Introduction

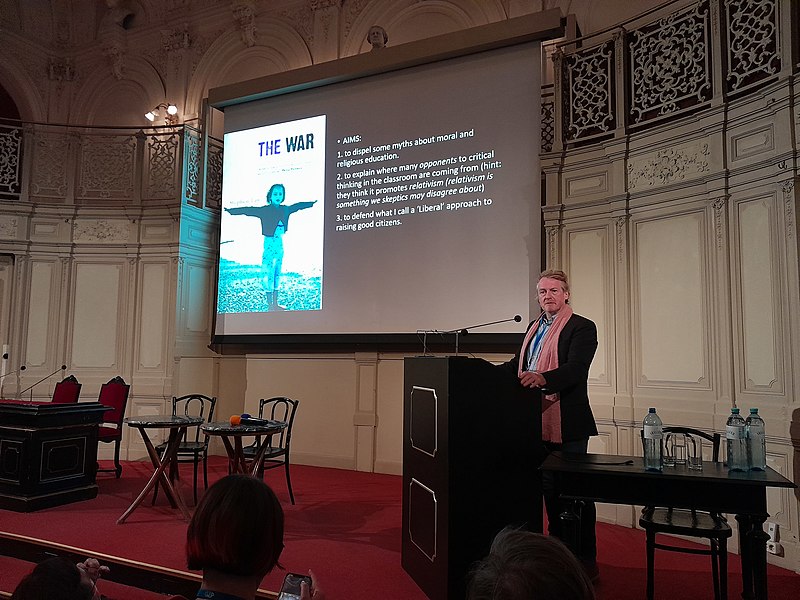

The modern architect of the ‘evil-god challenge’ and a notable advocate of humanism in the 21st century, Dr Stephen Law has contended for unbelief against some of the biggest defenders of religion and the best theism has to offer from his positions in the Oxford University faculty and at Heythrop College, University of London, including William Lane Craig and Alvin Plantinga. His popular writings include The Complete Philosophy Files (2000), The Philosophy Gym (2003), The War For Children’s Minds (2006), Really Big Questions For Daring Thinkers (2009), Believing Bullshit: How Not to Get Sucked into an Intellectual Black Hole (2011), and Humanism: A Very Short Introduction (2011). He is the editor of the philosophical journal Think.

Below is the transcript of my interview with Law, lightly edited for clarity and concision.

Interview

Samuel McKee: How did you get into philosophy?

Stephen Law: I got kicked out of school in my teens so had two goes at my A-levels. I found it very boring and became a manual labourer building the M11 before becoming a postman for a while. I did a lot of reading, and one book led to another. Eventually, I was only reading philosophy books and then I realised that that was what I was really interested in. I applied to university as a mature student and bullshitted my way in without A-levels. By some miracle, I talked my way in, and I just never left.

How long have you been in academic philosophy now?

I went to university at about 24. That was at City University London, the only one that would accept me. I got a first and then I did the BPhil at Oxford before doing my doctorate there. I was a Junior Research Fellow there for three years at Queen’s College, Oxford, doing apprenticeships. Then I ended up with a job at Heythrop College, University of London. So, I’ve been in academic philosophy since 1987!

In your time you have gone up against a lot of the most well-known religious philosophers like William Lane Craig and Alvin Plantinga. Can you say something about those experiences and what it has been like being on the academic front of defending humanism and atheism in the last 20 years?

When I first started, I wasn’t particularly interested in philosophy of religion, but then I ended up at Heythrop, which is a Jesuit college. I have always been puzzled by how people think and why they believe weird stuff, especially when they think very differently from me, and how they ended up there. For that reason, religion became interesting to me. Then I published the ‘evil-god’ paper in 2010 which became quite notorious, and I was invited to debate a lot on that. I enjoyed doing those debates. William Lane Craig—I quite enjoyed that one.

Could you explain the ‘evil-god challenge’ for us?

Other people had (annoyingly) already come up with it. I thought I had invented it but then realised that others had had that thought before. So I didn’t originate it but I did shape it and defend it in a certain way.

The simple way of explaining it is that if you were to suggest to most people that the universe is the creation of a powerful but malevolent deity, they wouldn’t accept it. If you ask them why, they will point out the window and point at ice cream, rainbows, and children laughing and say that there is way too much good for this to be the creation of a supremely malevolent creator; if it was so, the world should look like a hellscape. If that is a reasonable response—and I suspect that it is—then we can quite reasonably rule out an evil god on the basis of observed goods. The question is then, ‘Why can’t we reasonably rule out a good god on the basis of observed evils?’ Why is one of these things something we can do but not the other? What is the difference?

In an increasingly irreligious Britain, why is humanism a good alternative for people who are looking to replace religion? Do you think the average non-believer should engage more with organised humanism?

Only if they are interested! I don’t think there is any obligation to do that.

What does it offer?

When people say they are humanists it is often because they have political concerns about the relationship between religion and the state or the way in which religion can insert itself into people’s lives and perhaps have an unhealthy effect. Humanists are quite concerned about that. They are particularly concerned about schooling and raising good citizens, encouraging young people to think for themselves. Humanism is attractive to quite a few people because these things do concern them, and I suspect that is the main reason many people are drawn to it.

There is other stuff too. It provides an opportunity to talk to like-minded individuals. A lot of people are humanists and don’t realise it. Just because you are an atheist doesn’t mean you are a humanist. Stalin was an atheist but he wasn’t any kind of humanist! Humanism is like ‘atheism plus’, as Julian Baggini puts it. So, humanism is atheism plus a commitment to living a good life, an emphasis on applying reason as best as we can, and a commitment to political secularism to ensure that the state remains neutral when it comes to religion. We can lead meaningful lives in the absence of religion.

Humanists are often involved in providing humanist alternatives to religious ceremonies, which is a really big and growing part of organised humanism. Humanist marriages and humanist funerals now outnumber religious ones. People want to mark big occasions even if they are not religious and they shouldn’t have to [feel obliged to] bring religion into it.

You are now involved with the Oxford University Department for Continuing Education where you teach students of all ages. Why is it valuable for all people to study philosophy and to learn to think philosophically?

Number one, it is fun! I have always loved thinking about philosophical stuff. How do we know we aren’t living in the matrix? Is there a god? What makes things right or wrong? How do I know that my parents aren’t robots? A lot of people and a lot of kids are drawn to these questions. A lot of adults continue to think about them. It’s a lot of fun to think about it.

Also, I think it is good for you to question things. I think everyone should take a step back every now and then and just ask themselves the key searching questions about why they believe what they do. We go about justifying things. Don’t just go with the flow or be a moral sheep but actually just stop and think. That is how moral progress is made.

It turns out that if you run philosophy programmes in schools there is less bullying. Philosophy in schools is great for kids culturally; it boosts their intelligence measurably. So why wouldn’t you be doing that? And if you raise people to think in these kinds of ways, they are less prone to indoctrination and being manipulated and they have more immunity to internet bullshit. And there is also evidence to suggest that those are the kinds of people who do the right kind of thing when push comes to shove and things get really bad.

What are you working on at the moment?

Mostly walking the dog, playing the drums, and going climbing occasionally. Other than teaching, I am thinking about what to do next in philosophy.

Related reading

Can science threaten religious belief? by Stephen Law

Atheism, secularism, humanism, by A.C. Grayling

The future of biology, science vs. religion, and ‘ideological pollution’ in science: Interview with Jerry Coyne, by Samuel McKee

‘Religion is a killer now’: interview with Professor Peter Atkins, by Samuel McKee

Bringing back the dialectic: interview with Stephen ‘Rationality Rules’ Woodford, by Samuel McKee

The new faces of unbelief for Generation Z: the rise of the British social media atheists, by Samuel McKee

The philosopher’s curse(s), by Nicholas E. Meyer

Two cut-the-nonsense thinkers who overcame the philosopher’s curse(s), by Nicholas E. Meyer

Consciousness, free will and meaning in a Darwinian universe: interview with Daniel C. Dennett, by Daniel James Sharp

‘The Greek mind was something special’: interview with Charles Freeman, by Daniel James Sharp

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate