Today marks the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, and below is reproduced an excerpt from Jim Herrick’s 1982 history of the Freethinker covering how the magazine fared during that terrible but necessary conflict. Some of the themes explored by Herrick remain all too relevant to this day. And, as an aside, Chapman Cohen’s end-of-war reflections on the looming Cold War age are reminiscent of Orwell, I think.

The excerpt appears as it does in the book, with just a few editorial insertions in square brackets (only ‘[the Germans]’ comes from Herrick). The dates Herrick gives in brackets after quotes and references refer to the relevant issue of the Freethinker. You can find these issues, and almost all of the Freethinker‘s back catalogue, in our historical archive here. You can also find out more about Jim Herrick in Bob Forder’s obituary of him here.

~ Daniel James Sharp, editor.

“The Armistice of 1918-39 is at an end. Since 11 o’clock on September 3 this country has been at war with Germany, and if ever war was justifiable it is the one in which this country is now engaged.” (10 September, 1939.) Although the Freethinker had always abhorred militarism, it was almost with a sense of relief that Cohen [Chapman Cohen, editor of the Freethinker, 1915-1951] wrote of the declaration of war against Hitler. He had earlier written that the choice was not between peace and war but between war and something worse: “The present conflict, which may or may not end in war, is not a conflict between two nations or between two groups of nations. It is a fight for the maintenance of even the moderately decent level of life that has been achieved.” (30 April, 1939.)

Cohen did not share illusions, soon to be nurtured by British propaganda, that the allies possessed a moral superiority or that the war was caused solely by the evil genius of one dictator. In writing of a justifiable war a few months before the declaration of hostilities, Cohen explained that “I do not mean by this that the hands of this country are spotless”; “on the contrary, there are some very nasty spots on our hands, and these spots will not be easily erased. After all, it was Britain that in modern times set the standard of national greatness as consisting mainly in vast ‘possessions’ in all parts of the globe, and so ultimately made it necessary for other powers to break the peace of Europe if they were to become ‘great’ powers also.” (30 April, 1939.)

Opposing “the theory that war is the product of one man’s activity”, Cohen wrote:

Such men as Hitler are the scum that society may throw to the surface, and it should be treated as a cook treats scum in the cooking — it should be thrown on one side as soon as noticed. In life events explained men, and the origin of the criminal gang against which we are now fighting is in the world they found established. (17 September, 1939.)

Attitudes to War

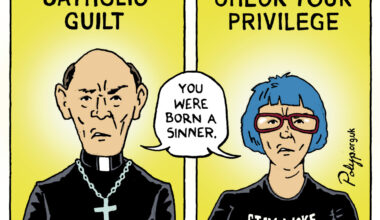

Some of Foote’s [G.W. Foote, founder and first editor of the Freethinker, 1881-1915] articles from the First World War were reprinted as relevant comment on the repetition of man’s inhumanity to man. And some of the same themes were to be repeated in the Freethinker: the uselessness of days of prayer and the impossibility of believing in a benevolent god during wartime, the rights of atheists to affirm and to opt out of church parade, the position of conscientious objectors, the need to avoid as much censorship as possible despite the demands of propaganda, the inanity of assuming all Germans were cruel monsters.

Innumerable comments were written about national days of prayer. They were compared to magical dances performed by medicine men when tribes go to war. What could be the use of prayer? “Was it intended to call God’s attention to the fact that there is a war on, and give him a polite reminder that we expect him to do something?” (15 October, 1939.) An Acid Drop [a once-common feature in the Freethinker, these were bitingly critical sallies against the religious nonsense of the day] parodied Churchill in printing “What the Archbishop of Canterbury did not say on the National Day of Prayer. — Never has so little been done by One, for so few.” (30 March, 1939.) Lord Halifax, Foreign Secretary, asked the public to form prayer groups and to spend a portion of each day in prayer: “Bearing in mind the opinions of large numbers of men in the British forces, a more disgraceful exhibition of using a public position to conduct a Christian propaganda has seldom been heard.” (28 July, 1940.)

There was indignation at the difficulties encountered by atheists who wished to affirm rather than swear an oath of loyalty when they joined the forces. Freethinker [sic] readers were regularly informed of their rights and asked to report examples of discrimination. Two examples are typical. An individual wrote a letter recounting his experience of being sworn in for service in the RAF:

On the form I had to fill in, opposite the words “Religious Denomination” I had written that I was an Atheist, although the recruiting officer had advised me to write “Church of England”. When the attestation officer saw this he endeavoured to get me to change it to one of the recognized religions, and said that I must have a religion. When I asked him why I should have a religion he did not answer, and I am afraid to say that he was not at all sure how an Atheist had to be sworn in. I told him that he would have to change the words “Almighty God” in the oath, and that I could attest by affirmation, by my own integrity. He replied by saying that an Atheist couldn’t have any integrity. Perhaps you can guess my reaction to this piece of unprecedented “cheek”. I told him that an Atheist had more integrity than a Christian could ever have, because an Atheist used common sense in being what he was. Furthermore, I let him know that an Atheist had the integrity to be not afraid to stick to his principles in the face of all intimidation and opposition, and that whatever trouble I had to put up with in the R.A.F. I would continue to stick by them, and not insult them by telling lies for the sake of a lot of red tape and hypocrisy. (29 October, 1939.)

Another reader sent in a succinct recollection of what had happened when he had enlisted in the previous World War:

The officer is taking down particulars at the Recruiting Office:—

Officer: “Religion?”

I: “None.”

(The officer writes “Church of England”.)

I: “I say ‘No religion’ and you write ‘Church of England’.”

Officer: “Same thing.” Then, after a pause: “Young man, if you want to kill someone, you must have a religion.” (18 October, 1942.)

Protest also came as a result of the unpleasant fatigue duties, such as cleaning the lavatories, which were given to those who opted out of the Army Church Parade. The provision of Bibles for service men and women, with a message from the King urging Bible reading, was seen as insulting to a force that contained Mohammedans, Buddhists and unbelievers:

All are asked to believe that the book which kept religious persecution alive, which taught the belief in witchcraft, which sanctioned slavery, which taught exorcism as a method of curing disease, which told women they were to obey their husbands with the same unquestioning obedience that they obeyed Jesus Christ, the book which substantially ignores the family, which has nothing to say concerning art, science, education, philosophy, and which out-Nazied Nazi brutality with its doctrine of eternal damnation, it is this book that has been “a wholesome and strengthening influence in our national life”. (15 October, 1939.)

The Freethinker strongly objected to the view that the war was “being fought for the preservation of Christianity” (25 August, 1940.) and to attempts by the churches to capitalise on the grim situation. “The Government at the opening of the war avowed its determination to prevent profiteering. But it probably did not interfere with the greatest of all forms of profiteering, that of the Christian Church… we may say that the exploitation of human fear and ignorance in the interests of superstition begins with the earliest and persists with the latest forms of religion.” (8 September, 1940.)

Strong distaste for warmongering and any Christian relish for war was registered:

Mr. Winston Churchill said: “We will make them [the Germans] bleed and burn.” As the Daring Old Man on the Flying Trapeze of the war, jumping from Turkey to Casablanca, Winston has said something of which millions of Christians have heartily approved. It is a thoroughly Christian sentiment in line with Christian history and Christian traditions — far more so than when Winston said, “War is an evil thing.” (28 March, 1943.)

Duff Cooper suggested that “there is some profound quality that differentiates the Germans from other people”. Cohen dealt with such a view with the same anti-mystical, sociological approach that he brought to religion. He quoted J.S. Mill: “Of all the vulgar modes of escaping from the consideration of the effect of social and moral influence on the human mind, the most vulgar is that of attributing the diversities of conduct and character to inherent natural differences.” Cohen continued:

From my youth upwards it has been plain to me that while there may be different endowments with individuals, so that some Germans may be as independent in their outlook as some Englishmen, and some Englishmen as sheep-like in their mentality as some Germans, it is the social and cultural environment in which we find ourselves that is responsible for the forms of expression of those qualities that are common to all. (29 October, 1939.)

Comment in the Freethinker in the thirties had compared fascism and Nazism to the phenomenon of religions. A report of the plan of Rosenberg, the “German ‘racial’ expert with a Jewish name”, to replace the Bible by Mein Kampf highlighted a religious component of Nazism:

Mein Kampf is to take the place of the Bible in German Churches. The State Church is to be anti-Atheistic and one in which all German men and women, youths and girls “acknowledge God and his eternal works.” The matter is interesting because, first it disproves the religious talk of Hitler and his gang being all Atheists — they are, as a matter of fact, mainly religious. Next it shows that in the attempt to enslave Germans perpetually the gang can find no better implement than religion, and thirdly, in establishing a National Church where only one form of religious belief is permitted, Hitler and his gang are pilfering the ideal of the Roman Church, and, indeed, of every established Church in Christendom. The brutalities of Hitlerism should not blind intelligent people to these pregnant facts. (14 December, 1941.)

Hitler was as fickle and opportunist in his attitude to churches as to any other group. He was originally Catholic, but although some parts of the Catholic Church had shown sympathy for fascist elements, it would be as wrong to brand Hitler as a puppet of any church, as to assign his evils to any atheism. Cohen was asked to justify his rather ambivalent statement that Hitler was a “deeply religious man” and he quoted an early utterance of Hitler’s from the “sixpenny Hammer and Anvil”: “I believe it was God’s will to send out a boy from here into the Reich to make him great, to raise him to be Fuehrer of the nation, to enable him to lead his homeland back to the Reich. There is a higher dispensation and we are nothing but its instruments…” (13 August, 1939.)

A complete and judicious assessment of the relationship between Nazism, Hitler and religion would need more space than is available here, but it would have to include reference to some Christians’ courageous resistance to Nazism as well as Pius XII’s failure actively to condemn Nazism.

If churches could debase the epithet “atheist” by attaching it to Nazi rulers, they were presented with problems when atheistic Russia became an ally. The picture established in the twenties and thirties had to be reversed: “The picture of Russia as a land swarming with Atheistic criminals is dropped, and we get the information that the attempt to convert people to Atheism has been a miserable failure.” (20 April, 1941.)

The Prime Minister and [Anthony] Eden emphasised that they were still opposed to communism. Cohen saw this as “a soothing measure against certain powerful home interests, religious and other, to whom a boycott of Russia would be welcome”:

We have no great liking for Communism, but it must be met as a theory of social life and argued for and against as we discuss other social theories. Loose talk about robbery and murder, backed by lying religious opposition, will not make for the lasting peace of the world. Even Mr. Churchill may need reminding that great as are his services to the country during this war, his reputation as an authority on social and economic evolution has yet to be established; but, as we have said, we fancy that the Prime Minister’s declaration was not intended for Russia at all, but for a class in this country to whom both Mussolini and Hitler owe much for the positions they now occupy. (13 July, 1941.)

An absurd feature of the establishment’s dilemma over the alliance with Russia was seen in the refusal to permit the Russian national anthem to be played with that of other allies on Sunday evenings: “That is not too good an omen for the new world that is to follow the war. A desirable peace with Russia left out can be desirable only to fools — and worse. It means another armed peace which is just a degree better than actual war. But it ends in war, as experience proves.” (20 July, 1941.)

The Freethinker did not neglect to point out that freethinkers were among the victims of Nazi persecution. Charles Bradlaugh Bonner, while appealing for funds to help freethought refugees, referred to the arrest of Captain Voska, President of the Czech Freethought Society, as soon as Hitler marched into Prague. (2 July, 1939.)

Free Speech in Wartime

Freedom of thought is hard to preserve in times of war, but the Freethinker stood firmly for maintaining all possible freedom of speech. In the months before war the Government promised to form a Ministry of Information if war came. Cohen immediately gave a warning: “I regard with the greatest dislike a Government propaganda that can control the news, that can suppress the truth and circulate lies whenever the Government of the day considers either of these courses advisable. If we are in earnest in fighting Fascism and other forms of tyranny, we should fight them wherever they are met.” (25 June, 1939.)

Cohen feared the long-term consequences of what he called “the ministry of misinformation” and was pessimistic about the political parties’ defence of independence of thought:

Much of this we must submit to for “the duration”, but we should do so with a full sense that they are restrictions, and with the resolve to end them with the war. In this last task we must not look for getting much help from the political parties. For a long time, whether we are dealing with Labour or Conservative, the tendency has been in and out of Parliament in the direction of regimentation. The party issues orders, the members of the party obey… (1 October, 1939.)

Petty British censorship was condemned. The Government at the beginning of the war decided to close cinemas, theatres and places of entertainment on Sundays. Cohen wrote: “Our soldiers showed that in the last war laughter was often escape from insanity… Bernard Shaw and Oswald Stoll have protested against the Churches being opened while the theatres are closed. Presumably the Government thinks that people do not go to Church for entertainment — unless they are Freethinkers — and that there would be no overcrowding, in any case.” (17 September, 1939.) The ban on Sunday entertainment was soon modified and defenders of the Sabbath later became disturbed at the encroachment of entertainment into the Lord’s Day.

The B.B.C. was, as ever, a target of the Freethinker’s wrath. Professor Joad’s performance in the Brains Trust was especially reviled. Joad’s metaphysical meanderings were seen as a betrayal by a one-time rationalist.

Since Dr. Julian Huxley left England for the United States our irrepressible friend and philosopher, Professor C.E.M. Joad seems to have been getting quite a lot of his own way in connection with the Brains (!) Trust of the BBC.

Without the personal sobering influence of Huxley’s materialistic antidotes, the metaphysical toxin of Joad appears to be developing quickly of late. (22 February, 1942.)

(Huxley’s refusal to call himself an atheist and enthusiasm for a non-deistic religious spirit did not always endear him to freethinkers either.)

Joad’s statement at a Ministry of Information meeting that one of the troubles of to-day “was that a generation had been brought up without creed or code, and religious leaders must restore spiritual values” was sharply criticised. (22 February, 1942.) After the war a particularly strong lambasting of Joad by a Mr. Wood, coupled with a complaint about his failure to answer letters, produced a letter from Joad which began: “There now, Mr. Wood, you have drawn me!” After dealing with anti-theistic arguments and the idea that matter is not immortal Joad concluded with two questions:

(i) Why do you always assume that when a man changes his views he does so from interested motives, or why, if you don’t assume it, do you, nevertheless, contrive to imply it? (ii) Or is it only with regard to a change from views which you do hold to views which you don’t, that you make this assumption and suggest this implication? Does it never occur to you that a man might honestly disagree with you? (4 April, 1948.)

Dorothy L. Sayers, whose radio plays about the life of Christ were very controversial because they dramatised New Testament characters using everyday language, was provoked into a very tetchy letter by Cohen’s criticism of the way he saw her being used by the B.B.C. as a popular writer turned Christian apologist.

Control of information and discussion did not leave much need for use of Blasphemy Law, not yet abolished. However, “perhaps the most ridiculous blasphemy case that has ever taken place in the British Isles” was reported in 1940. A hotel proprietor in Jersey had been photographed, while lying arms outstretched and feet crossed, suntanning on the beach. A visitor gave him a copy of the photograph having used red ink to draw in nails and drops of blood in imitation of the crucifixion. The hotel proprietor put the photograph in his pocket and thought no more of it until he took it out by mistake when asked for his passport at the Aliens Office. A shocked official gave the picture to the Attorney General of the island. Proceedings went ahead and he was sentenced to one month’s imprisonment. The Home Secretary refused a pardon, but cancelled what remained of the sentence as an act of clemency. The hotel proprietor’s more enduring punishment was to lose his licence as a hotel keeper after being found guilty of a criminal offence.

Bombing of the Freethinker Offices

The graver events of the war threatened the Freethinker’s continuity. Paper shortage was a continual problem and the number of pages was reduced in 1942. Bombing of cities became a serious threat in 1941. Christians, stretching apology for God’s behaviour to its uttermost, suggested that London was being bombed because God wanted to give “a chance to rebuild London”. The Freethinker poked fun at such an idea:

When God gets to work he is too promiscuous. Someone gets hurt, but he never appears to discriminate between his friends and his enemies, although often enough, those who turn out to be his best friends are treated as his worst enemies. For all the improvements that have taken place in the character of God are due to those who were counted as opposed to him. (6 July, 1941.)

The Freethinker did not escape and on the evening of 10 May, 1941, its offices were burned to the ground. (The N.S.S. [National Secular Society] offices were included.) “Nothing was left but a mass of rubbish that was still smoking on May 14.” The loss was severe: premises, paper, stock of books and pamphlets, and a linotype machine and other printing equipment. The most irreparable loss was between 1,000 and 1,500 volumes “representing a fine collection of (mostly) scarce books on Freethought subjects dating back to the middle eighteenth century, and some earlier of a semi-religious character.”

Cohen had foreseen the danger and an emergency issue which he had kept set up ready came out on 18 May. So the continuous run of the Freethinker was not broken. Nor was Chapman Cohen’s indefatigable spirit daunted:

It is not well to dream plans, although we all do it. I am nearing my seventy-third birthday anniversary, and have sometimes dreamed of being able to throw on one side all the responsibilities of my position, including that of editor of the “One and Only”, a post which I prize more than I should that of our Prime Minister. Not, of course, to cease writing for the paper. That is not so much work as a safety valve. But just to watch the movement in which I have spent my life growing stronger and stronger, but never so strong that it could in a state of pampered supremacy forget its history and significance and wield a slave-ship in the name of freedom.

And now. Well I have, in a way, to begin all over again. To build almost from the ground upward. But German bombs can no more crush Freethought than British tyranny was able to crush or silence that band of heroic men and women who did so much to build up a heritage and to establish a tradition.

The Freethinker goes on and with it the advanced movement. (25 May, 1941.)

As the end of the war approached, there was talk of giving thanks to the Almighty and returning to Christian values. The Bishop of Southwark said that after the war “the people must be led back to ‘sanity and right values’” and that in Europe the “need for Christian literature will be enormous.” The Freethinker was sceptical: “We have our doubts. There was no shortage of religious literature in pre-Hitler times, nor was there in any other part of Europe.” (8 April, 1945.) The Annual Report of the National Secular Society’s Executive summed up the war years:

The past six years have been a period of strain and trial, of danger and disruption such as this country has never before experienced, and in the case of a loosely knitted propagandist movement such as ours it might well have ended in complete disruption. The situation reminds one of a story that goes back to the stormy days of the French Revolution. A man, noted for his boasting, was asked what he did in the Revolution. He replied “I lived”, and in sober truth that was something of an achievement. Looking back at these six years we might say with pride that we continued during one of the most trying periods of our history. Many of those who carried on the work were whisked away to some other area or joined fighting forces. Halls ceased to be available for public meetings, and travelling was reduced to a minimum. The dark streets acted as a curfew and kept people at home. These six years covered a period that we may now look back on with interest, but which we lived through with considerable discomfort. (3 June, 1945.)

Some hope was seen in an increase of membership, and a growth of financial resources, and the demand for the Freethinker combined with the paper shortage meant that for the only period in its history subscriptions to the Freethinker had to be refused. The Freethinker continued to circulate around the world. A consignment of freethinking books and pamphlets bound for the Truthseeker were seized by American custom officials: “The officials had the impudence to say that because they were anti-religious publications and in any case were not in line with the war effort, they could not be permitted to pass.” (3 June, 1945.) The literature was released after legal action was taken and judgment was given in favour of the Truthseeker.

The 1944 Education Act

The same Annual Report drew attention to a major Parliamentary Act, which freethinkers saw as a step backwards: “Under cover of concern for a better education our war-time government succeeded in passing a Bill which restored to the Churches a great deal of the power they lost by the Education Act of 1870.” (3 June, 1945.)

Freethinkers thought that the churches were taking advantage of the war to increase their influence in schools. A headline “Kidnapping” expressed this feeling and the piece stated: “If we win the war only to hand over the control of schools to the clergy we shall have paid a heavy price for victory.” (8 May, 1942.) In 1941 the Archbishop of Canterbury and others had launched Five Points, which included compulsory R.I. [Religious Instruction] in schools (with the right of withdrawal), R.I. as a subject for teachers’ certificate, and a daily act of worship in schools. The Secular Education League campaigned against an approach which would give greater statutory importance to religion in schools than hitherto. A leaflet was printed, signed by Professor J.B.S. Haldane, Julian Huxley, Mr. Laurence Houseman, Dr. Joseph Needham and others. It warned:

The present international crisis, the suspension of political party controversy, and the almost complete pre-occupation of the mind of the people with the life-and-death struggle of the war have provided the opportunity long awaited by the advocates of compulsory State-aided religious education to make anew effort to secure their ends. What they could not achieve by an appeal to justice and equity they seek now to obtain through panic in a time of national emergency. (15 March, 1942.)

The extent to which the 1944 Education Act was deplored as retrogressive can be seen in a front-page article “The Education Crisis” (19 March, 1944.) A comparison was made with the vigorous campaign of Freethinkers and Nonconformist Christians so that “the State would not interpose in matters of religion” at the time of the 1870 Education Bill. “The slogan was then ‘Education, Free, Compulsory and Secular’. In this ‘Joe’ Chamberlain was one of the leaders. In the end a compromise was agreed upon by the Churches. The Nonconformists sold the pass, and religion has been one of the strongest obstacles to a sound system of national education ever since.”

In contrast, “To-day we have another clash over religious education, and this time there is an attempt by a Tory Government, which has long since outlived its legitimate span, using a majority that dare not face the electorate with the religious clauses of the Bill now before the House of Commons.”

Talk about “religious equality” by the Minister of Education was described as “humbug, for when our Prime Minister and the Minister of Education talk about religious equality they mean at most equality among the Christians.” There was no hope that

Atheists would be permitted to enter the State schools in order to teach pupils what science has to say concerning the origin of gods — all the gods. The utmost favour bestowed upon these would be the withdrawal of children from religious instruction which the parents disliked. But the saturation of the whole of the school time is aimed at; and it takes a politician to appreciate the favour of not being compelled to eat a dinner one doesn’t like, but to be still forced to pay for one that he will not eat. Christian freedom is a very curious thing whenever and wherever it is encountered. (19 March, 1944.)

Another front-page on education expressed opposition to R.I. on the basic grounds that it was not true education, with knowledge being imparted and a sense of inquiry encouraged:

The “great lying creed” as Heine called it, is dying. That is why the clergy feel that by some method the children must be captured. With all other subjects the teacher can afford to wait until his pupil is able to appreciate the quality of what is being told him; with religion, belief must precede conviction. The pupils of the parsonage cannot wait until development is expressed in understanding. (14 May, 1944.)

The Butler Education Act was passed and justified freethinkers’ fears that it would give religion a firm footing in schools in subsequent decades. In contrast to the continued strength of worship and religious education in schools there has been a general gain in scepticism which has come from wider education in the post-war years.

The End of War

The end of war saw the Freethinker commenting upon the forthcoming celebrations, deploring the bloodshed and lamenting the trumpeted thanksgivings:

We are writing these notes while everyone is anxiously awaiting the news that Germany has surrendered. Every arrangement has been made to “celebrate”: the public-houses are to have a larger quantity of beer and the Prime Minister has asked all the churches to open their doors and return thanks to God for our “victory”. We fancy that this piece of advice is given with an eye on the coming General Election rather than an expression of Mr. Churchill’s profound religious feeling. But votes are votes, and to get the religious vote on the side of A or B or C is very important for political success. After all, votes are votes, and two of them will overcome one without the slightest regard to their ethical or social value. Certain it is, from the wider point of view, that religion has been one of the casualties of the war. No war has started with a greater outburst of “the trumpets of the Lord”, and never was the futility of the trumpeting made more obvious. To the common man it would seem that God should have done his best to prevent the war, or if the war escaped his notice, some very plain exhibition of his interference — on our side, of course — should have occurred. A deity who stands looking on while the terrible brutality of the German Nazis manifested itself seems to fall short of what sense and decency would expect. Still, the combination of more beer and an outbreak of thanks to God for giving us victory may go well together. There are many forms of intoxication, and a combination of all forms is a very powerful thing. Still, there seems to be something wrong in a deity who stands, or sits, idly by watching the terrors of the German prisons and then receiving thanks from his children for ending the war after five years of bloodshed, brutality and disaster. Returning thanks to God in the present situation merely emphasises that both camels and Christians take their burdens kneeling. (13 May, 1945.)

Further bloodshed and brutality were to cap the horrors of the war in Europe and point to a major factor in the second half of the twentieth century: the dropping of atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Cohen foresaw a new scale of horror for war and urged the need for international control:

The sanction given to the use of atomic bombs has stripped war of all its “glories”, and marks miscellaneous killing as perfectly proper. The world war has shown armed conflict at its greatest and at its worst. But you cannot marry the higher social qualities by wiping out old and young, good and bad, with complete immunity. To-day, we now call the dropping of atomic bombs war; we are afraid history will give it an uglier name.

…I think there is one way out, and only one. I have been pressing for it for about fifty years without much apparent success. I suggest that each of the “civilised” countries — the uncivilised are not really dangerous — should agree to complete national disarmament and leave the settlement of any disputes that may arise to an international court, which alone should wield sufficient material forces to enforce their decisions. But the courts must have adequate power to enforce their verdicts. The courts now existing have no such power. If one of the disputants refuses to obey the court the case drops. So long as the methods that now obtain are in force, chaos and war will continue, and so long shall we be threatened with wars, or what is almost as bad, perpetual preparation for war. (19 August, 1945.)

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate