Myth? Legend? Folklore? History? Fiction? This is The Story of Russia, as the title of Orlando Figes’s 2022 book puts it.

Every nation, every country, and, indeed, every empire has a founding myth: some event or figure that is meant to embody the values and origins of the state and unify the people with an overarching narrative of where they came from and where they are going. Figes shows, however, that Russia is a peculiar exception to this norm. For many reasons, when it comes to Russia’s history and origins, there is no true consensus or understanding. Rather, Russia’s history and origins are so deeply intertwined with myths, narratives, legends, politics, folklore, and religion that you must first be willing to dive deeply into all these intricate components and then sift through them to discover even a morsel of truth.

As Figes demonstrates in his work, despotism is one constant truth of Russia over 800 years, from the authoritarianism of Kievan Rus’ (the progenitor of modern Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus) to Putinism. The systems and titles may have changed several times, but the brutal and violent methods of securing and maintaining centralised power in Russia have remained largely unaltered—because, circularly, the belief that Russia can only be ruled by brutality and violence has remained largely unaltered as well.

Russian industrialisation did not even begin until the late 19th century, partially because of Russia’s reliance on serf labour. Because serfs had no social or economic mobility, and even their physical mobility was restricted to the confines of their village, there was no space for innovators, investors, and entrepreneurs who could revolutionise the system. The natural emergence of capitalism, inextricably connected to industrialisation (like an axle to a wheel), was impossible for a long time in Russia. In Russia, unlike the rest of Europe, the state, in the form of the Tsar, was the sole financier of industrialisation.

During the first half of the 18th century, the skill of history writing was still emerging in Russia. A German scholar named Gerhard Friedrich Müller outraged the Russian academics at the newly established St Petersburg Academy of Sciences by daring to conclude, based on his research of the Primary Chronicle, that Russia’s origins could be traced back to the Vikings. To say that Scandinavians created Russia was not something to be lightly asserted at a time when Russia had just emerged from victory in one of its many wars with Sweden!

Müller was accused by Mikhail Lomonosov, his rival in the academy, of degrading the Slavs by presenting them as savages who couldn’t organise their state without outside help. The Russians, according to Lomonosov, were not Vikings, but Baltic Slavs, descendants of the Iranian Roxolani people, whose history dates back into the mists of antiquity.

Another fascinating aspect of Russian history that Figes delves into is the notion of Moscow as the ‘Third Rome’, the bearer of the Orthodox Christian flame after the fall of the ‘Second Rome’, Byzantium. This succession—or natural inheritance, as it is viewed by many Russians—means that Russia has a God-given mission in the world, a view that derives in part from the medieval theology it inherited from the Byzantines. The idea that the West is in a state of degeneration and collapse and that Russia is a superior civilisation thanks to its unbending devotion to Orthodoxy is an idea that has recurred again and again in Russian history. Holy Russia, in short, is the true source of humanity’s salvation. This view of Russia as saviour fundamentally influenced both the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. The sacralisation of power was deeply linked to this because it portrayed the Tsar (or the Party) as the direct manifestation of God’s will on Earth (or the embodiment of the dialectic of history).

This messianic streak is still apparent. Putin’s ongoing war with Ukraine can be understood through this framework: divine right places Putin above human laws, human rights, and earthly realities, and Ukraine, due to its exposure to the degenerate societies of the West, is in need of cleansing by holy war.

Figes skilfully examines the reasons behind Russia’s failure to establish a democratic government over the centuries (contrast with Ukraine) by compellingly illustrating how democratic reforms were consistently hindered by pivotal historical events. These events include the impact of the French Revolution during Catherine the Great’s reign, Napoleon’s invasion of Russia during Alexander I’s rule, the assassination of Alexander II in 1881 (which halted his transformative reforms), the suppression of democratic ideals by the Bolsheviks after the 1917 revolution, and the perpetuation of autocratic tendencies following the fall of the Soviet Union. While Western thinkers have debated, discussed, and theorised about the abstract notions of the state and the people, the role of religion, and the role and structure of the state for hundreds of years, there has been no similar wide-ranging, long-term enquiry in Russia.

Where is the holding to account for the cultural genocide, forced assimilation, brutal treatment, and forced imprisonment of indigenous peoples in and along the eastern portion of Eurasia?

Yet another fascinating and critical topic explored in The Story of Russia is Russia’s eastward expansion. As Figes notes, between 1500 and 1917, the territories controlled by the Russian state grew, on average, by a staggering 1,300 square kilometres per day. This expansion, of course, was not merely of land; it also included expansion of control over the indigenous populations the Russians encountered. Russian expansion was, in essence, Russian colonialism. However, unlike in many Western countries, Russia has not reflected on or reckoned with its colonial past. Russian expansion is viewed as a kind of ‘self-discovery’—or, as Figes describes it, as the story of a country colonising itself.

It is certainly not shocking that no such reckoning has occurred or even begun in Russia given that the official narrative on all matters Russian has been crafted by authoritarian regimes, from the Tsars and the Soviets to Putin. But where, then, is the international community? Where are the protests against the bloody past, so common in the West? Where is the holding to account for the cultural genocide, forced assimilation, brutal treatment, and forced imprisonment of indigenous peoples in and along the eastern portion of Eurasia?

Perhaps the only apt comparison is that of the plight of the Uyghur Muslims, a Turkic-speaking ethnic group who live in the northwestern region of Xinjiang, China. Over one million Uyghur Muslims have been imprisoned by the Chinese government since 2017, and those not imprisoned are subjected to intense surveillance, religious restrictions, forced labour, and forced sterilisation. The outcry, protests, and condemnation from the international community on this issue have also been lacking, albeit not totally absent. Similarly, but to a worse extent, the silence on the ongoing plight of the indigenous peoples of Russia is stunning.

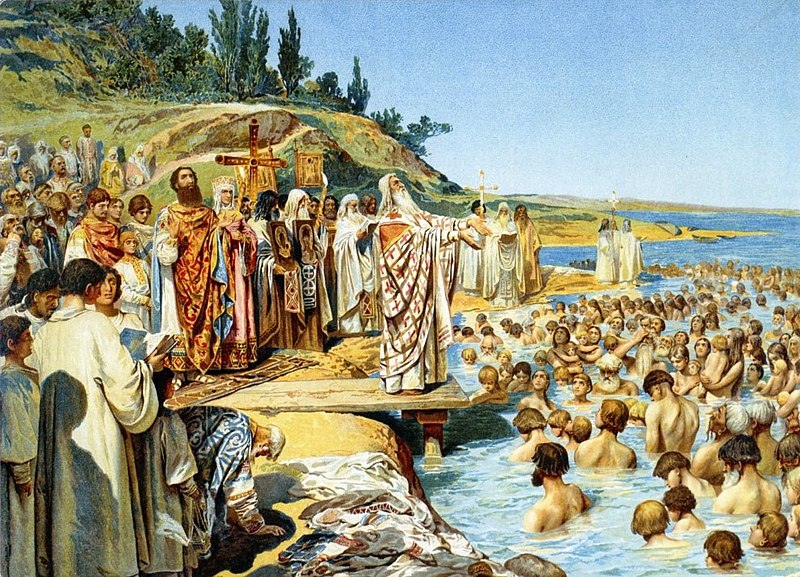

Figes’s assessment of the Putin regime’s endorsement of the doctrine called the ‘Russian World’ is particularly valuable. According to this doctrine, Russia is a civilisation characterised by its spiritual values, in contrast to what is perceived as the liberalism and materialism of the West. The ‘Russian World’ includes not merely Russia, but also Ukraine and Belarus, a view supported by Patriarch Kirill, head of the Russian Orthodox Church, who believes that all Orthodox believers, whether in Russia, Ukraine, or Belarus, have a common origin and deep connection stemming from the coming of Christianity to Kievan Rus’ in 988. Kirill’s shocking inability to denounce Russia’s war on—not to mention his declaration of holy war against—Ukraine is a direct consequence of this view of history.

Among the many important themes discussed by Figes, one stands out to me as a necessary reminder of the malign uses to which prejudiced historical narratives can be put. That is, in true Orwellian fashion, control over how the past is understood grants control over the present and the future. The current unnecessary and unprovoked war with Ukraine is the result of Russia being detached from its history and at the mercy of an ever-changing narrative that benefits the ruling class and buttresses that class’s hold on power. This war is not just a crime against Ukraine, but also one against the best of Russia, whose literature and art have enriched Europe for centuries, and the people of Russia, whose desire for liberty has, tragically, never been fully realised. This war, in all its aspects, will only continue until and unless Russia is free to understand its own history—and learn from it.

Related reading

A view from Kyiv: Ordinary life during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, interview by Emma Park

Can the ‘New Theists’ save the West? by Matt Johnson

Against the ‘New Theism’, by Daniel James Sharp

What has Christianity to do with Western values? by Nick Cohen

Two types of ‘assimilation’: the US and China, by Grayson Slover

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate