In the late 1880s, Walter Richard Sickert (1860-1942) was an emerging artist who made money from portrait painting. Ellen Cobden, Sickert’s first wife, was one of the five daughters of Richard Cobden, the great free trade advocate. Through Cobden, Sickert made contact with many leading liberals who knew and admired Charles Bradlaugh (1833-1891). In about 1889, he painted a portrait of Bradlaugh in his later years. This was exhibited in and then purchased by the National Liberal Club; it is still on display in their clubhouse on the Embankment. (Bradlaugh was initially rejected by the NLC when he applied for membership in 1882; he eventually joined in 1890.) This painting helped to cement Sickert’s growing reputation.

Bradlaugh greatly impressed Sickert and shared his iconoclasm. When Bradlaugh died in 1891, Sickert was commissioned by an anonymous Manchester freethinker to paint a posthumous portrait of him standing at the Bar of the House of Commons, demanding to take his seat as an MP after his entry had been blocked by opponents hostile to his atheism and republicanism. The largest painting that Sickert ever produced, it was displayed in the headquarters of the Manchester branch of the National Secular Society, and later transferred to the Manchester Art Gallery, where it is still on display.

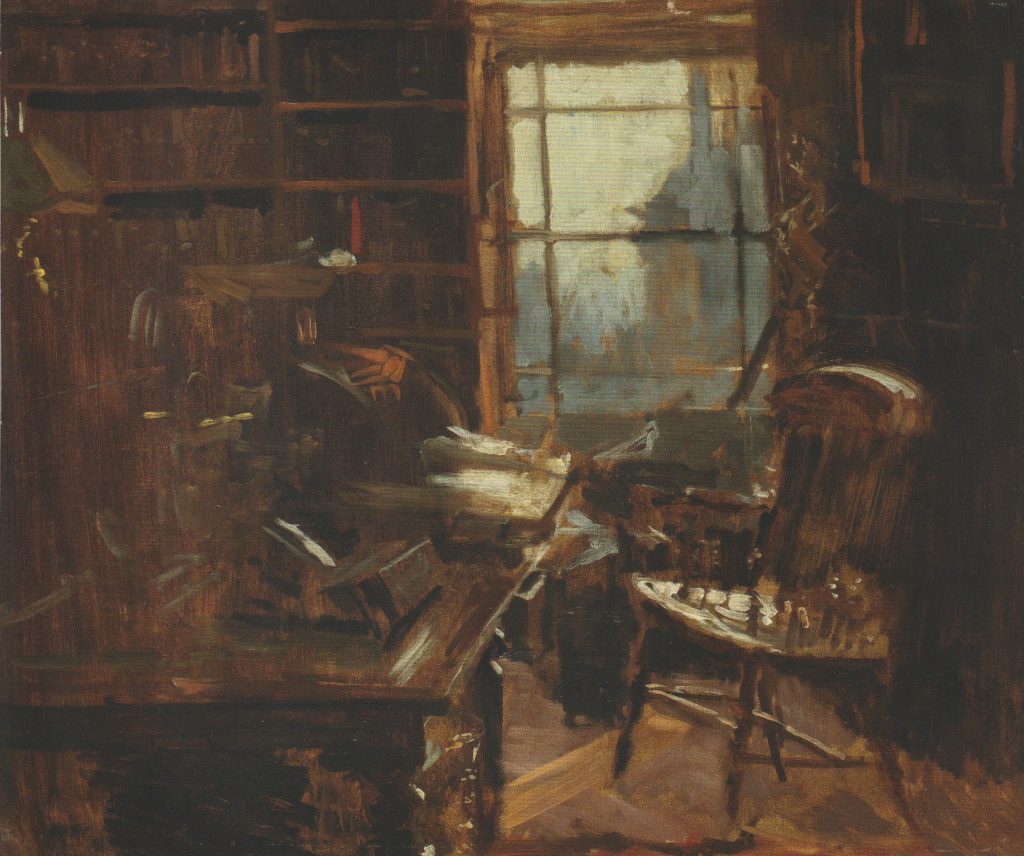

After Bradlaugh’s death, Sickert offered to paint a picture of his study at his home in St John’s Wood – a rented flat over a piano shop – for his surviving daughter, Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner. In 1890, Sickert had made a cartoon sketch of the same study with Bradlaugh in it; by this stage, he had almost become Bradlaugh’s ‘official portraitist’. The painting of her father’s empty study was presented and dedicated to Hypatia.

In this painting, the only source of light comes from the sky outside, which falls onto Bradlaugh’s empty chair. The chair appears to have been left pushed out – as if abandoned halfway through a task – and lies just below a blurred bust, like the shadow of the man who has gone. Otherwise, the interior is packed with books in innumerable shades of brown. A green and brass reading lamp suggests relentless effort late into the night, while streaks of white evoke a sheaf of papers and a quill pen, lying on the desk as if about to be used. The view out of the window is of the city where Bradlaugh lived most of his life.

The painting also alludes to Hypatia’s perspective as her father’s former secretary and companion in his struggles. It remained in her possession until her death in 1934; since then, it has been owned by a series of private collectors.

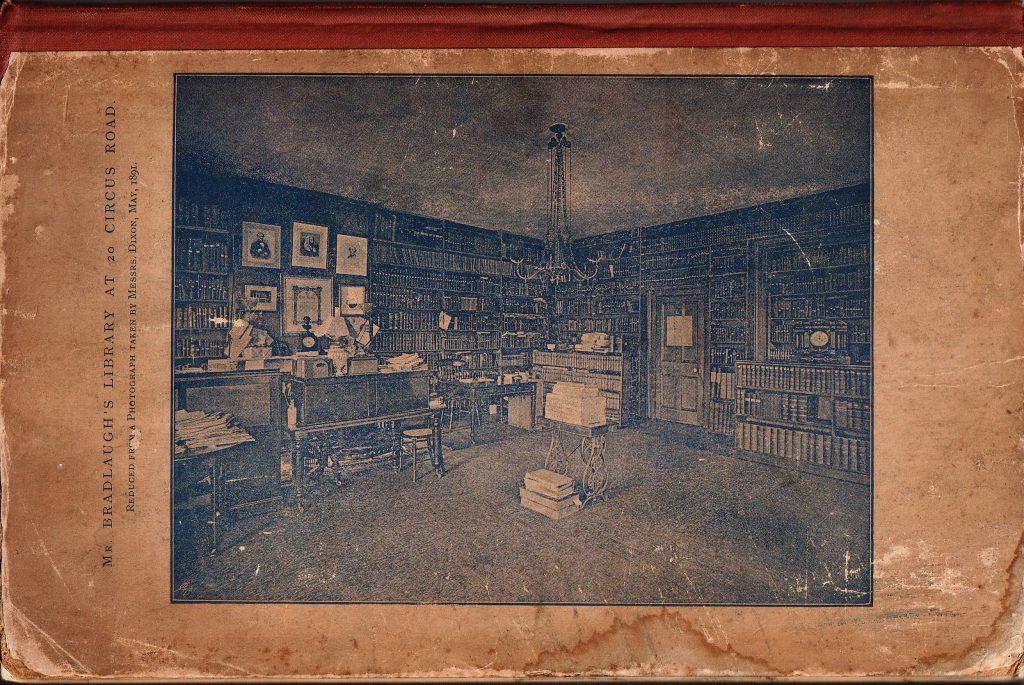

Comparison with a photograph of the study published in the same year (below) shows the reality behind Sickert’s painting, and the ways in which he drew on what was there but also imbued it with his own interpretation of Bradlaugh’s personality and presence.

1 comment

I find this article and selection of paintings both stunning and informative. Excellent work!

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate