Life in Iran is not lived, it is performed. Every movement, every word, every breath is dictated by an invisible force, an unyielding presence that presses against the people like a rope pulling them back, keeping them in place. This existence mirrors Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano’s endurance art piece, where they were tied together by an 8-foot rope for an entire year. Bound yet apart, close yet untouchable, their every action defined by a force they could not escape.

In Iran, this rope is not a symbol, it is reality. It stretches over homes, cities, and lives, tightening and loosening but never breaking. It wraps around every individual, binding them to rules that dictate what they can say, where they can go, how they must behave. The government’s script is clear: you may speak, but only the approved words; you may move, but only within designated spaces. There is no room for improvisation in this performance of existence. The repetition of this act, day after day, dulls the senses, turning survival into routine. The weight of fear is ever-present, pressing against the ribs like a hand that never lets go.

Yet, within this forced togetherness, there is profound loneliness. Public spaces are filled with bodies, yet each person moves in solitude, careful not to speak too freely, not to trust too quickly. The regime thrives on isolation, feeding suspicion, ensuring that no bond can be strong enough to challenge its power. A glance held too long, a sentence left unfinished: these small hesitations reveal the ever-present knowledge that one misstep can unravel everything.

Survival, then, becomes an art. To live under repression is to master the delicate balance between compliance and quiet defiance. It is the way a woman adjusts her headscarf just enough to show resistance but not enough to be arrested. It is the coded language of a joke, the whispered poetry in a darkened room, the glance exchanged between strangers that says, I see you. The act of enduring becomes its own rebellion: a way to say, I am still here.

Hsieh and Montano’s performance was temporary, a year-long test of endurance. But in Iran, there is no end date, no moment of release. The rope remains, always present, always pulling. And yet, within this confinement, there is still movement, still breath, still life. The people of Iran, bound but unbroken, continue their silent defiance, turning mere survival into a form of resistance.

The Rise of Secularism

For decades, the Islamic Republic positioned itself as the guardian of public morality, shaping every aspect of life through its religious laws. The state claimed to define the nation’s identity, dictating how people should dress, behave, and even think. But beneath this rigid framework, something has been shifting, at first subtly, then unmistakably. Today, that shift is no longer deniable, not even by the regime itself.

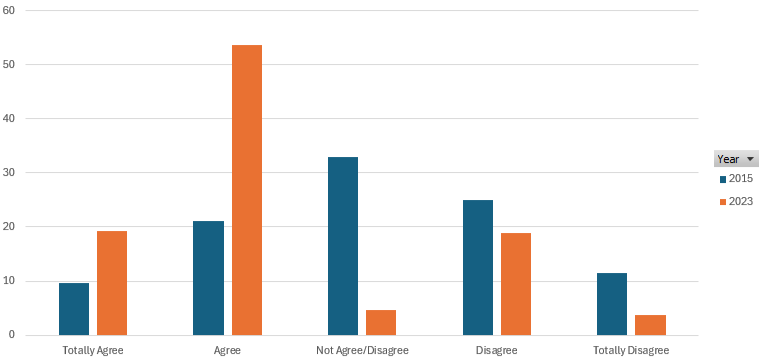

A classified government survey, conducted in late 2023 but prevented from full publication (only a portion of the survey has been made public, not the entire dataset) reveals an undeniable truth: Iranians are turning away from state-imposed religiosity at a rapid pace. The findings are staggering. Not only has support for the separation of religion and politics skyrocketed from 30.7% in 2015 to 72.9% in 2023, but attitudes toward religious practices and symbols, particularly the hijab, have undergone a transformation that would have been unthinkable just a decade ago.1

The Collapse of Hijab Enforcement

The most politically explosive revelation from the report concerns the mandatory hijab. For years, the regime presented the hijab as a red line, a non-negotiable pillar of its Islamic identity. Women who refused to comply faced warnings, fines, arrests, and brutal crackdowns. The government attempted to justify its enforcement by claiming that public sentiment supported it. But its own survey contradicts that claim.

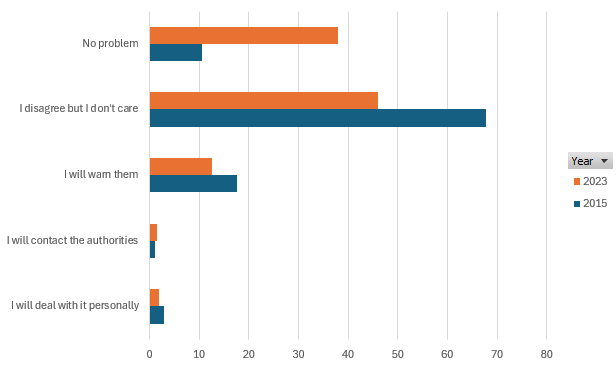

In 2023, 38% of respondents said they had no problem with women unveiling entirely. This is a radical departure from 2015 when only 10.6% held this view. In other words, in less than a decade, the proportion of Iranians explicitly rejecting mandatory hijab has nearly quadrupled.

Even among those who personally opposed unveiling, 46% stated that while they disagreed with the practice, they would not interfere in a woman’s choice. Only 12.5% of respondents said they would warn a woman to wear a hijab, a sharp decline from 2015 when 17.6% said they would actively confront women over improper hijab.

Beyond these numbers lies an even more significant cultural shift: hijab enforcement is no longer a social issue; it is purely a state issue. The government is waging a losing battle against an increasingly indifferent public. The hijab is no longer seen as a symbol of morality but as an instrument of oppression.

This rejection is not passive. The most visible act of defiance in Iran today is a woman walking through the streets unveiled. These women, who would have faced immediate arrest just a few years ago, now move through public spaces in growing numbers. Some are harassed by authorities, some are detained, but they return. The public’s response is telling: they are not confronted, not shamed, not stopped by ordinary citizens. Even among those who personally favour hijab, most have abandoned the idea that it should be enforced.

The generational divide is also evident. Education plays a decisive role in shaping attitudes toward unveiling. The survey found that nearly half (47%) of university-educated respondents found unveiling acceptable, while only 14.7% of illiterate individuals and 16.2% of those with only primary education shared this view. This contrast is critical: the younger, more educated population is overwhelmingly rejecting the state’s religious mandates, while resistance to change is concentrated among the older and less educated.

The government’s attempt to conceal these statistics reveals its desperation. The numbers expose the truth: the hijab is no longer a moral consensus. It is a political imposition that is being rejected, not just by young activists, but by a large and growing segment of society.

The Rise of the Non-Religious Majority

Beyond the hijab, the survey lays bare another fundamental shift: religion itself is in retreat. Not just in practice, but in belief. For a regime built on the notion of divine legitimacy, this is a crisis of survival.

According to the survey, 85% of respondents stated that religiosity in Iranian society has decreased over the past five years. Only 7% believed that Iranians had become more religious. More significantly, 81.8% predicted that religiosity would continue to decline in the next five years.

This pessimism is reflected in personal practice. The percentage of those who consider themselves highly or very religious has dropped to 42.6%. Meanwhile, 24.3%—nearly a quarter of the population—explicitly identified as not religious at all or only slightly religious. Another 23.2% described themselves as moderately religious, further blurring the traditional divide between devout believers and secular individuals.

The most striking evidence of this shift is in religious practice.

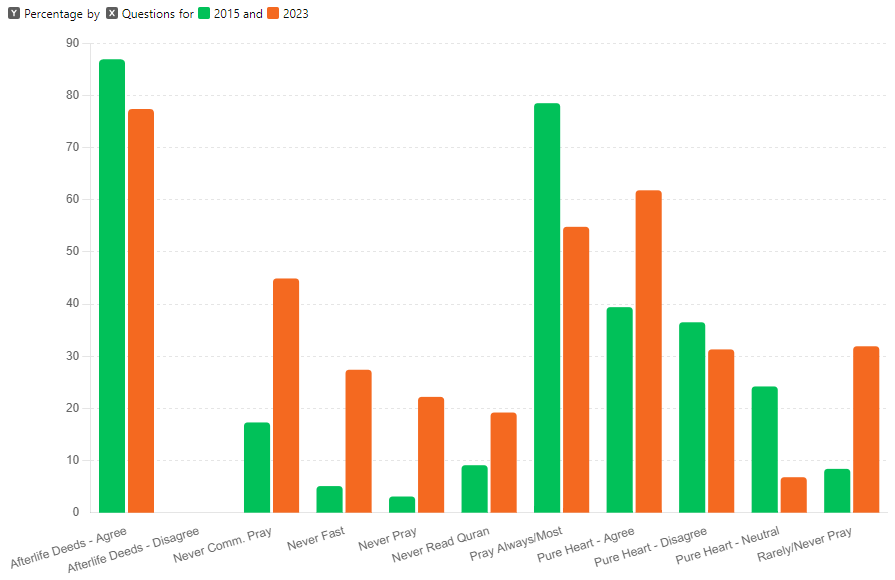

- The percentage of Iranians who say they pray ‘always’ or ‘most of the time’ has dropped from 78.5% in 2015 to 54.8% in 2023.

- Those who say they rarely or never pray increased from 8.4% to 31.9% over the same period.

- The number of people who openly stated that they never pray surged from 3.1% to 22.2%—a sevenfold increase.

- The share of individuals who said they never fasted during Ramadan rose from 5.1% to 27.4%.

- Those who said they never read the Quran climbed from 9.1% to 19.2%.

These numbers mark an extraordinary transformation. A regime that once sought to enforce religious uniformity is now governing a population which includes many people who are simply walking away from faith altogether.

One of the most telling indicators of this shift is the response to the statement, Religiosity is about having a pure heart, even if one does not pray. In 2015, 39.4% of respondents agreed. By 2023, that number had jumped to 61.8%. This means that even among those who still identify as religious, fewer and fewer people define religiosity in traditional terms.

Belief in an afterlife has also declined. In 2015, 86.9% of respondents agreed with the statement that people’s good and bad deeds are accounted for in the afterlife. By 2023, that number had dropped to 77.4%.

What emerges from these statistics is not just a decline in religious observance, but a deep and growing scepticism about religious authority itself. This is not a subtle shift. It is the collapse of a worldview that the regime spent four decades trying to impose.

The State’s Silent Panic

The government’s decision to keep this report classified and prevent its ‘full publication’ is itself an admission of failure. If these trends had supported the regime’s narrative of a pious society, the survey would have been widely publicised. Instead, it was hidden, leaked only in fragments, its findings too dangerous to acknowledge.

What makes these results so threatening is not just the numbers themselves, but what they represent. Iranians are not simply rejecting state-imposed religious rules; they are questioning the legitimacy of religious governance itself. The core claim of the Islamic Republic—that it rules by divine authority—is eroding.

The more the regime enforces hijab laws, the more it alienates the public. The more it punishes religious dissent, the more it exposes its own fragility. Every woman who walks unveiled, every young person who stops praying, every voice that refuses to repeat the state’s slogans is a crack in the foundation.

The statistics confirm what the streets have already shown: the shift away from religious rule is not a distant possibility. It is already happening. The government can suppress protests, it can jail activists, it can double down on enforcement, but it cannot make people believe.

The Breaking of the Rope

The Iranian regime has long relied on two forces to maintain its grip: faith and fear. Faith was the justification, the divine armour shielding its rule from challenge. Fear was the enforcement, the ever-present rope tightening around the people’s throats. But now, the rope is fraying. The fear remains, but the faith is gone. And without faith, the regime stands exposed, just another dictatorship, no different from the countless others that have fallen before it.

The shift away from religion is not just an abstract ideological change, it is the undoing of the regime’s foundational myth. The moment people stopped seeing the government as a sacred authority, it became just another oppressor. The moment they saw the clerics not as representatives of God, but as corrupt men clinging to power, the spell was broken. The government’s own surveys confirm it: the mosques are emptying, religious laws are ignored, and the very idea of an Islamic state is being rejected by the very people it was supposed to save.

And yet, the regime persists, desperate to tighten its grip even as it feels the people slipping away. It enforces the hijab with greater brutality, hoping to reverse a cultural shift that can no longer be controlled. It arrests journalists, artists, activists—anyone who dares to speak too freely. But these acts of repression only confirm what Iranians already know: the government is weak. A system that depends on violence to sustain itself has already lost.

This is where survival itself becomes resistance. In the past, people learned to navigate the regime’s rules like an artist maneuvers within the constraints of a performance. They mastered the art of endurance, knowing when to speak, when to be silent, when to step forward, when to disappear. But endurance is no longer enough. The new generation is not content to survive; they want to break free.

The endurance of the past was like Hsieh and Montano’s performance, a life spent within an invisible boundary, always aware of the rope, always finding ways to stretch it without breaking it. But today’s Iran is different. The rope is not just being stretched; it is being cut. The young women walking unveiled, the men who no longer bow their heads in prayer, the families who choose silence over sermons—these are no longer performances of adaptation. They are rejections of the stage itself.

The people of Iran have spent decades surviving within the ropes of oppression. Now, they are beginning to imagine life without them. And once people stop believing in their chains, once they realise that the ropes that bind them are not unbreakable, history becomes inevitable. The massive protests over the death of Mahsa Amini were an expression and intensification of this pre-existing and unstoppable wave of resistance.

The regime may tighten its grip, but the more it pulls, the closer it comes to snapping the very rope that has held it together for so long.

- The tables in this essay are based on information published by domestic media that had access to part of the survey documents. All data used in the article comes from what they published. ↩︎

Find more reporting and analysis by Siavash Shahabi at The Fire Next Time.

Related reading

The ‘Women’s Revolution’: from two activists in Iran, by Rastine Mortad and Sadaf Sepiddasht

No Hijab Day, 1 February: Confronting Misogyny, by Maryam Namazie

Confronting identity politics, a breeding ground for division and dehumanisation, by Maryam Namazie

Image of the week: celebrating the death of Ebrahim Raisi, the Butcher of Tehran, by Daniel James Sharp

The hijab is the wrong symbol to represent women, by Khadija Khan

Iran and the UN’s betrayal of human rights, by Khadija Khan

Rap versus theocracy: Toomaj Salehi and the fight for a free Iran, by Noel Yaxley

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate