One of the questions that has long troubled students of Buddhism is whether or not it should be considered a ‘religion’ on par with other world religions such as Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, etc. If, as adherents of the three Abrahamic religions believe, religion consists of belief in an almighty God who is the sole creator of the universe, then Buddhism is clearly not a religion, for Buddhism has no such belief. However, when looked at objectively, the question must be asked whether belief in a creator God is the sine qua non for determining what is and is not a religion. This leads to the larger question of how religion should be defined.

The Cambridge dictionary defines religion as: ‘the belief in and worship of a god or gods, or any such system of belief and worship’. Once again, measured by this yardstick, ‘godless’ Buddhism cannot be described as a religion. Nevertheless, if one were to walk into one of the many Buddhist temples scattered throughout Asia, one would encounter sacred altars, upon which one or more Buddhist statues are placed and to whom offerings of various kinds, from flowers to food, candles to incense, are made.

Once offerings have been made, rituals of various kinds are performed in front of these statues, typically beginning with either bows or full-body prostrations followed by the recitation of Buddhist sutras. After this, any number of ceremonies may be held: everything from wedding ceremonies to the far more numerous funeral services and associated ancestor rites. In short, Buddhist temples and the clerics that staff them engage in all of the religious activities typically found in any religious edifice throughout the world. Yet, all of this is done in the absence of a belief in God or gods. How is this possible?

The answer to this question requires that we travel back in time for tens of thousands of years, at least 70,000, and, most likely, far earlier than that, i.e., to the very origin of our own species—Homo sapiens. Scientists inform us that Homo sapiens emerged on our planet more than 200,000 years ago and likely as long as 300,000 years ago. Would our ancestors 200,000 years ago have had religion, or even needed religion? If so, why?

Admittedly, there is now no way to prove that religion existed 200,000 years ago, let alone what kind of religion it might have been. However, though still the subject of scholarly debate, there is recent research that suggests religious practices can be identified as far back as 70,000 years ago, i.e., dated back to rituals that were practised by peoples from the Middle Stone Age. Only the major findings of this research will be (broadly) discussed in this article; those who wish to delve into the details can find them here.

The key points are attested to by a cave in the Tsodilo Hills of the Kalahari Desert that has long been associated with ritual conduct. In short, what we find in this cave are all the elements that we today identify with animism, generally recognized as the oldest form of human religiosity. Animism is characterized by belief in gendered deities residing within natural objects who possess superhuman power and are thus able to bestow blessings—on the condition that proper ritual sacrifices are made to them. Such rituals are typically conducted by shamans and related figures believed to be able to communicate with the deities.

In addition, animism is characterised by an accompanying mythology that provides a framework for understanding life, nature, and the cosmos. In particular, multiple myths contain explanations for natural phenomena, such as why the sun rises, how seasons change, or why animals behave in certain ways. Tribal mythology also fosters a sense of kinship among tribal members and a connection with nature as a whole. By viewing animals, plants, and landscapes as living, spiritual beings, animistic myths encourage respectful and harmonious interactions with the environment. Finally, animistic myths convey moral lessons and ethical guidelines, teaching tribal members how they should behave towards each other as well as other beings, both seen and unseen. Like rituals, myths instructed people how they could connect with their deities for guidance, healing, and protection.

If many of the characteristics of animism seem similar to the major religions that exist today, there is nevertheless one very major difference. Namely, animistic religions were originally followed by, and exclusively for the benefit of, the people living in a particular tribe. Thus, just as the names of deities differed from one tribe to the next, so did their corresponding mythologies, not to mention the details of their rituals and ethical guidelines. In short, animism is originally a religion of, by, and for individual tribes that expressed itself in a variety of ways even while sharing an underlying unity. But this would change.

We are indebted to the 20th-century German philosopher Karl Jaspers for describing what he named the Axial Age, a period extending for some six hundred years from 800 to 200 BCE. Jaspers noted that it was during this period that religious leaders and philosophers across the world, from Confucius in China, the Buddha in India, Socrates in Greece, and later Hebrew prophets like Jeremiah and Deutero-Isaiah, were independently and nearly simultaneously adopting new ways of thinking that would shape the spiritual and philosophical foundations of many civilisations and religions.

All of these figures searched for universal principles that could apply to all people, regardless of tribal affiliation. This included the transition of tribal gods into universal gods, including the emergence of a belief in a single universal God. Standards of ethical and moral conduct were no longer limited to fellow tribal members but became universally applicable. That is to say, no longer was ‘anything goes’ acceptable in terms of the way one should treat ‘others’ if they were members of another tribe or nascent nation. In short, the ‘other’ was recognized as a fellow human being.

Further, tribal mythology was no longer deemed sufficient to describe the complexities of life. Instead, the search began for rational explanations for what had heretofore been seen as supernatural events, e.g., an eclipse of the sun. This led to the challenging of existing social norms and the examination of the nature of reality, not to mention the meaning of life. These thinkers sought to discover universal principles that would apply to all people regardless of tribe.

Yet, if the Axial Age can be said to have laid the groundwork for the philosophical, religious, and ethical systems we have today, it is critically important to realize that these insights, considered to be universal in nature, did not immediately transform the tribal-centric animistic religions that had been followed for thousands, if not tens of thousands, of years. In particular, even when religious leaders attempted to physically destroy or replace all traces of animism around them, they were not always successful. When the hold of animistic practices was too strong to be eliminated, or eliminated completely, the practices were often disguised and made to appear to be an integral part of the emerging universal religions.

Christianity

For example, what is today the most widespread Christian celebration of all, i.e., Christmas, has its roots in Roman-era animism. That is to say, the Roman festival of Sol Invictus, celebrated on 25 December, was the birthday of the god of the sun. It marked the rebirth of the sun as days began to lengthen after the winter solstice. In addition, a popular Roman festival held from 17-23 December celebrated Saturn, the god of agriculture, with feasting, gift-giving, and merrymaking. Since the Christian Bible said nothing about the date on which Jesus was born, Christians in Rome saw an opportunity to change popular animistic celebrations into a Christian celebration. Instead of destroying animistic festivals, Christians absorbed these festivals, though they were careful to hide the animistic origins from future generations.

Easter, the most important celebration in the Christian calendar, was also deeply influenced by animism. The very name ‘Easter’ is believed to have been derived from Eostre or Ostara, the Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring, dawn, and fertility. Anglo-Saxons celebrated Eostre’s festival in April, marking the renewal of life. Similarly, Easter eggs stem from the fact that in animistic traditions the egg was a powerful symbol of fertility, new life, and creation. Long before their incorporation into Easter, eggs were used in spring rituals to symbolise rebirth and the emergence of new life from the earth; eggs were decorated and exchanged as well as used in various fertility rites.

Islam

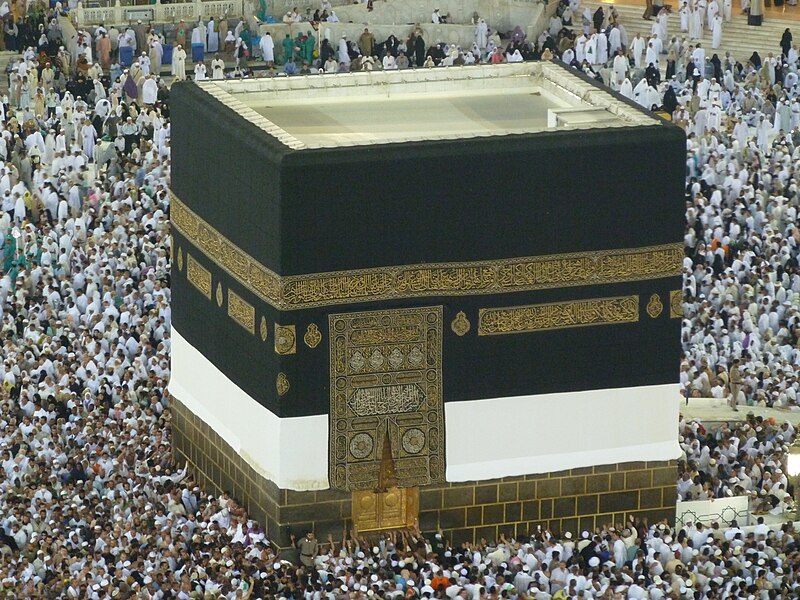

Something similar also occurred in Islam. As is well known, the Black Stone (al-Hajar al-Aswad) enshrined in the Kaaba in Mecca is a sacred object in Islam and traditionally believed to have come from heaven, with some Islamic traditions describing it as a stone sent down by God. While its origins remain a subject of debate, one popular theory is that the Black Stone is a meteorite, which would explain its revered status as something that ‘came from the heavens’. Meteorites were often considered divine or supernatural objects in ancient times due to their mysterious origins and unusual appearance.

Note, too, that the pre-Islamic peoples of the Arabian Peninsula, including various Arab tribes, often worshipped stones, rocks, and other natural objects as part of their animistic religious practices. This form of worship was part of a broader belief system in which natural objects, celestial bodies, and idols were considered to possess spiritual significance or to be the dwelling places of gods. Additionally, the Kaaba itself was a major shrine even prior to the birth of Islam, housing numerous idols and sacred stones, including the Black Stone.

As is typical of animistic religions, pre-Islamic Arabian religions were deeply tied to nature worship, with rocks, trees, wells, and other natural features regarded as sacred. This was part of a broader animistic worldview where deities were believed to inhabit natural objects, and these deities were honoured or appeased through offerings and rituals. Sacred stones were often the focal points of rituals, including sacrifices, prayers, and offerings. Arab tribes made pilgrimages to these stones, seeking blessings, guidance, or protection from the deities believed to reside within them.

Judaism

In Judaism, while there is no universal agreement, historical and archaeological evidence suggests that Yahweh (aka YHWH), the God of the Jewish faith, may have originally been conceived as a storm or weather deity, similar to other ancient Near Eastern gods. In early Hebrew texts, Yahweh is often described in terms associated with storm gods, such as riding on the clouds, controlling lightning, thunder, and rain, and causing earthquakes.

The Psalms and other poetic sections of the Hebrew Bible frequently use imagery of Yahweh as a powerful force of nature. Yahweh’s attributes bear similarities to those of Baal, a prominent storm god in the Canaanite pantheon, who was also depicted as riding clouds and wielding thunderbolts. Over time, as the Israelite religion developed, Yahweh absorbed and redefined these attributes even as they were merged into his identity as the sole, supreme deity.

By the Axial Age, Yahweh had evolved from being a regional or storm deity into the national god of Israel, and later, into the singular, universal God of Judaism, reigning over the entire world. Moreover, this transformation involved an ethical shift from his association with natural phenomena to a broader role encompassing justice, law, and covenantal relationships with the people of Israel. Therefore, while Yahweh’s identity as a storm god was part of his early worship, this aspect became integrated into a more complex and monotheistic understanding as the Israelite religion evolved.

***

In this connection, I note what can only be described as a nearly unbelievable aspect of animism that can be found in all three Abrahamic faiths. That is to say, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all share a belief that their universal and omnipotent God is definitely a gendered deity. For example, we see this expressed in the opening words of the Lord’s Prayer, attributed to Jesus himself: ‘Our Father who art in Heaven…’ (emphasis added). Given it is now well established that the universe is at least 13.8 billion years old, while planet Earth is approximately 4.5 billion years old, and, further, that every form of life on earth is a descendant of a single-celled organism that existed around 4 billion years ago, it can only be described as mind-blowing that the approximately 4.3 billion adherents of the Abrahamic faiths still believe that God has a gender. This implies that God, the omnipotent creator of the universe, has a penis!

Yet, when seen from the viewpoint of animism, this is not the least bit surprising, for without gender, whether male or female, coupled with superhuman abilities, how could a god or gods ‘hear’ the entreaties of believers who constantly and unendingly requested blessings and protection for themselves and those around them? While the attribution of male gender to the Abrahamic deity may stem from patriarchy, the intimacy of believers’ interpersonal relationship with a gendered deity, male or female, stems directly from tens of thousands of years of animistic practice. One could, for example, hardly be expected to pray: ‘Our it who art in heaven…’

By this point, the reader may be thinking: ‘All right, so perhaps all of this is true, but what does it have to do with Buddhism? How does this explain that Buddhism is now a religion, but once was not?’

That question will be addressed in Part Two.

Related reading

Can Religion Save Humanity? Part One, by Brian Victoria

The Highbrow Caveman: Why ‘high’ culture is atavistic, by Charles Foster

Awry in the Orient: some problems with Eastern philosophies, by Nicholas E. Meyer

1 comment

The article implicitly touches on broader philosophical issues, such as the nature of belief and whether religion is an inherent part of human nature or a social construct. The debate over whether belief in a god is essential to religion challenges readers to think about the ways in which spirituality and religion can manifest in diverse forms. For example, Buddhism’s focus on personal development, meditation, and the pursuit of enlightenment might be seen as a non-theistic form of religion, demonstrating that the practices of a religion can exist independently of the concept of a god.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate