George William Foote was born in Plymouth in humble circumstances on 11 January 1850. His father died when he was young, but he had a good education by the standards of the time. This stimulated his interest in literature. He was brought up an Anglican, but by the age of 15 was drawn to Unitarianism.

In 1868 he moved to London, first working as a librarian. He soon encountered secularists and became active in the movement; he was primarily drawn to George Jacob Holyoake and his more moderate version of secularism, rather than Charles Bradlaugh’s more militant approach. This became apparent in 1876, when Foote was expelled from the National Secular Society (NSS), of which Bradlaugh was the president, and in 1877, when he became one of Bradlaugh’s most vocal critics over the latter’s support for the republication of The Fruits of Philosophy, a birth control pamphlet.

All was to change in 1881, when Bradlaugh was prevented from taking his rightful place in the House of Commons. Up until then Foote had favoured a quiet scholarly life, but Bradlaugh’s treatment enraged him. Foote rejoined the NSS and in May issued the first number of his new newspaper, The Freethinker. He set out his stall in the first issue:

‘The Freethinker is an anti-Christian organ, and must therefore be chiefly aggressive. It will wage relentless war against Superstition in general, and against Christian Superstition in particular.’

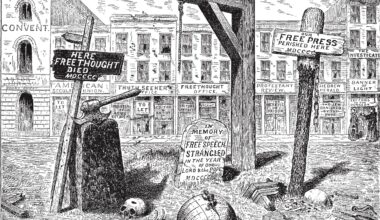

Foote was as good as his word; his primary weapons were parody and satire. From an early stage he introduced a weekly ‘Bible cartoon’, which was particularly hard-hitting and incensed the religious – it always seems to be satirical cartoons that enrage such people the most. Foote’s writings to challenge the widespread assumption that religious views should be treated with reverence; he sought to establish that religion is a social phenomenon that should be open to the same range of comment as any other aspect of life. Such tactics seemed popular with some: after just four issues, the Freethinker changed from being a monthly to a weekly publication.

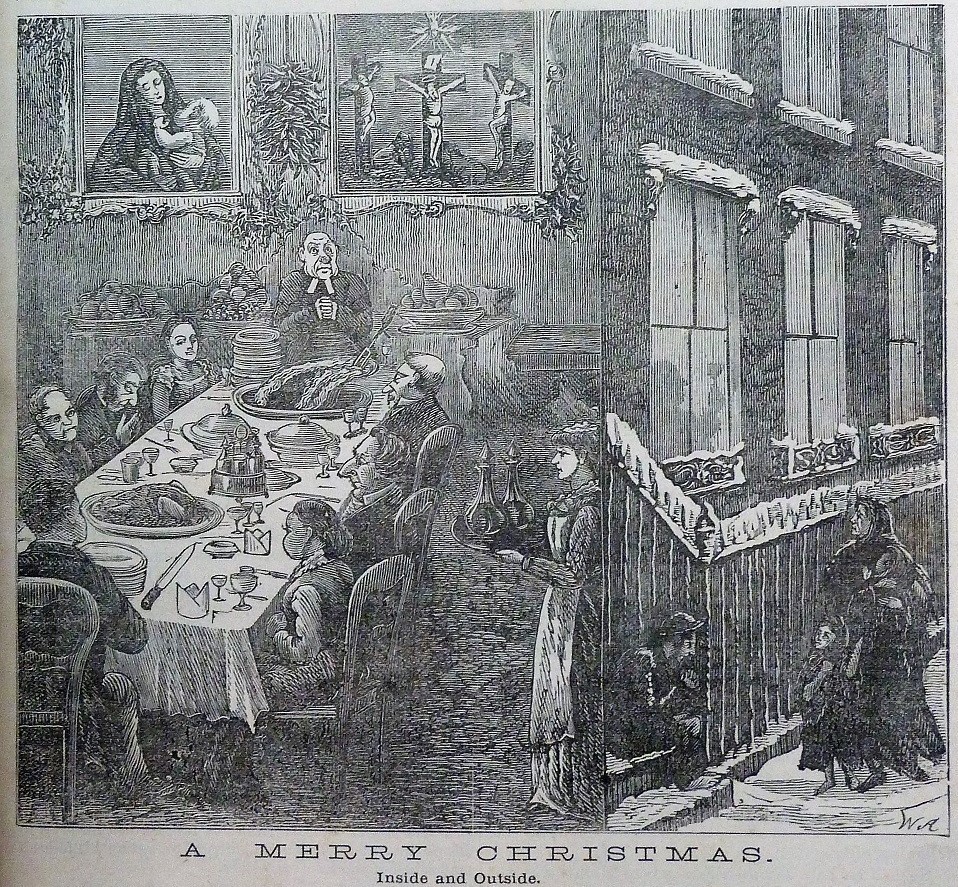

Foote had no doubt that his journal was inviting trouble, but continued to provoke. On 26 February 1882 he wrote, ‘we are accused of blasphemy, and we shall continue to justify the charge.’ At the same time, he noted an increase in sales, and seemed to regret that no charges had yet been brought. All was to change on 16 July, with Foote’s announcement, ‘we are in for it at last’, and the addition to the masthead of a banner that read ‘PROSECUTED FOR BLASPHEMY’. Two blasphemy prosecutions were brought against the issues of 28 May 1882, in which a cartoon of ‘Divine Illumination’ had proved particularly controversial. The second prosecution indicted the Christmas Number of 1882. This contained a cartoon entitled ‘A Merry Christmas, Inside and Outside’, with a cleric’s table laden with food inside and a ragged, poor family outside. There was also the infamous cartoon of ‘Moses Getting a Back View’, and a strip cartoon entitled ‘The Life of Jesus’.

The second prosecution came to trial first, in March 1883. Foote, as editor, was accompanied in the dock by William J. Ramsey, the shop manager, and William Kemp, the printer. They appeared before Lord Justice Sir Ford North, a devout Catholic whose attitude towards the defendants was hostile throughout. Despite the Judge’s advice to the jury, they failed to convict and a retrial was ordered for the following week.

The second trial was again held before North, and concluded with Foote’s stirring defence of free speech, but to no avail. North’s summing up was unremittingly hostile, and this time the jury convicted. Foote was sentenced to twelve months in prison, Ramsey to nine and Kemp to three. The severity of the sentence came as a shock even to Foote’s opponents. His response has become famous: ‘My Lord, I thank you, it is worthy of your creed.’ Foote had achieved a certain sort of martyrdom.

Foote and Ramsey were back in court for a third trial in April, on the charge relating to the Freethinker issue of 28 May 1882. This time the case was heard by Lord Justice Coleridge, who, in contrast to North, treated the defendants with consideration and courtesy. The jury failed to reach a decision and although a retrial was expected, this never occurred, the prosecution mysteriously dropping the case. They would, presumably, have been aware of the Freethinker’s burgeoning sales, as well as the hostile comments from many sections of the Press and society at what was widely seen as overly harsh treatment of the defendants.

Throughout the trials, Foote conducted his own defence. One of the main planks of his case was that his crime had been to peddle blasphemy cheaply to working people, while polite agnostics and sceptics were left to carry on undisturbed. He incorporated descriptions of technically blasphemous material written by respectable figures of the time, including members of both Houses of Parliament and some of the greatest names in English literature. A similar argument had been used by Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant some ten years earlier when they had been prosecuted for selling cheap birth control advice, while expensive, ‘respectable’, medical publications provided the same information. If the case raised the issue of free speech in general, it also raised the question of whether that right extended to all or only some sections of society.

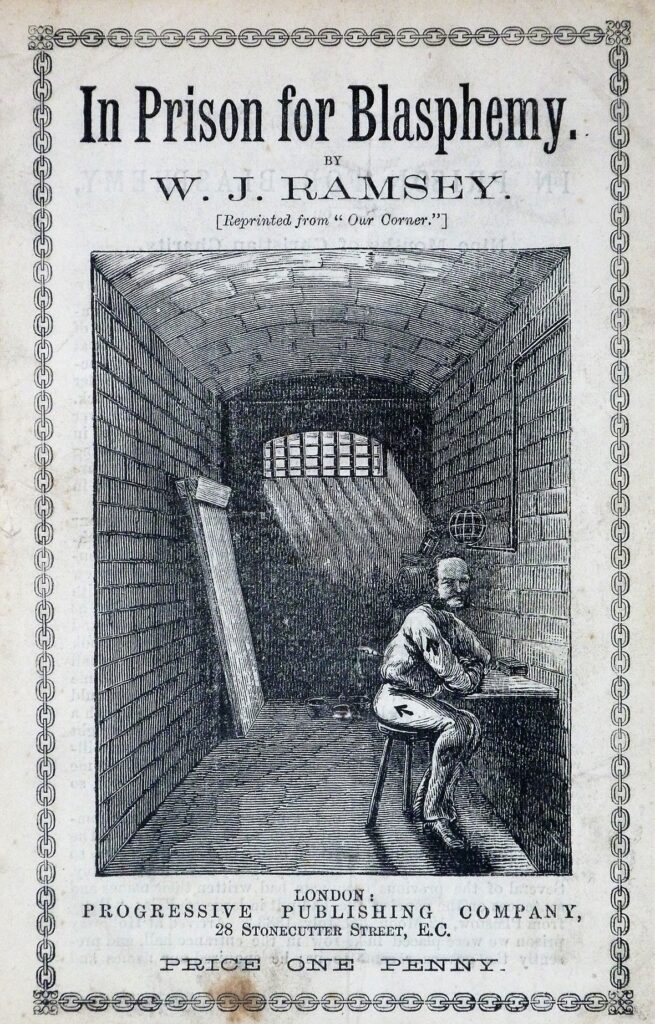

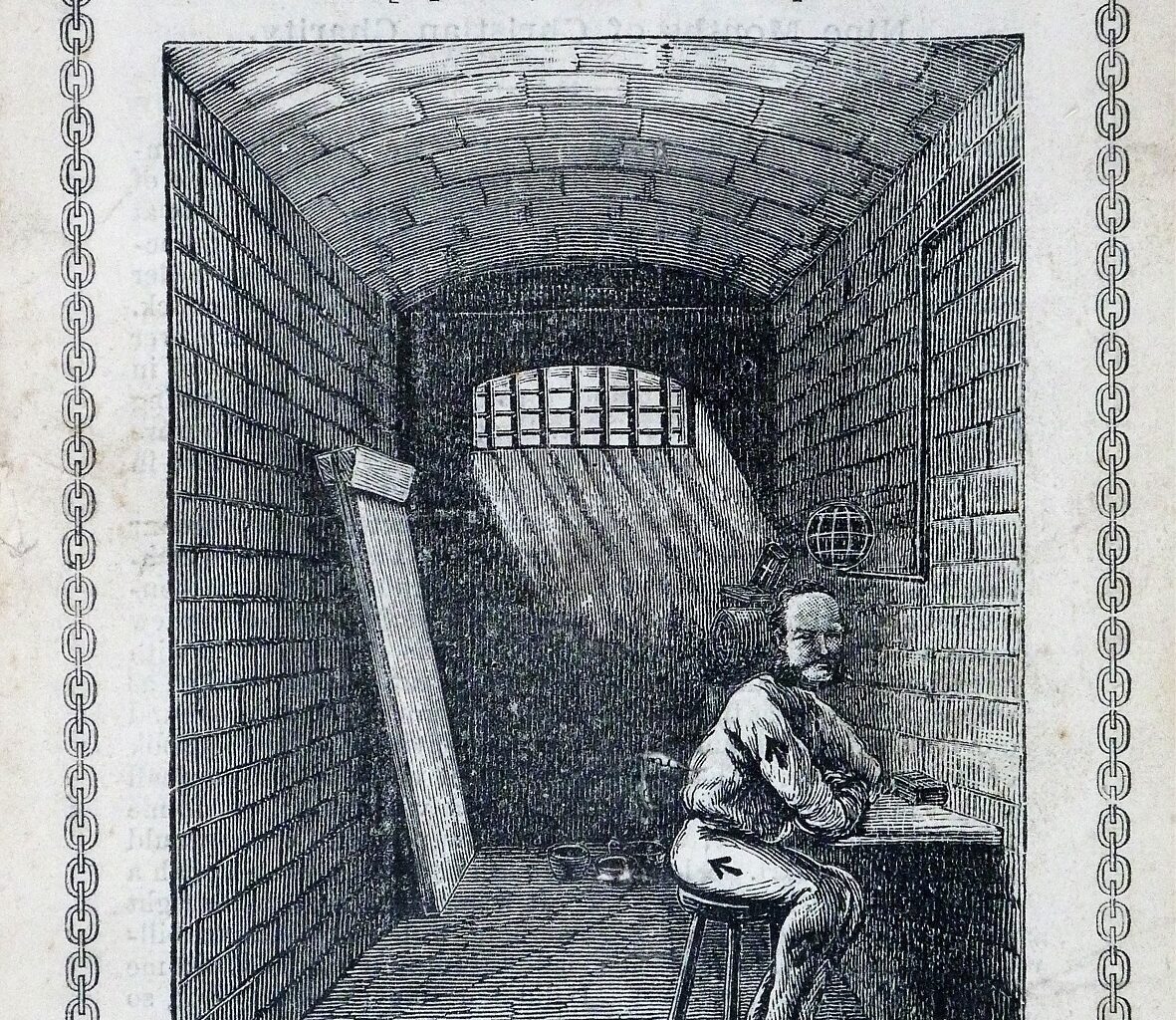

Foote, Ramsey and Kemp served their sentences at Holloway under the severe regime of a Victorian gaol. Meanwhile, the Freethinker continued to be published under the temporary editorship of Edward Aveling, although the cartoons ceased pending Foote’s release. Foote was to record his experiences both in the columns of the Freethinker and in his book Prisoner for Blasphemy; the latter deals with his trials and imprisonment in graphic terms and is a valuable description of prison conditions of the time. Ramsey produced his own brief account, with a title page adorned with a sketch of the author in his prison cell.

Foote was released early on 25 February 1884. The account in the Freethinker estimated that a crowd of some 3,000 greeted him as he emerged. There was a procession of carriages across London and a breakfast at the Old Street Hall of Science, followed by a banquet and various packed public meetings. Foote resumed editorship of the magazine, the cartoons reappeared and he personally delivered the first copy off the press to Ford North.

The episode was significant in a number of respects. In his ruling, Coleridge determined that only matter intended to shock, insult, or outrage believers was prosecutable as blasphemous, thereby narrowing the grounds on which blasphemy charges could be brought. The mere statement that a person did not believe in God was no longer indictable. This did not mean that blasphemy prosecutions ceased, although neither the Freethinker or Foote were prosecuted again. The centrality of the journal and its editor to the secularist cause was confirmed, and when an ailing Charles Bradlaugh resigned his Presidency of the National Secular Society in 1890, Foote was his obvious successor. More generally, the issues of freedom of speech, religious entitlement and inconsistences in the way less privileged members of society were treated by the law had been opened to scrutiny and debate for those with eyes to see.

1 comment

Testing comments.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate