June is Blasphemy Month at the Freethinker. This article contains a detailed account of the trial of Mubarak Bala, the President of the Humanist Association of Nigeria, for blasphemy in Kano State in Nigeria’s Muslim north. It is based on interviews with the head of his legal team, James Ibor, and fellow humanist, Leo Igwe, as well as on publicly available court documents. The article sets out Bala’s allegedly blasphemous statements, and describes his prison conditions and the threats to his security from within prison. It also includes a comment by Andrew Copson, President of Humanists International, an organisation which has supported Bala since his arrest in April 2020. For comparison, we then reflect on the case of Deborah Samuel, a Christian who was killed by a mob for blasphemy in May in the nearby state of Sokoto.

The Freethinker reported in March on the humanist Mubarak Bala’s impending trial for blasphemy in Kano, northern Nigeria. His bail application was rejected by the Kano High Court on 4th April. On 5th April, he suddenly, and without previously notifying his legal team, changed his plea to guilty. The judge then sentenced him to 24 years’ imprisonment. This sentence, in the view of James Ibor, the head of Bala’s legal team, is probably unlawful, and the case is being appealed. In the meantime, Bala remains in custody in Kano State Prison.

The High Court of Abuja had granted a previous bail application back in December 2020, but its order for Bala’s immediate release had simply been ignored in Kano. At the bail hearing in Kano, his team ‘argued for bail extensively,’ Ibor told me via Zoom. ‘But unfortunately the court denied it on the ground that he would not be safe if he was released.’

This explanation, in Ibor’s view, was disingenuous. ‘They were using his incarceration as a total tool to compel him. The inmates actually told him while he was in custody that the court would not grant him bail – and that’s what happened.’ Leo Igwe, a co-founder of the Humanist Association and leader of the campaign to free Bala, agrees. Had the authorities really been concerned for Bala’s safety, he argues, ‘they shouldn’t have transferred him to Kano [from Kaduna] in the first place, where he wasn’t living and where even the so-called offence didn’t happen.’

The bail hearing took place on a Monday, and the trial on Tuesday. The previous Friday, just before Ibor himself arrived in Kano, the prosecution filed two amendments to the charge sheet, increasing the number of charges from ten to 17. Immediately after the bail application had been refused, they filed yet another amendment to increase the number to 18. ‘Strategically, we chose not to object,’ says Ibor, ‘because they were all of them full of repetitions and grossly defective.’ Instead, they decided to proceed to trial, in order to avoid any further prevaricating by the other side.

It came as a shock to Ibor when Bala suddenly changed his plea to guilty on the morning of the trial: ‘I was frustrated and confused.’ He managed to persuade the court to stand down for 15 minutes while he consulted his client privately. Bala then explained that he had ‘lost faith in the judge and the justice system in Kano’, and was worried that if he won his case, he would be killed.

Ibor argued that the press were there, and members of the international community (the US in particular had sent trial observers). The judge, he told Bala at the time, might ‘caution himself and try to do the right thing’. Bala seemed to be persuaded to change his plea back to not guilty. ‘But unfortunately, when we got back to court, he again repeated that he was guilty,’ says Ibor, ‘So at that point, there was nothing I could do.’ According to Ibor, Bala later explained that he wanted his legal team to be safe as much as himself: ‘There would likely have been riots if he had been acquitted.’ As Igwe puts it, ‘he said that there was no way they could have won in Kano and remained alive.’ It is abundantly clear that Bala’s change to a guilty plea was a matter of expediency only, necessitated by the fear of violent reprisals. ‘There is nothing to apologise for, absolutely nothing,’ says Igwe.

Ibor argues that the sentence imposed on Bala was ‘unknown to law’. According to him, the maximum sentence should have been five years, under the two provisions Bala was charged with, sections 210 (‘insult to a particular religion’) and 114 (‘acts calculated to cause a breach of public peace’) of the Kano Penal Code.

For the record, the Freethinker is now able to publish the key posts on Bala’s Facebook page in April 2020 on which the prosecution relied, as quoted on the charge sheet (a public document):

1. ‘There’s no difference between the prophet TB Joshua (S.A.W) of Lagos State and Muhammadu (A.S) of Saudiyya. The one in Nigeria is better because he is not a terrorist.’

[T.B. Joshua was a Nigerian pastor and televangelist. ‘S.A.W.’, conventionally used of Mohammed, means ‘peace and blessings of Allah be upon him’; ‘A.S.’, meaning ‘peace be upon him,’ is conventionally used of lesser prophets. Bala seems to have reversed the two. This statement, in Hausa, was posted on 25th April 2020 – three days before his arrest.]

2. ‘Islamic religion is kafirci against the original Kano religion of Tsumburbura mai Sawaba, (the goddess that was worshiped at sometime). May Alliya (the goddess) guide Kano people.’[‘Kafirci’ means ‘unbelief or a state of non-belief’; ‘describing Islam as kafirci delegitimises it,’ according to Igwe. This statement was originally in Hausa.]

3. ‘Muslims are about to start fasting to the God that refused to eradicate their poverty despite the fact that they prayed 17 times everyday. How i wish Allah exist.’ [Originally in Hausa.]

4. ‘There are no flying horses, there is no Allah, Islam is exactly as Boko Haram practices it. Whoever believes religion has been duped.’ [Originally in English.]

5. ‘If you can’t take the blasphemy against Islam, criticizism (sic) of its doctrines, this page is not for you. I have not even started ooo’ [Originally in English.]

According to the transcript of the trial (a public document), the judge, in his ruling, stated that [sic]:

‘No one stops him [Bala] from any religion, but he should understand that where his intent stops, the intent of another person start, therefore the intent that he is thinking that he has to say whatever he wants to say or put anything is not absolute. He should be careful. There are a lot of people that may have the same ideology but not expose themselves like that.

‘He should go and believe in his own faith and allow others to believe in their own faith. There is no compulsion in religion not to take of insulting any particular religion for that matter.

‘I hope his stay in correctional center would sure serve him a great lesson and others.’

Under Nigerian law, a defendant who pleads guilty should usually receive a reduction in sentence. But that did not happen, says Ibor. ‘The judge told me that I was lucky that he had not imposed a death sentence’ – even though this would have been unlawful, as Bala was being tried under customary (secular) and not sharia law, as he was not a Muslim.

Igwe argues that the length of the sentence is ‘unprecedented’ for these offences. ‘But it is all part of the calculated attempt to make sure that this guy is shut out, he’s behind bars, and that a message of oppression is sent to people like him.’

It was particularly difficult for Bala to be in prison during Ramadan. According to Ibor, there were ‘about 1700 inmates, all of them Muslims, fasting. He’s the only one who eats, and they constantly remind him that he’s an unbeliever and he deserves to die.’ He has also experienced threats, as well as ‘bullying from the very day he was admitted into the facility.’

Bala has maintained his humanist convictions. But he has faced immense pressure, even in matters as personal as trying to give his wife, Amina Ahmed, a hug when she came to visit. For strict Muslims, public displays of affection are not allowed, even between couples. When the pair stood up to hug, the inmates ‘shouted down at them and warned him never to try it,’ says Ibor, ‘Why should he hug? He said, “it’s my wife,” they said, “how dare you?”’ Amina now faces the prospect of continuing to bring up their son, Sodangi, alone, possibly for the whole of his childhood. ‘I think she was devastated by the judgment,’ says Igwe. ‘But she’s finding a way to cope with this, what has been a very difficult situation for her and the baby and the entire family.’

Prison conditions have been tough in other ways too. Bala has had access to writing materials, and communicated regularly with Ibor and others. But some of his letters never arrived, or were censored. He has shared a cell with up to nine other inmates. Sometimes, says Ibor, it has been ‘a very tiny cell where it’s even difficult for him to move around or adjust. He has had to stay in a particular position for a long time because there are so many people in it.’ As for the food, ‘it is really horrible.’

‘His rights have been so clearly violated in so many different ways,’ says Andrew Copson, president of Humanists International, which has supported Bala and his family since he was first detained in April 2020. ‘Every aspect of his case is a disgrace’ – from the denial of access to justice, to the displacement from Kaduna, where he was arrested, to Kano, to the ‘overblown’ charges.

On 12th May, just over a month after Bala’s trial, Deborah Samuel, a Home Economics student and Christian in Sokoto State, also in Nigeria’s Muslim north, was beaten to death and set alight by Muslim fellow students who accused her of blasphemy. According to Reuters via the Guardian, a student posted an ‘Islamic’ message on her department’s WhatsApp group. In response, she posted an audio recording that protested against the use of the group for religious broadcasting, and allegedly contained ‘blasphemous comments on the prophet of Islam’. The Peoples Gazette, an Abuja-based paper, shared a chilling video of a man apparently confessing to Samuel’s murder and showing a matchbox which he appears to say he had ‘used in setting her ablaze’. When two suspects were arrested, a mob of ‘Muslim youths’ rampaged through the city ‘lighting bonfires’ and demanding their release.

The suspects are currently awaiting trial; a large group of Muslim lawyers appeared in court to support them in their first appearance in court. However, they have not been charged with murder, but with the lesser offences of ‘criminal conspiracy and inciting public disturbance’. This has been criticised by the Nigerian Bar Association, which called on the Sokoto State Government to bring ‘charges that truly reflect the gravity of the situation’; the Senior Advocate of Nigeria, Ebun-Olu Adegboruwa, described them as ‘watery charges’.

There is a disquieting contrast between the harsh treatment of Mubarak Bala, held in custody without trial for nearly two years and now sentenced to twenty-four, and the lenient treatment of Deborah Samuel’s alleged killers. This difference reveals how far fundamentalist Islam is entrenched in the culture of northern Nigeria, and underlines its proponents’ utter disregard for human dignity or rights. It has been argued that Samuel’s case is part of a trend of Islamist persecution of Christians in both the north and the south. However, as Bala’s case demonstrates, the persecution is not confined to Christianity, but extends to anyone who dares to criticise Islam or resist its influence.

To some extent, the problem of illegitimate influence on the judiciary is one that affects the whole country. ‘I want to be very frank with you,’ says Ibor, ‘Nigeria has no respect for the fundamental rights of citizens. What plays here is usually politics and religion, and religion itself is politics. The judiciary of Nigeria is not independent.’

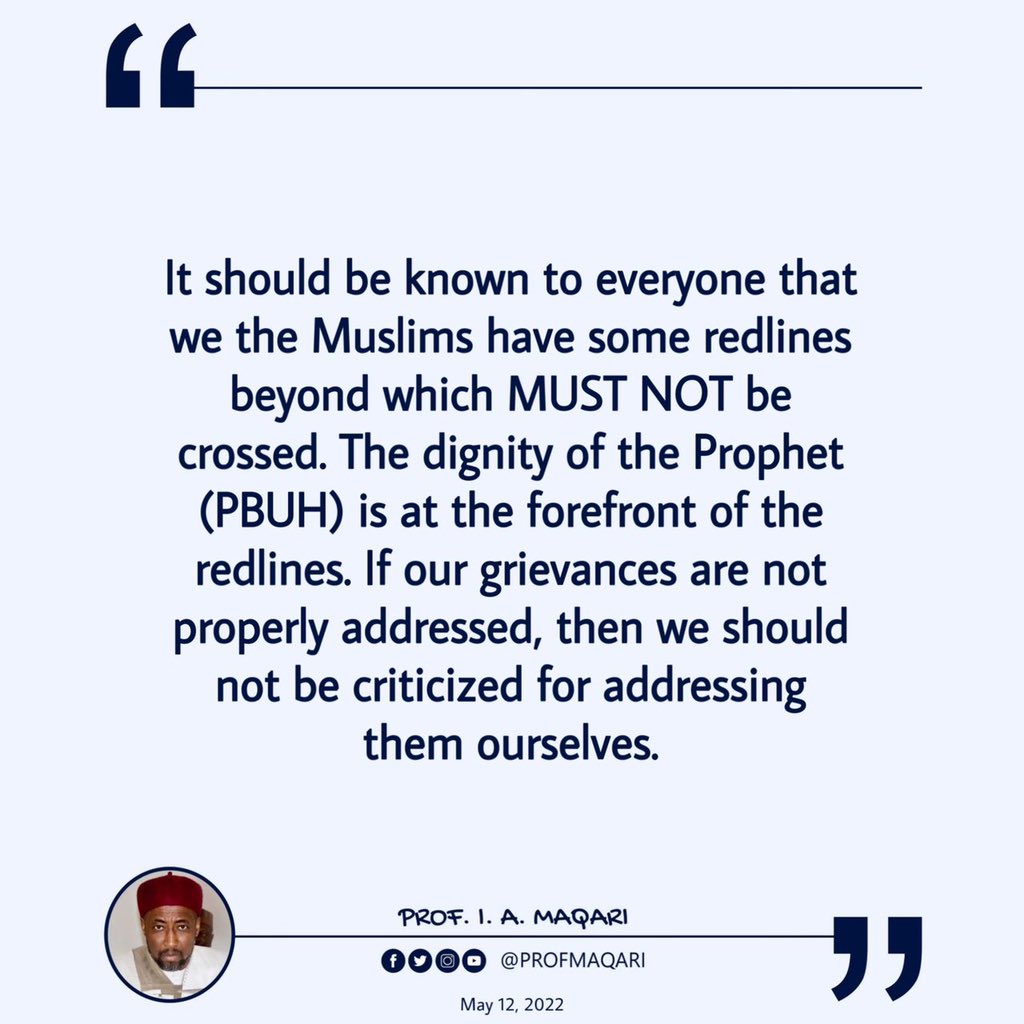

Yet the idea that blasphemy against Islam in particular is a crime that merits death – which it is not under the secular Nigerian constitution but only, at most, under sharia law – is shared by high-ranking clerics. In an interview with the Nigerian newspaper The Punch, Professor Ibrahim Maqari, the imam of the National Mosque of Abuja, said that ‘she [Deborah Samuel] deserves death, there is no doubt about it … Nobody can insult the prophet the way the girl did and think they can go untouched.’ Although Maqari argued that it should be the state authorities who carried out such punishments, he also said that ‘extrajudicial killings’ were ‘something that we cannot stop so far the government does not fulfill its responsibilities.’ In other words, the authorities have a ‘responsibility’ to execute blasphemers; if not, do not be surprised if someone else does it for them.

In cases like Bala’s, Ibor stresses the role that the international community can play: ‘They have a lot of influence on Nigeria.’ Andrew Copson is one of those who have been involved, on behalf of Humanists International, in lobbying the UK government. Along with the US, Norway, and others, the UK has raised Bala’s situation with the Nigerian government through diplomatic channels. While the US has led the efforts, Copson stresses the ‘impressive communal effort that has been exerted on Mubarak’s behalf.’

Yet diplomatic pressure is probably only a short-term solution. After all, Western governments and NGOs may be able to help individuals like Bala, but it is difficult to see how much influence they can exert over a country of 216 million people speaking around 500 languages, and one in which Christian, Muslim and local religious traditions are deeply engrained.

On the other hand, it is people like Bala who have been starting, very slowly, to open people’s minds and change the culture from within, by holding meetings in person or online, campaigning through groups like the Humanist Association of Nigeria or the Atheist Society of Nigeria, and above all, criticising religion, at great personal risk. That is why his ongoing detention is such a blow for freedom of conscience and expression in northern Nigeria: the incipient humanist movement has lost its leader. Bala’s treatment demonstrates how firm a grip the religious authorities, backed by the threat of mob violence, continue to have over the justice system and public opinion.

The conclusion is that future progress in this region is likely to come only through a long and painful process of attrition. In the meantime, an innocent student has been brutally murdered, a man faces decades in prison for criticising an idea, and Sodangi is growing up without a father. In countries where Islam has political power, the price of dissent is high indeed.

Enjoy this article? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on freethought.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate