After being held in detention for nearly two years, Mubarak Bala, the President of the Humanist Association of Nigeria (HAN), was arraigned before the High Court of Justice of Kano, in Nigeria’s Muslim-majority north, on 1st February 2022. At his bail hearing, which is now forthcoming, his legal team is planning to apply for permission to have his case transferred from Kano to Abuja, the federal capital. They believe he is likelier to receive a fair trial in a cosmopolitan centre like Abuja than in Kano, where there is a ‘history of the Islamic mob pressuring…officials to convict those accused of blasphemy,’ according to Leo Igwe, founding member of HAN and leader of the campaign to free Bala. If the application for transfer is refused, the trial will proceed before the Kano court.

This article provides an update on Bala’s situation. I spoke via Zoom and email to Leo Igwe and to Amina Ahmed, Bala’s wife and mother of his son, Sodangi.

Update on the update – 25th March 2022

This article was first posted on 19th March. It was removed on 21st March at the request of Humanists International, on behalf of Bala’s legal team. It is now being reposted with the removal of information which the lawyers fear might endanger Bala’s safety, including the dates of the bail hearing and trial, the name of the prison in Kano where he has been held for over a year, and the list of the ‘blasphemous’ statements with which he is being charged. (The Freethinker had not previously been informed that posting this material might affect Bala’s situation.) According to Emma Wadsworth-Jones, Humanists At Risk Coordinator,

‘The information contained on the dates of the hearing is sensitive and could put the lives of Mubarak and his legal team in jeopardy. The dates of the hearing have purposefully been withheld to prevent vigilantes in Nigeria from taking matter into their own hands. Additionally, the publication of the text of his posts…before the hearing is liable to inflame already high tensions.’

The request demonstrates just how perilous Bala’s situation is, both for him and even for his lawyers, as long as he remains in Kano. The article below gives further details about how difficult it is to be a non-Muslim in northern Nigeria. It also considers why Bala might have annoyed the authorities so much – not just through mocking and criticising certain beliefs and practices of Islam on social media, but through inspiring a sort of humanist awakening.

It is with a heavy heart, however, that I have removed the text of Bala’s ‘blasphemous’ posts. The Freethinker has a long history of resisting censorship of supposed blasphemies. It is a matter of pride that our first editor, G.W. Foote, went to prison in England for using satire to question Christianity in this very paper.

For several years now there has been a trend, not just in Nigeria but also in Europe, of silencing those who dare to criticise Islam, or even show materials criticising it – one might think of Charlie Hebdo or Samuel Paty in France, as well as the Batley Grammar teacher in England, whose very identity has been erased from the public record.

It is ironic that the ‘blasphemous’ statements which Bala made of his own free will, and for which he has been suffering for nearly two years, must be suppressed by those defending him, because they fear that republishing the statements before his trial would provoke his opponents into further acts of aggression and injustice. Where will all this end?

Arrest and detention

Bala has been detained, on the charge of blasphemy in relation to some Facebook posts, since 28th April 2020. On 28th April, he was arrested and put in a police cell in Kaduna state; on 30th April, he was transferred to to the State Police Command in neighbouring Kano, where he was held in solitary confinement and incomunicado. At some point thereafter he was transferred to a prison in Kano State. He was not able to meet with a lawyer until October 2020. After a series of legal battles, a judge in Abuja, the federal capital, granted an application for Bala’s immediate release on bail on 21st December 2020. (The order for release on bail can be viewed towards the bottom of this report by the Foundation for Investigative Journalism.) However, he was not released. Formal charges against him were only issued on 3rd August 2021. While in prison, he was, in September 2021, denied access to medical treatment for high blood pressure. Humanists International have provided him with legal support, and maintained a record of his case as it develops.

The effect of prison

Neither Igwe nor Bala’s wife, Amina Ahmed, was able to attend the arraignment. However, according to one source, provided on the condition of anonymity, Bala ‘looked emaciated…he has not been well taken care of.’ The conditions in the prison are ‘awful’, says Ahmed. Her husband has had difficulties in accessing not only healthcare but even food while in prison. ‘Our prison service has a history of not just poor treatment, but also in terms of denying people who are detained their basic rights,’ says Igwe. The Humanists wrote to the director of prisons, as well as to Nigeria’s National Human Rights Commission, to try to ensure that the necessary treatment was provided to Bala. Over such a long period, however, it was difficult to keep up the pressure on the authorities consistently. ‘Immediately there’s no pressure,’ says Igwe, ‘The whole thing goes back to the status quo.’

How Bala’s detention has affected his family

Mubarak Bala and Amina Ahmed were married in August 2019. Ahmed gave birth to Sodangi in Abuja in March 2020, just six weeks before his father was arrested. She had just arrived home from hospital, and was still recovering from a caesarean section and postpartum trauma, when Igwe called her to say that her husband had disappeared. At first she did not believe it. ‘I said, maybe they are going to release him that evening, or after some days.’ In the event, it was eight months before she was able to see him – in prison.

The nearly two years have been an ordeal. To start with, there has been the uncertainty of not knowing what will happen to Bala. In addition, the stigma associated with being an atheist is such that Ahmed has only felt able to tell a few of her closest friends what she has been going through. She worries that other colleagues will be ‘judgemental’ rather than sympathetic, and will take the view that her husband ‘should be tried like everyone else, if he offended anyone.’

Sodangi has hardly seen his father in the first two years of his life. When his mother took him to visit Bala in prison in November 2021, she says, ‘he was just staring at his father and he didn’t allow him to touch him. He was just running away from him and was crying.’ At home, her mother has moved in to help her with the baby. Ahmed has also received financial support from the Humanist associations. ‘I’m so grateful because I didn’t believe that Mubarak and I would feel loved like this.’

Both Ahmed and Bala were brought up in traditional Muslim families. These days, she too identifies with humanist values, ‘like not discriminating against people, not judging people based on their belief.’ It is characteristic that Bala’s own best friend from childhood should be a practising Muslim. ‘Mubarak’s situation pains him, too,’ Ahmed says. ‘He doesn’t judge Mubarak, because he knows that he is a wonderful person.’

The charges

The charges against Bala were brought on an application by the Chief State Counsel of Kano State Ministry of Justice on behalf of the Attorney General. The charge sheet, which is dated 23rd June 2021, and was made available to the Freethinker, lists ten separate ‘heads of charge’ against Bala. (We cannot comment on the accuracy of these allegations.)

All the heads of charge involve posts that Bala is said to have made on his Facebook account in April 2020. These posts, the prosecution alleges, contained a total of five distinct statements that supposedly blasphemed against Islam. Three were in Hausa, a regional language, and two in English; some appear to have been posted more than once.

By posting these statements on social media, the prosecution alleges, Bala ‘insult[ed] the religion of Islam its followers in Kano State, calculated to cause breach of public peace and thereby committed an offence punishable under Section 210 of the Penal Code [of Kano State].’ Elsewhere on the charge sheet, the statements are described as ‘insulting the Holy Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W), the religion of Islam and its followers in Kano State which excited contempt of religious creed’ or as being ‘contemptuous to the religion of Islam’.

The Nigerian Criminal Code Act (s. 204) provides that the offence of ‘insult to religion’ is punishable by up to two years in prison. According to Amnesty International, the Kano State Code has a similar provision (the Freethinker was not able to access the Code). The matter is complicated by the fact that, in northern Nigeria, sharia law operates in parallel to customary, or secular, law.

Bala, as a non-Muslim, is being tried under customary law. On this basis, if he is convicted, the period of his past detention could be sufficient to discharge the statutory penalty. ‘But nobody knows whether that will satisfy the Islamic Establishment behind his arrest and detention,’ says Igwe. Under sharia law, Bala would potentially be liable to much harsher penalties, even up to execution.

The sharia courts in Kano do not shrink from imposing harsh penalties for blasphemy on those within their jurisdiction. This is shown by two cases from August 2020 – a few months after Bala’s arrest. A sharia court sentenced an Islamic gospel musician, Yahaya Sharif-Aminu, to death for allegedly saying that the founder of the Islamic Tijjaniya sect was ‘bigger than Prophet Muhammad’; the same court sentenced a 13-year-old boy, Umar Farouk, to ten years’ imprisonment with menial labour for using ‘foul language against God’ during an argument with a friend.

A retrial of Sharif-Aminu’s case has since been ordered, while Farouk’s conviction was overturned by a higher court. But others may not be so lucky. Even if the justice system does not harm them, there is always the risk that the mob may take matters into their own hands – which is one of the concerns in Bala’s case.

Islam in northern Nigeria

The reasons underlying Bala’s treatment in Kano are complicated. Historically, the north of Nigeria has been Muslim-majority since 1804, when the ulama (learned religious scholar) Usman Dan Fodiyo led a jihad against the Hausa kingdoms of western Africa and established the Sokoto Caliphate there. The British conquered the caliphate in the early 1900s. When they unified Nigeria as a single Colony and Protectorate in 1914, they retained a division between the northern and southern provinces. The Muslim influence in the north and the Christian influence from missionaries and other Europeans in the south, in line with colonial policy, increasingly took the place of traditional religions – at least officially. Nigeria achieved independence in 1960; however, the historic divisions between Muslim north and Christian south persist.

The reality, says Igwe, is that ‘you cannot oppose Islam and succeed politically in the north.’ Not only are the political elite themselves Muslim, but in one way or another, they all ‘draw their political base from the ulamas and from the religious establishment.’ Indeed, it would be ‘political suicide’ for them to go against the ulamas’ dictates. ‘And so the ulamas would be the ones who would be saying that Mubarak Bala should have a serious punishment.’ Bala’s own father is an ulama. In 2014, he had his son placed in a psychiatric ward, where he was detained against his will for 18 days, in order to supposedly ‘cure’ his atheism. It is understood that the two are still estranged.

A humanist ‘awakening’ in northern Nigeria

Before his arrest, Bala worked as an engineer for an electricity company in Kaduna, commuting in from Abuja, the federal capital, where he lived with his wife. He spent his spare time campaigning and trying to raise awareness of ‘the excesses and extremism that are embedded in the Islamic religious practice in northern Nigeria,’ says Igwe. ‘He was trying to lead an awakening of the people.’ Bala worked particularly hard to ‘mobilize young people and get them to begin to openly express critical views with regard to religion, Islam, jihad, Boko Haram, and the very disturbing way religion mixes with politics and with every other aspect of life in the region.’ He held face-to-face meetings, but was increasingly moving to online campaigns because of the risks of ‘hostility’ associated with personal appearances.

Bala’s championing of atheism and humanism was having some success, especially on social media. A 2018 report by Al Jazeera claimed that atheism, although still largely an ‘underground movement’ in Nigeria, was ‘increasingly reported among millennials.’ Bala was the only atheist interviewed who was willing to let Al Jazeera use his real name. ‘When he was arrested,’ says Igwe, ‘Somebody called me on phone and told me that there were thousands of [atheists] in Northern Nigeria, and many of them were actually finding a voice. They were finding a platform based on what Mubarak was doing.’

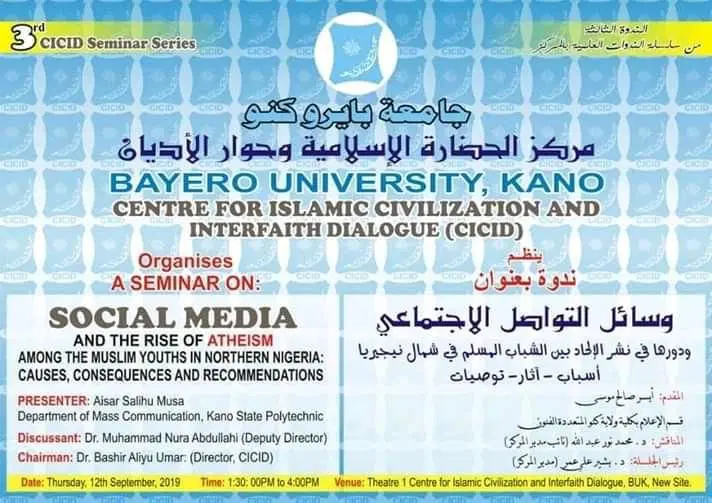

Bala’s success was the problem. ‘They [the Islamic authorities] just don’t like that name, “atheist”,’ says Igwe. ‘It invokes a lot of anxiety and hostility in people.’ There was sufficient concern about the atheist movement that on 12th September 2019, as Igwe reported in The Maravi Post, three academics held a seminar at Bayero University, Kano, on ‘Social media and the rise of atheism among the Muslim youths in northern Nigeria: causes, consequences and recommendations’.

Although the seminar was held at the ‘Centre for Islamic Civilization and Interfaith Dialogue’, as Igwe pointed out, ‘it is not clear how the centre goes about the interfaith dialogue because no evidence of interfaith communications exists on their web site’ – let alone communication between believers and atheists.

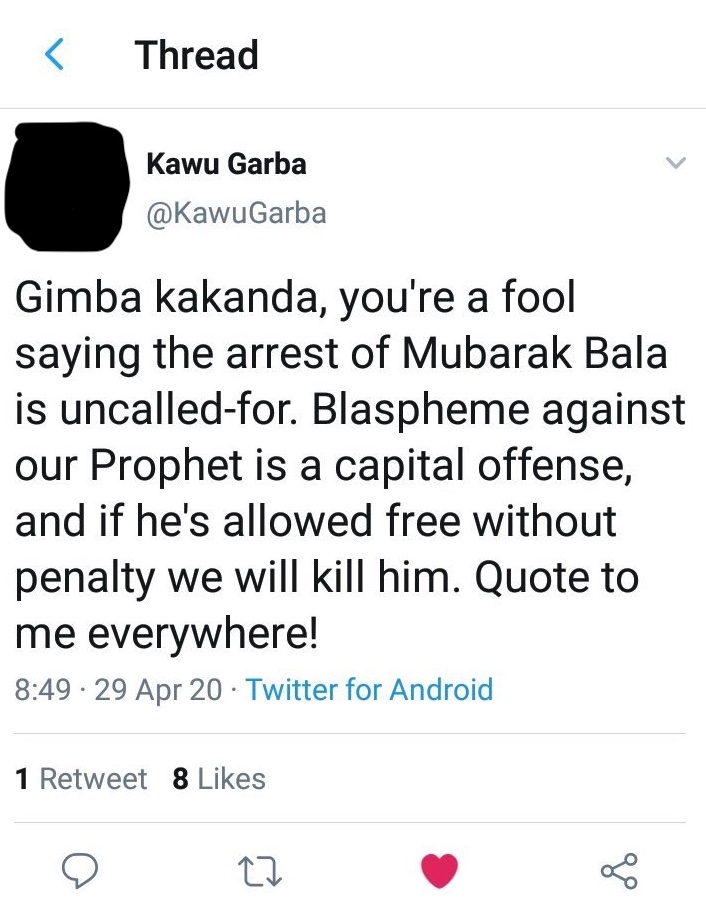

After Bala’s imprisonment, Igwe recalls, there was a sense of ‘relief across the Islamic community.’ His opponents took to social media to celebrate his punishment. Twitter posts carried vicious messages. ‘Blaspheme against our Prophet is a capital offense,’ wrote one user calling himself Kawu Garba, ‘And if he’s allowed free without penalty we will kill him.’

Despite the unlawfulness, not to say inhumanity, of Bala’s treatment by the secular authorities, there was a deafening silence from the religious contingent. ‘No one in his local area in Kano has called for his release,’ says Igwe. ‘I think that they’re silent because they have accomplished their goal.’

‘Insulting religion’

On the face of it, Bala is being prosecuted for a pure crime of words, which do no harm to any living individual or any identifiable group. It is bad enough that ‘insulting religion’ is an offence on the Nigerian statute book; the Kano authorities seem to have pursued Bala with vindictiveness as well as utter disregard for due process. In all the circumstances, it seems clear that they perceive social media posts as a real threat to the authority of Islam in their region.

Even in countries where insulting religion is not (for now) a crime, this charge is often made against people who mock religious ideas or practices that they consider absurd. ‘Insulting a religion’ is also speciously equated with the nebulous charge of insulting the worldwide population of its adherents. In the UK, this kind of rhetoric was used in the Batley Grammar case.

As the detention of Mubarak Bala shows, to criminalise speech about a controversial subject – whether religion or anything else – is to hand power to those who want to impose their views on others. Those who have reservations about free speech in countries like the UK might ask themselves what they would do in Bala’s position.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate