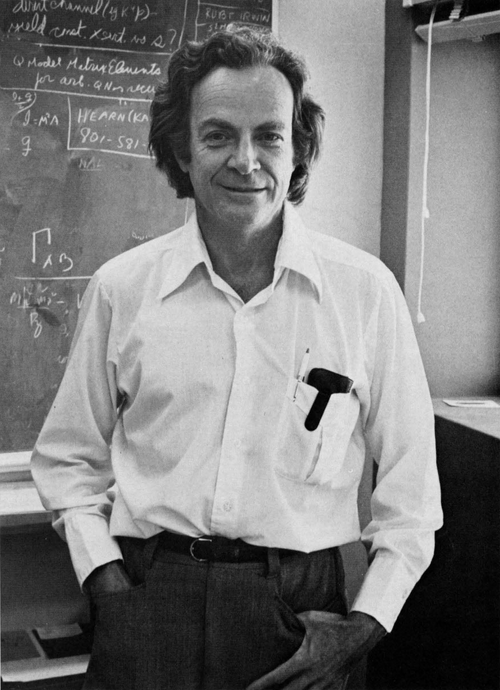

Richard Feynman is 100% my favourite scientist of all time (and I have many favourites). The Nobel Laureate was a master of the turn of phrase, and his immensely popular lectures on physics are still enjoyed today. Feynman was as anti-establishment as one could ever be, and as such was no fan of religion.

In his phenomenal interview with the BBC’s Horizon programme in the early 1980s, he pointed to the wonder of the universe, the vastness of space, and the incredible leaps made in physical science during his lifetime. For him, God was too small an idea to encompass all this.

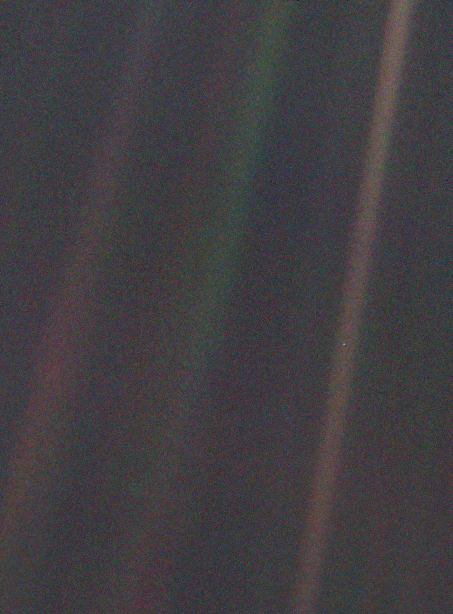

This was a time when the moon landings were still fresh in the memory and Voyagers 1 and 2 were in the throes of their ‘grand tour’ of the solar system, delivering their first photographs of the outer planets. A little later came Carl Sagan’s famous ‘Pale Blue Dot’ statement, inspired by Voyager 1’s incredible 1990 photo of the Earth, seen hanging as a tiny blue dot in a ray of sunlight from nearly 4 billion miles away. Sagan remarked on the arrogance of humanity to think itself so great and so significant in the face of this remarkable image. The Pale Blue Dot became one of the most reproduced images of the twentieth century and helped change our perspective on our place in the cosmos. (Incidentally, perhaps the most reproduced image was Bill Anders’ 1968 Earthrise photo taken from the Moon’s orbit during the Apollo 8 mission. This was indeed an incredible period of perspective-altering images of Earth in space.)

Feynman did not suffer fools. He had little patience for intellectual laziness or inconsistency and was known to be a relentless pursuer of truth with a singular contempt for untidiness of thought. All this was most dramatically shown when he clashed with NASA executives as part of the Space Shuttle Challenger investigation. During the investigation, he performed a demonstration using ice water, a rubber O-ring, and a simple clamp to show the failure of the shuttle’s solid rocket booster seal when faced with cold temperatures. In doing so, he showed up NASA’s own failure at understanding risk management. Broadcast live on national television, it was as simple and conclusive a scientific demonstration as one could imagine.

What Feynman modelled during his life was the power of clear, big thinking against the failures of small thinking. He showed that incredibly difficult problems, such as quantum electrodynamics (QED), can be solved with clarity of thought alongside hard work. Satisfaction with dead ends and non-answers should be rejected with venom. Pursue the truth to its end and search for the best answers possible. Along with all his scientific accolades, Feynman’s legacy is to have shown the power of relentless and fearless thinking. He is the model of the curious scientist who really lived by his creed: ‘the pleasure of finding things out’.

A scientific mind is a curious mind bent towards problem-solving. This mindset is present in children and is often beaten out of them by casual distraction, poor education, or bad role models. Most of us want to learn but we gradually lose this instinct as we grow up. Bertrand Russell once quipped that ‘most people would die sooner than think—in fact they do so’. Slightly uncharitable, perhaps, but the quip contains much truth. One cure for the deadening imposed on us as we grow up is the experience of an inspiring teacher. There is a good reason why Feynman was one of the most popular lecturers at Caltech. His lectures can still be bought today and are an exemplar of outstanding teaching on some of the most difficult areas of physics.

Feynman’s keen respect for nature is a lesson all can admire, religious or not. He famously noted that ‘nature’s imagination is far greater than man’s’. A proper perspective on the natural world is achieved when we look up, and deeper, at it. At the end of his appendix to the Challenger investigation he cautioned that ‘For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.’ We, on the other hand, can very easily be fooled by nature when we lack a healthy respect for it, or when we approach it with our heads down, as Feynman believed the religious do. The key to avoiding this mistake is doubt. Doubt is a core component of scientific practice—a certainty that we have incomplete knowledge and must think twice before assuming we have the answer. There is, however, a difference between the radical sceptic and the healthy sceptic, and no one modelled the latter more successfully than Richard Feynman.

In the Horizon interview, Feynman explained his problem with religion thusly: ‘I can’t believe the special stories that have been made up about our relationship to the universe at large because they seem to be too simple, too connected, too local, too provincial… One of the aspects of God came to the Earth, mind you! And look at what’s out there!… It isn’t in proportion.’

Feynman well knew that a small world comes from a lack of intellectual curiosity. To live up to him, we must not close off investigation by invoking God to fill the gaps, and we must not stop in our pursuit of truth. For a polymath like Feynman, even winning the Nobel was unsatisfying. We can all learn from his voracious pursuit of knowledge.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate