A satisfactory apology?

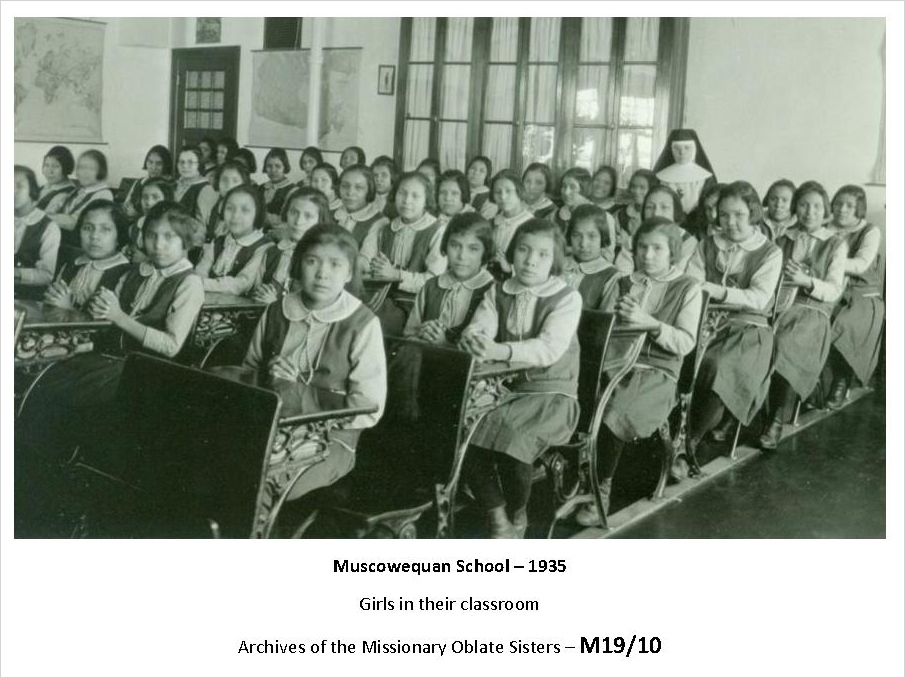

The Church of Rome has finally started to face up to some of the historic abuses committed in its name. Earlier this month, a remarkable series of meetings was held between Canadian Indigenous leaders and Pope Francis I. The latter issued an apology, in Italian, for ‘the deplorable conduct of those members of the Catholic Church’ who had participated in the abuse of the Indigenous children caught up in the government’s coercive system of residential schools between 1883 and 1996. At least 150,000 children were forced to attend the schools, and more than 4,000 died.

The long-festering scandal of the schools took on increased prominence in May 2021, when the unmarked graves of 215 children were discovered by ground-scanning devices at a former residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia. Several hundred more unmarked burial sites have since been detected at other former schools. The continuing shock of these discoveries has been such that, in the Canadian media, the five-day Rome meetings sometimes overshadowed even the war in Ukraine.

Not all those present at the meetings, however, and even fewer of those watching from Canada, were entirely satisfied with the Pope’s apology. By limiting its terms to only certain ‘members’ of his Church, the Pontiff has been perceived by some to be ducking responsibility for the failure of the institution as a whole to renounce the evils of its past.

‘His [the Pope’s] words may be what some want to hear, but there are no repercussions for what happened,’ said Gene Gottfriedson, a 58-year-old survivor of the Kamloops school and a former altar boy. ‘Forgiveness is not easy,’ wrote journalist Tanya Talaga, who is of Indigenous descent, in a response to the Pope’s apology in Toronto’s Globe and Mail. ‘Reconciliation does not stop here at the Vatican. And it will not end until we bring all our children home.’

The harm caused by the residential schools

In Indigenous tradition, harm done to an individual can extend through seven generations of their family. This has truly been the case of the school survivors. On top of the sexual and other physical abuse many suffered at the hands of their priest teachers, they were forbidden to speak their native language, were taught nothing of their tribal heritage, and emerged, in many cases, as rootless teenagers who went on to become parents without having learned any parenting skills. Associated harms include the alarmingly high rate of Indigenous prisoners in Canada’s jails: this is seven times that of other Canadians, accounting for 27 per cent of the inmate population while representing only 4.1 per cent of the Canadian population as a whole.

The so-called ‘education’ that residential school children received was heavy on Bible teaching, but proved useless in enabling its students to lead normal adult lives. After they finished school, most returned to the ‘reserves’ – inferior land set aside for Indian tribes in the 1800s – and subsisted on government welfare. They were forbidden by the Indian Act to own property, to borrow money to start businesses, or to leave the reserves without a pass issued by the local Indian agent, a government employee. (When South Africa established its apartheid system, it used Canada’s Indian reserves as a model.) Ironically, thousands of Indigenous families later became adherents of the Christian churches in which they had suffered abuse.

Truth, reconciliation and the Catholic Church

Today, the schools are viewed by most Canadians as a national disgrace and a stain on the country’s reputation as a tolerant, secular, liberal democracy. Two prime ministers, Steven Harper and Justin Trudeau, have previously apologised for them. The issue has occupied political and public centre stage since the signing of the Indian Schools Settlement Agreement in 2007. The agreement, involving the government, Indigenous organisations, and the Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian and United churches, led to the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which heard 6,500 witnesses and in 2015 issued a report containing 94 ‘calls to action.’

Every denomination has since met their obligations to provide reparations and assistance to surviving Indian school residents and their descendants – except the Catholic Church, which operated about 70 per cent of the 130 schools.

Under the Schools Settlement, most of the $4.7 billion (£2.9 billion) paid to survivors of the schools and their families came from the Canadian federal government. Together, churches and dioceses of the Catholic Church in Canada pledged $54 million in various cash donations to compensate survivors, plus an additional $25 million in services in kind. In the event, they fell seriously short in their promises – despite the fact that cash reserves, property and other valuables owned by the Church in Canada amount to billions of dollars, making it reportedly ‘Canada’s largest charity by far’.

Shamefully, the federal government let the Church off the hook to the tune of millions of dollars, because, according to government lawyers, there was little chance of recovering the funds through a lawsuit. However, in an apparent response to mounting pressure following the recent discoveries, the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops last year announced plans for a second fundraising campaign for survivors of the schools; this is still in progress.

The residential schools and secularism in Canada

For all the furore over the visit to Rome and the Pope’s response, most commentators have overlooked the consideration that the harm done to Indigenous children would have been largely avoided if Canada had required a secular education to be provided in its Indian residential schools.

The residential school system was intended to be managed by the Catholic and Anglican churches. In 1879, just as it was being finally approved, George Jacob Holyoake, the British secularist and coiner of the term ‘secularism’, met with the Canadian prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, over lunch in Ottawa. While the record is silent on this issue, Holyoake would, one imagines, have cautioned Sir John on the adverse effects he had observed in England on schools that retained religious management of their classes and curriculum.

Any advice that Holyoake may have given ultimately fell on deaf ears. The schools, set up to ‘take the Indian out of the child,’ ignored every principle of secular education that had been provided by the public school systems since 1867, when Canada became a self-governing Dominion of the British Empire.

Canada’s failure to adequately anchor its laws and institutions in secularism has led to tragedy, persecution and indifference. It has harmed generations in the 160 years since Confederation and has delayed the development of a clear national identity. There are still a number of anti-secular legislative provisions in force in Canada, including the public funding of Catholic schools and tax exemptions for churches. While humanist and secular societies in Canada have campaigned to abolish such provisions, they have so far made little progress.

The Canadian Constitution Act, created in 1982 out of the old British North America Act, flies in the face of secularism in its declaration that Canada ‘is founded upon principles that recognize the supremacy of God’. The Fathers of Confederation saw Canada as a constitutional monarchy in which the monarch, whether Queen Victoria in 1867 or Queen Elizabeth in 2022, would reign as both Head of State and ‘Defender of the Faith’ – the ‘faith’ being that of the Church of England.

Despite such legal provisions, many Canadians appear to go about lives that are largely secular. According to a recent study, ‘Religiosity in Canada and its evolution from 1985 to 2019’, the share of people who reported having a religious affiliation fell from 90 percent in 1985 to 68 percent in 2019. Those who attended a religious activity at least once a month dropped from 43 to 23 per cent. The jettisoning of religious affiliation and the growth of secular sentiment in Canada go a long way to explaining public indignation over the failure of the Catholic Church to atone for its mistreatment of Indigenous children.

The Pope is expected to visit three Canadian cities in July – Quebec City, Edmonton, and Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavit in northern Canada. According to CBC News, ‘the delegates who travelled to Rome expect Pope Francis to deliver a fulsome apology on Canadian soil for the church’s role in running residential schools.’

Demands that he recognise the Catholic Church’s institutional failures are likely to increase as the visit draws near. Will Francis show true contrition, and will he provide just compensation for the victims? As far as many Canadians are concerned, he has a long way to go – spiritually as well as geographically.

1 comment

It seems to me that only the religious can get away with such abuses and I guess this is because there is a widely held assumption that despite the evidence to the contrary religion does good?

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate