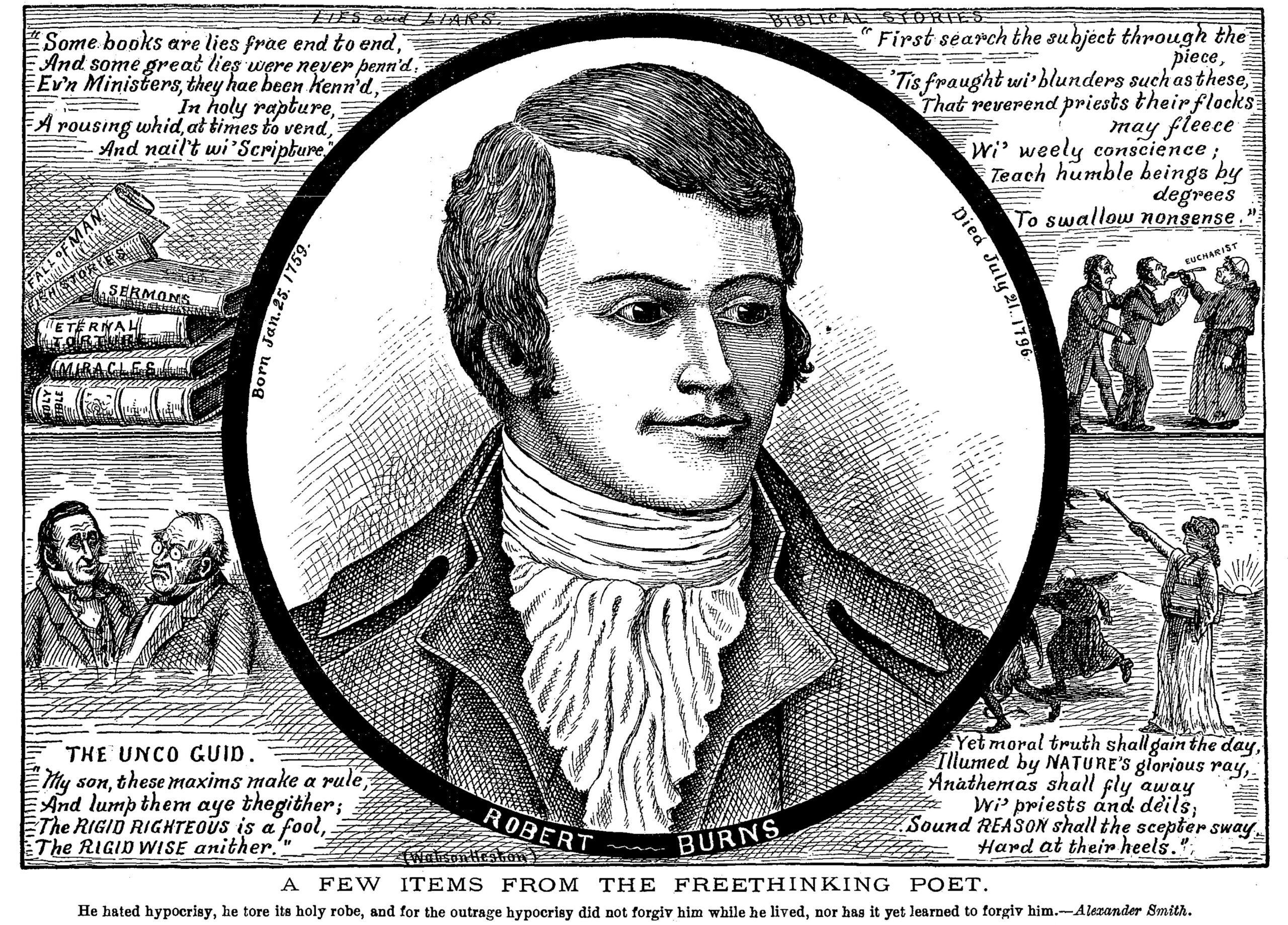

In honour of Burns Night on 25 January, on which Scotland’s greatest and most beloved poet is celebrated with whisky and haggis throughout the land, here is a cartoon by Watson Heston, originally published in The Truth Seeker for Burns Night 1890. It is republished here with permission of The Truth Seeker‘s current editor, Rod Bradford, who recently reminded me of the admiration for Burns evinced by freethinkers and radicals down the years. From Rod’s 2006 biography of The Truth Seeker’s founder D.M. Bennett:

In the early 1870s Robert Ingersoll had a successful law practice in Peoria, Illinois, but devoted much of his time to his lecture tours. He received as much as $7,000 for his lectures on Shakespeare, Burns, Voltaire, and Thomas Paine. “Shakespeare is my bible, Burns my hymn-book,” he was fond of saying.

In Scotland Bennett traveled to Glasgow and Edinburgh, and visited numerous points of interest including Inverness, the capital of the Highlands. He found the homes of John Knox and David Hume as well as the beloved Robert Burns house in Edinburgh. Like Robert Ingersoll, he held the poet Robert Burns in high esteem: “He was not much of a friend to royalty, nobility, and the priesthood,” he noted. “When I meet his statue, as I have done both here and in Glasgow, my hat raises spontaneously.” Before leaving Glasgow for Ireland, he traveled to Ayr to see Burns’s birthplace cottage, monument, and the Bonny Doon River. He realized that Burns was “one of the most natural, simple, and one of the sweetest poets that ever sang, who, though he had some faults and weaknesses, was at heart a true man—really one of nature’s noblemen, one of the highest works of her hand.” At the storied Tam O’Shanter Inn, Bennett confessed to having a small glass of sherry for “Auld Lang Syne.”

It seems to me that, fun though it is, the slightly kitsch nonsense of Burns Night obscures the reality of this complex and profound poet. Much easier to tart oneself up in tartan and declaim to a steaming haggis than to reckon with Burns as a political and religious radical (not to mention the wrinkle that he nearly took a job on a slave plantation; but that’s another story). As an extra, then, please enjoy Don Cameron’s short essay on Burns as freethinker, provided especially to accompany this image of the week.

Was Robert Burns a freethinker? By Don Cameron

To publicly ‘come out’ as an atheist in the second half of the eighteenth century in Scotland would have been a dangerous thing to do. The last execution in Great Britain for blasphemy, of a 20-year-old student named Thomas Aikenhead, had occurred in Edinburgh in 1697. Imprisonment for blasphemy would have been possible or, at the very least, total social disgrace.

Yet at times, Robert Burns came close to crossing the line. He was no lover of the Kirk, which had disciplined him for some of his romantic misdemeanours. He certainly looked down on the Calvinist idea of predestination; the idea that a minority are lucky enough to be the ‘elect’ while everyone else is bound for Hell with no account taken of their virtues or lack thereof.

One of his best poems is ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’, a satirical attack on one of the self-righteous worthies of his local Kirk. In its first verse, he mocks the idea of the elect:

O thou that in the Heavens does dwell!

Wha, as it pleases best thysel,

Sends ane to Heaven and ten to Hell

A’ for Thy glory

And no for ony gude or ill

They’ve done before Thee.

For obvious reasons, this poem was first published anonymously (in 1789).

Burns later, at the request of a friend, removed four lines from an early version of his epic poem ‘Tam o’ Shanter’ (1791). They were part of the description of what the witches had laid out on their ‘haly [holy] table’:

Three lawyers’ tongues, turn’d inside out,

Wi’ lies seam’d like a beggar’s clout;

Three priests’ hearts, rotten black as muck,

Lay stinking, vile, in every neuk.

It seems that his opinions of priests and lawyers were equally disapproving!

And yet, at other times, Burns is respectful of religion. For example, in another well-loved long poem, ‘The Cottar’s Saturday Night’ (1786), he portrays the father’s humble reading of the family Bible in a charming fashion and contrasts this with the pretentious displays of piety by others who claimed to be righteous.

We must remember that Burns lived before geology discovered that the Earth was much older than the Bible claims; before Darwin; before neuroscience; before the critical study of scripture and the history of religions. He had to form his beliefs based on the limited evidence of his time. He was not an atheist, but he was no fan of religious authority.

If he had lived in our times, I think he might have gone further. Burns was also radical in politics. See, for example, his admiration for Thomas Paine and the American and French revolutions; indeed, his 1794 ‘Ode for General Washington’s Birthday’ was unpublished during his lifetime due to its sympathy for republicanism. For his criticism of religious hypocrisy and his political radicalism, then, Robert Burns truly deserves to be called a freethinker.

Read more of Don Cameron’s writing for the Freethinker here.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate