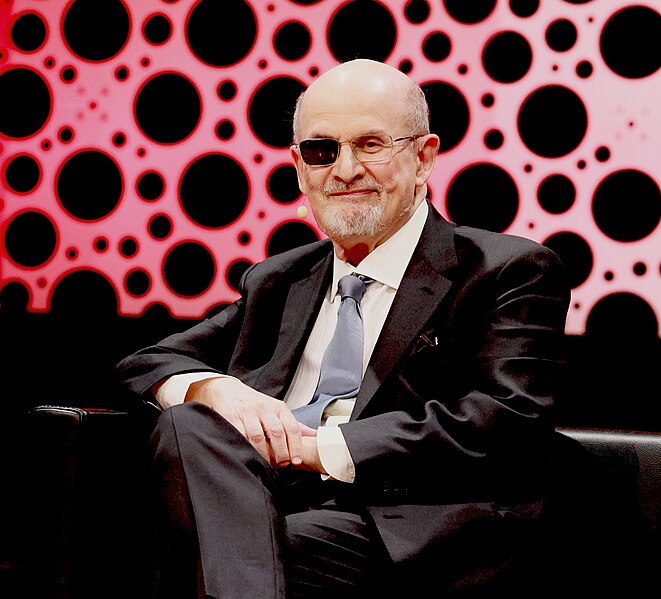

‘What you have made will long endure.’ This is how Salman Rushdie signed off one of his last emails to his friend Martin Amis. Amis was dying from oesophageal cancer (the same cancer that killed his and Rushdie’s old comrade Christopher Hitchens) and Rushdie was still recovering from the savage attack against him in Chautauqua, New York when those words were written. Amis had previously written to Rushdie, of seeing him for the first time since the attack, that ‘I expected you to be altered, diminished in some way. Not a bit of it: you were and are intact and entire. And I thought with amazement, He’s EQUAL to it.’

Simple expressions of love and solidarity between two men all too well acquainted with the destroying angel: the perfect riposte to death, and to the bigotry and fanaticism of those, like Rushdie’s attacker, who worship it. This is just one of many life-affirming moments in Rushdie’s account of what Amis so appropriately calls ‘the atrocity’ of August 2022 and its aftermath, Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder. Like the late Amis (who died last May), what Rushdie has made will long endure. His contributions to literature will endure for their power and beauty and truth, not because of the horrors inflicted upon their author. Still, and though he would prefer not to be defined by those horrors, his courage and his unswerving commitment to the defence of free expression in the face of them—this example, too, will long endure.

In August 2022, on the very day of the atrocity, I wrote a response, concluding with these words: ‘Pull through, Salman. Pull through.’ And pull through he did. He was equal to it, all right. The sheer strength of the man is nothing less than astounding: a 74-year-old asthmatic, who had endured through a COVID-19 infection, is stabbed and slashed over and over by a would-be assassin, and he pulls through, even though the doctors thought his survival a near-impossibility. No, he more than pulled through: he won. He has lost an eye and suffered horrifically, but his mind remains, and he has written a brave and beautiful book to ‘answer violence with art.’

‘I wasn’t well enough to take in clearly the scale of what was happening outside my hospital room, but I felt it,’ Rushdie writes of the thousands of outpourings of solidarity he received. ‘I have always believed that love is a force, that in its most potent form it can move mountains. It can change the world.’ It is heartening to know that the tsunami of love heartened Rushdie in his hospital bed; whether or not he knew of my own outpouring I do not know, but it is nice to think of it as a small undulation in the tsunami.

Knife is not just a personal narrative. It is also a reaffirmation of Rushdie’s commitment to the fight for ‘the idea of freedom—Thomas Paine’s idea, the Enlightenment idea, John Stuart Mill’s idea’ against its many enemies, whether left or right, progressive or reactionary. He also reaffirms his secularism and his atheism: ‘My godlessness remains intact. That isn’t going to change in this second-chance life.’

But the genius of the book is that it is not a horror story, or not merely a horror story. It is, ultimately, a love story. Rushdie tells us how he met and fell in love with the American poet and novelist Rachel Eliza Griffiths, whom he married in 2021, and how Griffiths helped him through the horror: ‘The woman I loved and who loved me was by my side. We would win this battle. I would live.’

As against this, Rushdie’s attacker is not named at all. He is referred to only as ‘the A.’, ‘[m]y Assailant, my would-be Assassin, the Asinine man who made Assumptions about me, and with whom I had a near-lethal Assignation . . .’ In one powerful chapter, Rushdie imagines a conversation between himself and the A., and the A. is revealed as the nameless loser he undoubtedly is. Later, Rushdie tells us what he would like to say to the A. in court, and he concludes that:

‘Your intrusion into my life was violent and damaging, but now my life has resumed, and it is a life filled with love… I don’t forgive you. I don’t not forgive you. You are simply irrelevant to me. And from now on, for the rest of your days, you will be irrelevant to everyone else. I’m glad I have my life, and not yours. And my life will go on.’

But Rushdie also tells us that he no longer really cares about getting to face his attacker; the A. truly has become irrelevant. And life and love go on: ‘After the angel of death, the angel of life.’

Like Rushdie’s latest novel Victory City, Knife is a humanist triumph. Referring to the former, I wrote that ‘Rushdie shows us the triumph of love, life and literature against philistinism, death and fanaticism.’ And so he continues to do. Knife, despite it all, has a happy ending. Rushdie and Griffiths return to the scene of the crime, more than a year later, and Rushdie realises his triumph:

‘Yes, we had reconstructed our happiness, even if imperfectly. Even on this blue-sky day, I knew it was not the cloudless thing we had known before. It was a wounded happiness, and there was, and perhaps always would be, a shadow in the corner of it. But it was a strong happiness nevertheless, and as we embraced, I knew it would be enough.’

In Knife, Salman Rushdie shows us that he has lost none of his power. The horror is subsumed and conquered by love. It is a work of genius, another testament, like his memoir Joseph Anton, to what Rushdie has called ‘the liberty instinct’: the indestructible human desire for freedom. In the end, Knife is Rushdie’s greatest victory.

Knife can be purchased here. Note that, when you use this link to purchase the book, we earn from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate.

Further reading

The Satanic Verses; free speech in the Freethinker, a compendium of relevant articles by Emma Park

The need to rekindle irreverence for Islam in Muslim thought, by Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

‘Nature is super enough, thank you very much!’: interview with Frank Turner, by Daniel James Sharp

1 comment

Review of Rushdie’s Knife

Sharp, Daniel James, “Rushdie’s victory,” in: The Freethinker, April 22, 2024: https://freethinker.co.uk/2024/04/rushdies-victory/

“Knife is not just a personal narrative. It is also a reaffirmation of Rushdie’s commitment to the fight for ‘the idea of freedom-Thomas Paine’s idea, the Enlightenment idea, John Stuart Mill’s idea’ against its many enemies, whether left or right, progressive or reactionary. He also reaffirms his secularism and his atheism: ‘My godlessness remains intact. That isn’t going to change in this second-chance life.'” What Sharp writes here is all true.

Also, Sharp writes: “In one powerful chapter, Rushdie imagines a conversation between himself and the A., and the A. is revealed as the nameless loser he undoubtedly is.” Here I would give a slightly different answer. After all A. as a person is probably a loser. As a person, he will probably be sentenced to a long custodial sentence. But as a type, as a representative of jihadist Islam, he is not a “loser” at all. Rather, as a type, he is a “winner.” At least for now. Liberal-democratic states have not, for now, been able to find a solution in effectively defusing the individuals and ideologies that bury these societies. As a militantly aggressive ideology, jihadist Islam has proven very effective. Again: for the time being.

Rushdie, however, sees it as follows in the quote quoted by Sharp: “You are simply irrelevant to me. And from now on, for the rest of your days, you will be irrelevant to everyone else. I’m glad I have my life, and not yours. And my life will go on.'”

Again, that’s all accurate from Rushde’s perspective personally, but as a society, we are not at all done with “A.” And, if you think about that a little longer, even Rushdie is not done with “A.” After all, “A.” may soon be in prison, but “A.” has many friends who are in competition in exactly the same way as “A.”. Perhaps more friends than Rushdie has. For Rushdie’s friends are perhaps a dying group. Hitchens is dead. Not by a jihadist, but by cancer. As is Martin Amis. But many contemporary literary writers are politically correct or woke to the bone. Who, like Matar, wonder: why so provocative? Didn’t Rushdie bring it all on himself?

Sharp follows Rushie in Rushie’s view of himself. Sharp writes: “Like Rushdie’s latest novel Victory City, Knife is a humanist triumph.” Is it? Has humanism triumphed here? Or, on the contrary, does humanism as a social phenomenon prove weak in the face of the forces that seek to destroy it?

Further, “In the end, Knife is Rushdie’s greatest victory.”

Yes, in the sense that Rushdie as an individual proved himself capable of going on with his life and continuing to write.

But no, because the actual subject that hangs over Knife like a dark cloud, the power and threat of radical Islam, feels it must remain silent.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate