I was born to an Indian Bengali Hindu family. My childhood was drenched in the rich embroidery of customs, ceremonies, and convictions; my perspective was moulded by the strict social standards that were imposed upon me. But I ended up scrutinising the doctrines that characterised my reality, and now I consider myself a seeker of truth rather than a follower of custom. I have travelled from unbridled religiosity to reasonableness.

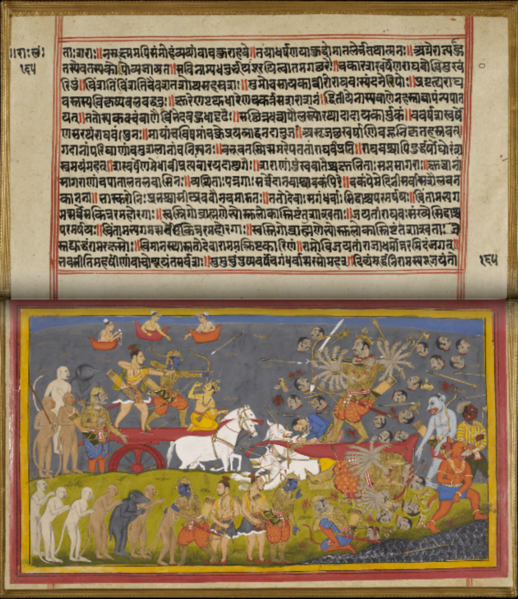

My childhood in a Hindu family imparted to me a profound veneration for the heavenly. Narratives of divine beings were woven into the texture of my life. I believed in a world full of divine powers. My grandmother used to recount these exciting stories to me, from Prince Rama killing the demon Ravana and winning the beautiful Sita back to how Narasimha (an exceptional blend of human and lion and the fourth avatar of Vishnu) killed the evil king Hiranyakashipu and protected the king’s faithful son Prahlada.

However, as I grew up, I started to understand that these stories were simple legends. The seeds of uncertainty were planted in me as I took note of the irregularities and inconsistencies of the holy texts and lessons that I had once accepted unquestioningly. Questions emerged: How could a considerate god support unfairness and suffering? What objective reason was there for considering some practices sacrosanct and others not? Why should a husband be seen as a god by his wife? Why should the wife not be treated equally?

These and many other questions drove me to investigate what I had been taught, and eventually I broke free from the shackles of religiosity that had been imposed on me from birth. This was an overwhelming experience of liberation, but it caused conflict between me and my family and others who lived nearby. They could not let go of dogma and custom and were unable to engage with different viewpoints. My family made me practice absurd rituals like not oiling or shampooing my hair, not cutting my nails, and not having non-vegetable foods for 13 days between my grandmother’s death and funeral. But I was undaunted, still desperate to find my own way based on reason and evidence rather than blind adherence to antiquated traditions.

The situation between me and my family was like a cold war initially, but as time went on, they realised that forcing me to adhere to dogmas would not only hamper my personal growth but strain my relationship with them. With time, we both understood that to maintain a healthy relationship, we had to desist from discussing religion openly and respect each other’s choices.

The Hindu misogyny I experienced played a major role in my rejection of dogma. Disallowing menstruating women from entering temples, decreeing that widows are not allowed to participate in wedding rituals, preventing infertile women from taking part in baby showers, and various other misogynistic practices emboldened me to raise my voice against injustice.

I decided to embrace sanity. I recognised that the world was not generally as it appeared and that the search for truth was a progressive and always-evolving endeavour. Many books helped me in my journey towards rationality, starting with the Indian revolutionary Bhagat Singh’s 1930 Why I Am an Atheist, which Singh wrote in jail just months before his execution. Singh left certain logical questions—like ‘Why doesn’t God create a better world for humans?’ and ‘Why doesn’t God stop humans from committing sin?’—unanswered in my mind. Later, books like The God Delusion (2006) by Richard Dawkins, God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (2007) by Christopher Hitchens, and Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (2006) by Daniel Dennett helped me in my path to enlightenment.

So far, my experience as a secular person has been exciting, diverse, and full of challenges. On the one hand, I have faced questioning and judgement from people opposed to my views, and on the other, I have found comfort and backing in networks of similar people who shared my feelings and gave me a sense of fellowship that rose above the limits of religion, nationality, and culture. As I continued my journey, I felt I was in the right kind of company.

As I look back, I feel great appreciation for all the encounters I have had, both positive and negative, for they have moulded me into the person I am today. While the journey to reason was full of difficulties, it was also full of epiphanies, understanding, and personal development. Each step forward gives me a more profound knowledge of myself and the world I find myself in. It has provoked me to scrutinise the convictions and suspicions that once characterised my reality and to embrace vulnerability and uncertainty with boldness and interest. As I continue to explore the intricacies of life, I’m inspired by the thought that the pursuit of truth is an undertaking motivated by our most elevated desires, and I know that by rocking the boat and thinking freely we can make ourselves, and our world, a happier and better place.

Related reading

Religion and the decline of freethought in South Asia, by Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

The rise and fall of god(s) in Indian politics: Modi’s setback, Indic philosophy, and the freethought paradox, by Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

Image of the week: Ajita Kesakambali, ancient Indian materialist and one of the Six Heretics, by Daniel James Sharp

Campaign ‘to unite India and save its secular soul’, by Puja Bhattacharjee

The resurgence of enlightenment in southern India: interview with Bhavan Rajagopalan, by Emma Park

‘We need to move from identity politics to a politics of solidarity’ – interview with Pragna Patel, by Emma Park

2 comments

This article is a triumph of reason and intellect. You should be incredibly proud of yourself.

More Power to you Amrita!

Thank You so much!

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate