The ‘New Atheist’ position has been misunderstood and misrepresented since the term was coined. There seems to be something about its capacity for independent thought which makes it a perennial source of confusion.

Eighteen years after publishing The God Delusion, Richard Dawkins recently managed to surprise both conservative figures and Muslim activists by saying that he is a ‘cultural Christian’ and would choose that faith over Islam if forced.

Seeing as though he has said as much for decades—even getting a similar response to it in 2018 when comparing church bells favourably to the muezzin’s call to prayer—one wonders where these people (from Jordan Peterson to Mehdi Hasan) have been all this time.

The natural suspicion is that they were not really listening to begin with, even when they were in conversation with Dawkins, as both Peterson and Hasan have been. In any case, they have undoubtedly since been working up their respective theocratic arguments ahead of what they see as the battle for Western hearts and minds.

As such, it is not that they cannot conceive that a famed atheist might prefer the religion of his upbringing if compelled, but that this does not sufficiently convince those they hope to convince (including themselves) that he was all along a lost Christian, shortsighted iconoclast, or closeted ‘Islamophobe’—to be recruited, ignored or despised accordingly.

That the defenders of Christianity and Islam are so closely aligned here should come as little surprise. The thing about the religiously motivated is that they are often confounded by freethinkers.

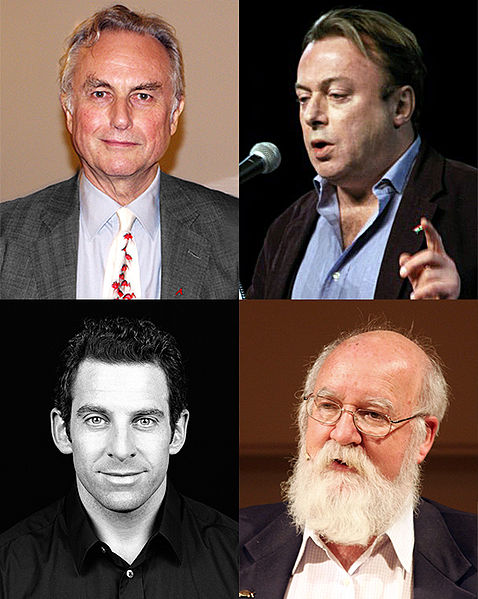

Here one is put in mind of the joke relayed by Dawkins’s late colleague Christopher Hitchens: a man is stopped at a checkpoint in Belfast and asked whether he is a Protestant or a Catholic. He answers that he is an atheist. Response: ‘Protestant atheist or Catholic atheist?’

For his part, Hitchens refused to be the butt of such a joke, preferring the more forthright, negative term ‘anti-theist’. And yet, even he was unapologetic in his gratitude for some of his Christian inheritance, from the King James Version of the Bible to the works of G. K. Chesterton. Actually, he was even willing to assent to a sort of ‘Protestant atheism’ in his love for the KJV and his respect for the Protestant tradition of resistance to Catholic authority. The point is that none of this necessitated a belief in, or even respect for, the divine.

(Likewise, his assertion that ‘the most toxic form that religion takes is the Islamic form’ did not make him a bigot or an ‘Islamophobe’, since Islam is an ideology, not a race, to be judged on its merits.)

Still, he and Dawkins, along with the two other ‘Horsemen of the Non-Apocalypse’, Sam Harris and Daniel Dennett, spent much time debating the extent to which Christianity could be credited for Western achievements. Hitchens, for instance, asserted that John Donne could not have written his poetry without piety, while the others have variously pointed out the inherent problem of exclusively acclaiming the only game in town for the works it commissioned. In other words, we will never know what Michelangelo would have produced in a secular society.

It is therefore tedious that despite such nuanced conversations (along with countless books, public debates, reiterations, and restatements), educated people should come away thinking that atheism (new or otherwise) is just another blind dogma, or the want of one.

Worse is the increasingly popular view that the only way to fill the ‘God-shaped hole’ or to combat the encroachment of Islam(ism) and ‘wokeism’ on public life is through a return to Christianity.

Of these re-conversions, the most surprising and instructive was that of the famed New Atheist and critic of Islam, Ayaan Hirsi Ali. The reasons she cites for her newfound faith in Jesus are that she missed the spiritual solace she found in religion and that uniting under the West’s Judeo-Christian tradition is the only viable bulwark against the West’s totalitarian enemies—China, Russia, Islamism, and wokeism.

The first reason demonstrates the regressive draw religion holds for those brought up in it. The capacity for lapsed believers to attempt to find ‘meaning’ in the faith of their youth, especially as thoughts of mortality begin to assert themselves, is as predictable as the age-old political shuffle to the right. But Hirsi Ali has ‘returned’ to a different faith entirely, which further suggests that any meaning has more to do with the medium than the message, and thus cannot be meaningful in any true sense. It is simply a kind of nostalgia for the little rituals, sights, smells, and consolations of religion. In short, the feeling a ‘cultural Christian’ like her friend Richard Dawkins would share.

The second reason demonstrates how quickly religion becomes the answer to everything for the born again (again). As Hirsi Ali goes on to say:

‘The lesson I learned from my years with the Muslim Brotherhood was the power of a unifying story, embedded in the foundational texts of Islam, to attract, engage and mobilise the Muslim masses. Unless we offer something as meaningful, I fear the erosion of our civilisation will continue. And fortunately, there is no need to look for some new-age concoction of medication and mindfulness. Christianity has it all.’

The argument here, then, is that to resist totalising belief systems like Islam and Chinese autocracy, we must take our lead from them and then reinstate another. It is also worth noting the suggested (if obvious) starting point: those ‘foundational texts’, which is to say the ‘fundamentals’—this being a few letters away from the approach which once had Hirsi Ali ‘cursing Jews’ from inside a burqa.

The temptation is to believe that no such thing could happen here, of course, while forgetting that the potency and unpredictability of doctrinaire wish-thinking is the very root of the problem in the first place.

Indeed, much of the concern about Wokeness comes from how much it resembles a religion, with its fanaticism and irrational articles of faith. How, then, can we argue credibly that trans women are not literally women while, for instance, maintaining that bread and wine can literally transubstantiate into the flesh and blood of an immortal Bronze Age preacher born of a virgin?

But not much less will do, according to the ‘New Theists’. Otherwise, we are just like Dawkins, who has either failed to see the light or is recalcitrant, and therefore cannot join the united ranks of Christian soldiers marching to the Culture Wars.

These are wars they will lose, of course. For there remains no proper foundation from which to make the required leaps of faith en masse. Their only real plan, it seems, is to cynically entrust themselves to a God they barely know. This, in the face of enemies whose every moment is accounted for by a set of absolutist tenets, is asking to be dragged down to their level and beaten with experience.

And yet this is a plan on which many have now embarked, inspired in part by Tom Holland’s history of the faith, Dominion. But I would submit that the New Theists’ fervour owes more to the tendency of history to repeat itself. For what are these but vague agitations for another crusade in response to an expansionist caliphate, or other? If God be for us, who can be against us? is a rhetorical question with a different answer every time it is asked.

Only through rational secularism have we ever come close to breaking this cycle. This is reflected in our language—from the Dark Ages to the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. This is not to say that secularisation has been without far-reaching implications. The same advancements which negated the need for religion as a way to explain the world have also undone respect for tradition and inherited wisdom while atomising society.

The French novelist Michel Houellebecq has been the most astute observer of this phenomenon. Especially by chronicling the post-postmodern malaise of the individual, he has managed to predict the machinations of the competing orders of Islamism and Globalism. In doing so, he has become the sage of our time, more so than Holland, which is why his apparent proposal of Christianity as an antidote has been so readily assumed.

Scepticism and intellectual rigour…are the very qualities which, now and in the coming age of Artificial Intelligence, are far more valuable against our enemies than matching their ignorance—and arrogance.

What seems to have been overlooked by those who herald Houellebecq as a Catholic thinker, however, is that even he has found it impossible to complete the conversion. In an interview with a specialist in his work, Agathe Novak-Lechevalier, he said: ‘Conversion acts as a revelation. In fact, every time I go to mass I believe; sincerely and totally, I have a revelation every time. But as soon as I leave, it collapses.’

In which case, what hope is there for the rest of us? After all, nothing less than a full-throated avowal will suffice if Christianity is to be the cure for our ills. There is no way to force belief, so all that remains is to reject the notion or deceive ourselves and those around us, which is only a disguised form of cultural Christianity anyway. And even if we were all to be smitten in some mass Damascene moment, what of its unintended consequences for scepticism and intellectual rigour? These are the very qualities which, now and in the coming age of Artificial Intelligence, are far more valuable against our enemies than matching their ignorance—and arrogance.

The problem is that such looming spectres are exactly what make past certainties seductive. As Oswald Spengler predicted, existential threats inspire a search for existential responses. This new Christian revival, then, has as much to do with a yearning for transcendence of, and salvation from, what we are menaced by as it has to do with fighting back. The urge is not to be sneered at, but likewise it should not go unchallenged when it comes at the expense of our critical faculties, especially in these critical times.

Cultural Christianity is therefore an argument for getting our priorities straight. It is an argument for recognising that religion is in fact the product of culture, not the other way around—an assumption that even the religious make for every other faith but their own.

Then we might see that just as the beauty of the ancient world can be appreciated and preserved without adoration for Zeus, Jupiter, or Osiris, so too can we extract significance from Christian holidays, art, and architecture without insulting the rational human impulses which may not have inspired them, but which surely created them.

Further reading on New Atheism and New Theism

The case of Richard Dawkins: cultural affiliation with a religious community does not contradict atheism, by Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

Do we need God to defend civilisation? by Adam Wakeling

What has Christianity to do with Western values? by Nick Cohen

What I believe: Interview with Andrew Copson, by Emma Park

How three media revolutions transformed the history of atheism, by Nathan Alexander

Atheism, secularism, humanism, by Anthony Grayling

‘An animal is a description of ancient worlds’: interview with Richard Dawkins, by Emma Park

‘Nature is super enough, thank you very much!’: interview with Frank Turner, by Daniel James Sharp

Consciousness, free will and meaning in a Darwinian universe: interview with Daniel C. Dennett, by Daniel James Sharp

Christopher Hitchens and the long afterlife of Thomas Paine, by Daniel James Sharp

‘The Greek mind was something special’: interview with Charles Freeman, by Daniel James Sharp

‘We are at a threshold right now’: interview with Lawrence Krauss on science, atheism, religion, and the crisis of ‘wokeism’ in science, by Daniel James Sharp

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate