disciple, Hypatia, always argued that it was this struggle that contributed to his early death in 1891. Unlike Besant, Bradlaugh remained steadfast and consistent in his opinions, and it is symbolic that Bradlaugh’s grave and monument at Brookwood is surrounded by those of his fellow birth control pioneers and freethinkers while Annie was cremated on a different continent.

The Knowlton case was significant for other reasons too. Central were the issues of freedom of speech and bodily autonomy; the trial’s outcome represented a significant victory on both counts. This battle goes on, is never won, and remains central to the freethinking, secularist tradition. As for the birth control movement, it would be nice to assume that prosecutions ceased, but they did not. Booksellers continued to serve prison sentences and have stock seized. The year after the Knowlton trial, Edward Truelove, the veteran freethinking publisher, was imprisoned for four months in London’s grim Coldbath Gaol for publishing Robert Dale Owen’s Moral Physiology, a work generally regarded as milder than Knowlton’s. But perhaps these prosecutions were final, futile attempts to resist change. I am sure Meyer is correct when he writes of the case as a ‘quantum leap’ which ‘[legitimised] contraception as worthy of public discussion, and [as something that was] morally permissible to practise at home.’ That was some achievement.

A Dirty, Filthy Book is a superbly written model for those who aspire to write significant but accessible history. Perhaps this is only to be expected from such an experienced journalist and author whose main academic post is as a Professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh. The book fizzes along and deserves a bumper sale. It also partly provides something desperately lacking— a highly readable history of the National Secular Society, founded in 1866, the UK’s oldest extant radical campaigning pressure group.

Of course, it only deals with what might be termed the ‘heroic’ phase from 1866 until Bradlaugh’s death in 1891, but it is welcome for all that, leaving just 134 years to cover for some other enterprising writer. The individualistic, intellectual tradition represented by organised freethought and secularism has been deficient when it comes to recording its own history and substantial achievements—a marked contrast with the churches, who wallow in their perceived past glories. Most of what has been written about secularism is to be found in academic treatises, worthy in their way, but unappealing to the general reader. Michael Meyer’s book is a sparkling exception and I, for one, am grateful for this.

A Dirty, Filthy Book can be purchased here. Note that, when you use this link to purchase the book, we earn from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate.

Further reading

Freethought and birth control: the untold story of a Victorian book depot, by Bob Forder

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate