In our second feature for Secularism Month, Stephen Evans, CEO of the National Secular Society, argues for the vital importance of free speech in a liberal democracy, and considers the place of this fundamental right in the secularist tradition from the nineteenth century to the present.

‘Without free speech no search for truth is possible; without free speech no discovery of truth is useful; without free speech progress is checked…Better a thousand-fold abuse of free speech than denial of free speech.’

So said Charles Bradlaugh, the radical politician, freethinker, and founder of the National Secular Society, in a speech at London’s Hall of Science over 150 years ago. His words are still profoundly relevant today, as societies and legislators grapple with the concept of free speech and where its limits should lie.

The human impulse for free thought and speech has, throughout history, clashed with religious sensibilities, and religious conservatives have consistently sought to stifle debate, criticism and mockery of their beliefs.

‘Cancel culture’ may seem like a modern phenomenon, but the ostracism faced by those who dare to speak against the prevailing orthodoxies of the day is nothing new. After being elected as MP for Northampton, Bradlaugh was prevented from taking his seat for many years on account of his well-known atheist views and broadsides against religion.

Religion’s political influence has resulted in blasphemy laws that criminalise insulting or showing contempt for ideas which are deemed sacred. Around 70 of the world’s 195 countries have blasphemy laws. Penalties for violating them can range from fines to imprisonment and death.

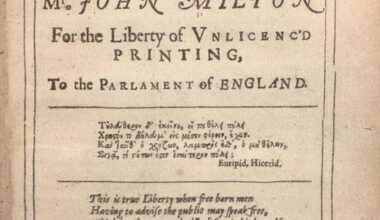

Secularists have long led the charge to abolish such laws. Charles Bradlaugh first proposed a bill to abolish the UK’s blasphemy laws in 1889. He had himself narrowly escaped a blasphemy conviction in 1882 for his assistance in producing The Freethinker. Its editor, George William Foote, was less fortunate and found himself imprisoned in 1883 for twelve months with hard labour. Once released, Foote went on to succeed Bradlaugh as President of the National Secular Society.

Decades of subsequent campaigning culminated in the common law offences of blasphemy and blasphemous libel finally being abolished in England and Wales in 2008, and in Scotland in 2021. They remain on the statute books in Northern Ireland, albeit unused. But the threat of legal impediments to free speech about religion remains.

The Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 created new offences of stirring up religious hatred. As originally drafted, the legislation would have replaced the scrapped blasphemy law with a wider-ranging prohibition that would cover not just Christianity but all religions.

A coalition of secularists and other free speech defenders had to win a hard-fought campaign to secure a vital freedom of expression clause. This ensures that nothing in the Act prohibits or restricts ‘discussion, criticism or expressions of antipathy, dislike, ridicule, insult, or abuse of particular religions, or the beliefs or practices of its adherents.’

Religious and non-religious groups alike united to successfully campaign for similar amendments in Scotland’s Hate Crime Act in 2021, which introduced several offences of ‘stirring up hatred’, including on the grounds of religion. The Act, which imposes stricter limitations on free speech about other contentious topics, such as transgender identity, has yet to be implemented. [See our discussion of this topic – Ed.]

The most restrictive speech laws remaining in the UK can be found in Northern Ireland, where ‘stirring up hatred’ offences criminalise ‘threatening, abusive or insulting’ forms of expression deemed ‘likely’ to stir up hatred or fear against religious groups, even if there is no intent to do so. The lack of a requirement for mens rea (intent), and of protections for free speech about religion, reveals a worrying disregard for freedom of expression.

Most people will accept there must be some limitations on speech – including both what they say in person and what they publish online. Laws against harassment, or incitement to commit crimes, as well as restrictions on libel or slanderous speech, are reasonable. But to put the emphasis of the law not on what has been said, but on the subjective feelings of a person who has been insulted or offended, is to ring the death knell for free speech. It is a dangerous road to go down.

Perhaps an even greater threat today comes from self-censorship: blasphemy codes which people feel obliged to impose on themselves not out of fear of breaking the law, but because of the threat of violence.

The declaration of a fatwa on Salman Rushdie, the murderous attack on the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, and other outpourings of anger and violence from conservative Muslims with hurt feelings, has highlighted a clash between certain interpretations of Islam and free speech. And it has created an impulse to protect religious sensitivities to the detriment of free expression.

The incident in Batley last year, where a teacher was forced into hiding in fear of his life after using a cartoon of Mohammed to teach about freedom of expression, revealed an unwillingness on the part of the political and media establishment to stand up to fundamentalist demands.

The outcome of a subsequent investigation was that the teacher should not have shown the cartoon. The teacher was forced out of his job and his family from their home. This was a victory for the religious bullies and essentially a capitulation to the mob. Liberal principles were sacrificed for the sake of expediency and a quiet life. The problem is that accommodations made to religious fundamentalists will bring anything but a quiet life. They simply invite further demands and create an expectation that religious sensibilities will always be protected.

Meanwhile, a well-meaning attempt to tackle anti-Muslim prejudice by promoting a flawed definition of ‘Islamophobia’, as has been proposed by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims, risks further self-censorship.

The definition of Islamophobia proposed by the APPG is that it is ‘a type of racism that targets expressions of Muslimness or perceived Muslimness’. This unhelpfully conflates criticism of Islamic practices with hatred of Muslims. It has the clear potential to chill freedom of expression, and in particular academic and journalistic freedom.

Attempts to police speech about Islam have been made at the international level. Between 1999 and 2010, a coalition of 57 Islamic nations known as the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) pushed ‘defamation of religion’ resolutions at the United Nations. Proponents argued that Muslims were facing growing intolerance and discrimination, which they described as ‘Islamophobia’. But human rights and secularist groups warned that the focus on protecting Islam rather than individuals was an attempt to impose a global blasphemy law.

The campaign by the Islamic nations faced opposition from western democracies, which argued that the ‘defamation of religion’ resolutions would violate the right to freedom of speech, thought, conscience and religion. Eventually the defamation approach was abandoned in favour of a resolution on ‘combating intolerance, negative stereotyping and stigmatisation of, and discrimination, incitement to violence, and violence against persons based on religion or belief.’

People have rights; ideas do not. The state should protect individuals, but not their beliefs. As the writer Kenan Malik argues, a distinction between people and ideas is essential both so that people may be treated equally and so that ideas may be challenged and changed.

The prevailing ‘culture of offence’, as some have called it, in which speech subjectively deemed ‘offensive’ or ‘hateful’ is considered beyond the pale, is toxic to democracy and harmful to the advancement of human rights.

The best way to foster social cohesion and preserve harmony between people of all religions and beliefs is to recognise that the freedom to question, criticise or mock religion is every bit essential as the freedom to practise religion. True freedom of religion or belief for all cannot be realised without guaranteeing freedom of expression.

Government and civil society need to send a clear message that in a liberal democracy there can be no right not to be offended. Being offended from time to time is the price we all pay for living in a free society. It is a price worth paying, because free speech means nothing without the right to offend.

Standing up for up for these liberal principles is crucial to the preservation of individual rights and freedoms. That is why promoting free speech as a positive value remains at the core of the National Secular Society’s work today.

1 comment

“The best way to foster social cohesion and preserve harmony between people of all religions and beliefs is to recognise that the freedom to question, criticise or mock religion is every bit essential as the freedom to practise religion. True freedom of religion or belief for all cannot be realised without guaranteeing freedom of expression.”

The nub of the argument but as the repeated mentions of one particular faith to illustrate points in this article shows, one particular demographic, (the Islamic one) will not abide by that principle. Their opposition is now hard baked into their legal system (sharia).

Unfortunately, our authorities fear the probable unrest that challenging those views on blasphemy will engender more than the protests against restricting free speech.

The former opposition will almost certainly involve serious violence or that threat will be continuously in the background. Against such a threat the polite protests of liberal minded thinkers are of little concern, hence, the continued growth of restrictions on what can be said, ‘protected characteristics’ will continue in legislation because it is the easier route for government.

The only way to counter this is for liberal free thinking people to stop being nice and even-handed about this very real threat to our society, take the gloves off and very clearly and openly criticise Islam as a set of ideas. I have laid out in a comment on another article:

https://freethinker.co.uk/2022/03/the-radicalisation-of-young-muslims-in-the-uk-an-ongoing-problem/

the basic tools (ECHR judgement and Council of Europe reports, resolutions) that can be used to critique Islam as a set of ideas. We now need people and organisations with bigger megaphones than my own puny voice to step up to the plate.

Concerns about tarring all Muslims, who may not believe all that sharia says, need to be put aside. They should not be regarded as a group that requires protection because Islam is a belief system, nothing more and the remedies to any stigma that criticism generates lie in their own hands. They can either work openly to change their beliefs or simply announce that they are no longer a Muslim.

Both courses of action carry risks given the Islamic law of apostasy and many attempts to change key principles of sharia carry the probability of being declared an apostate for any Muslim.

It is up to us to push hard for protecion for apostates and blasphemers (eg Batley teachers) in tandem with loud criticism of the many aspects of Islam-sharia that contravene human rights.

https://pace.coe.int/en/files/25246

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate