Ask people, at least in the UK, who Thomas Paine was, and you will often meet with an embarrassed silence. Which is astonishing, given that his pamphlet Common Sense (1776) galvanised the American War of Independence, his book The Rights of Man (1791) pioneered the idea of republican freedom and democratic justice – driving Pitt’s government into a frenzy of censorship and prosecution – and his writings about religion emphasised the importance of freedom from orthodoxy. Born in Britain, Paine participated in both the American and French Revolutions. He was a man who really did change the world and helped to forge the modern era. His ability to do this was due not least to his bold freethinking stance.

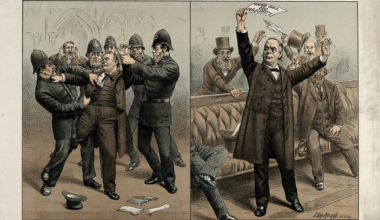

Common Sense became America’s bestselling book, but Paine refused to exploit its success financially. He was hailed by some as a hero of progress and freedom, while the reactionary press of his era devoted itself to attacking him, prompting state-sponsored burnings of his effigy up and down England.

Lincoln privately admitted that he never tired of reading him. Edison and Bertrand Russell sang his praises, as did G. W. Foote: ‘The keenness of his intellect was matched by the brilliancy of his imagination. He stated truth in a way that men could see, hear, and feel it. His name stands for mental freedom and moral courage.’

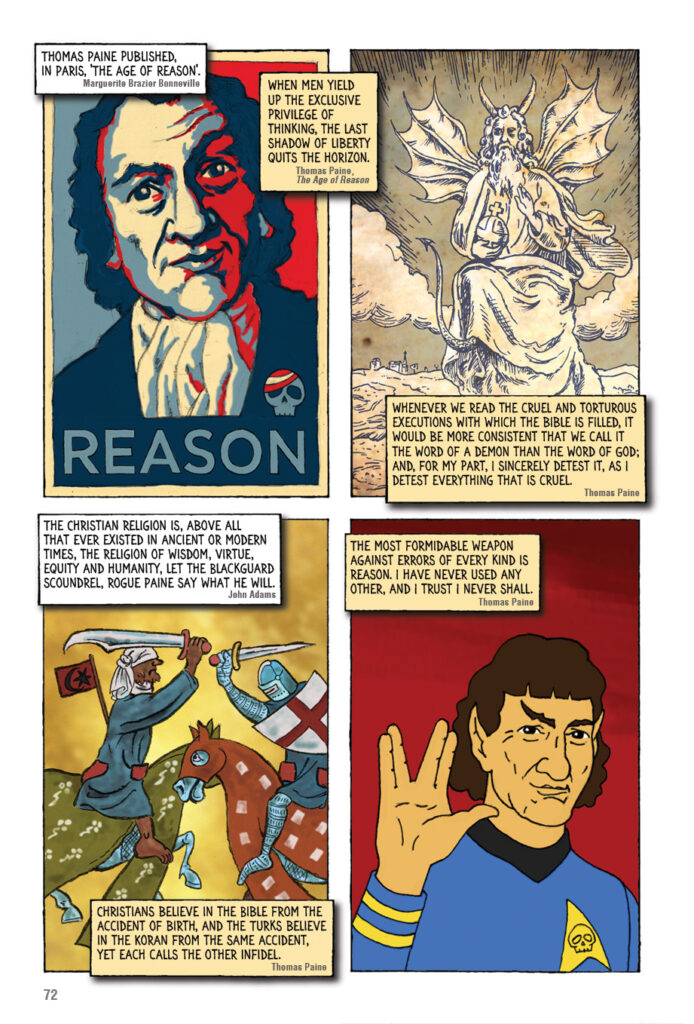

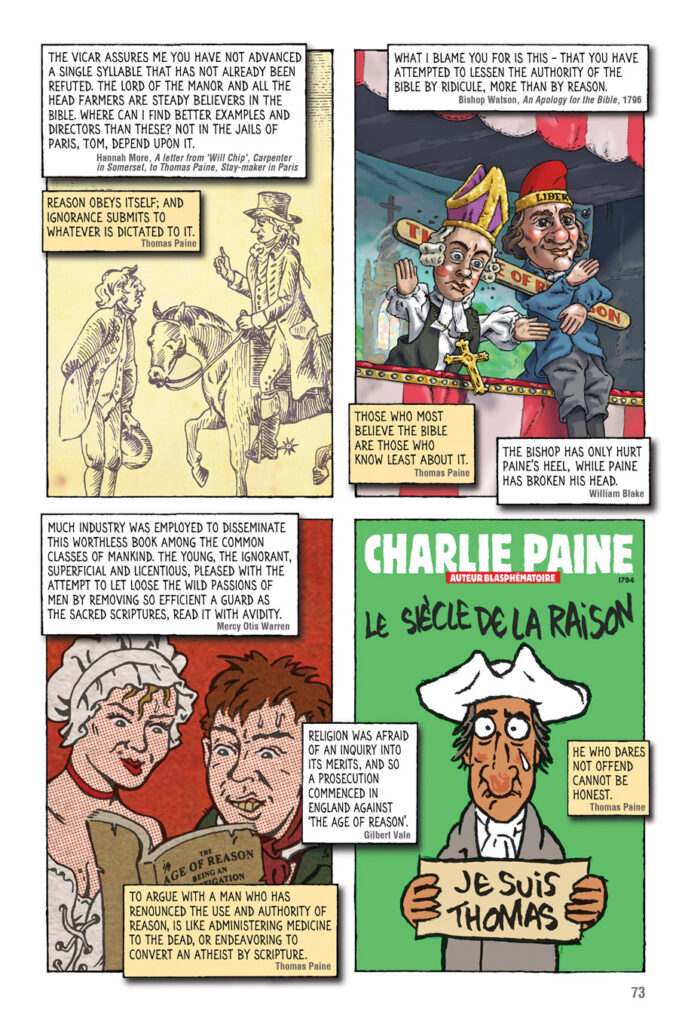

Yet despite the interest of Paine’s story and the influence of his ideas, he is little known these days outside academic circles. I think this is partly due to The Age of Reason, parts I and II of which were written in France in the early 1790s, at the height of the Revolution. This book cost him his reputation at the time it was published. He boldly argued that ‘revealed’ religions, in which a human prophet claims to pass on the unchallengeable messages of God to their fellow human beings, cannot be taken literally or seriously, and are therefore irrational. His independent spirit is shown in assertions like the following:

‘I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.’

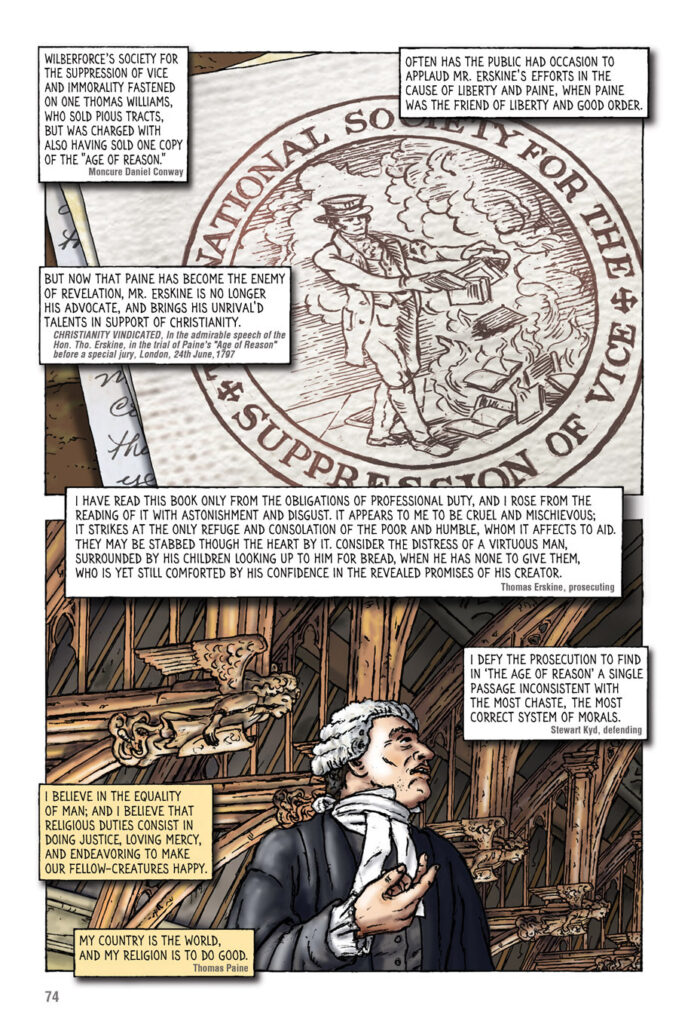

Unfortunately, even for the radicals of his era, forsaking Christian orthodoxy was a step too far. Paine was shunned, abandoned and even condemned by all but a few of his ‘respectable’ friends and allies on both sides of the Atlantic. The press vilified him as drunken, immoral, filthy and dangerous.

Paine’s ideas about religion meant that, to a large extent, it was atheists and secularists who kept his memory alive. This is ironic, since he was a deeply religious man, a deist who believed the only true testament of God was the sublime creation that everyone can directly witness. As such, he actively opposed atheism.

I was inspired to write Paine: A Fantastical Visual Biography biography, in the form of a graphic novel, as a way of paying homage to the world’s least known revolutionary freethinking hero, and hopefully rescuing him from oblivion. I’m grateful to all those who crowdfunded this project and made it possible. Below is a three-page extract.

Paine: A Fantastical Visual Biography (2022), £12.00, pp 112, self-published by Polyp (a.k.a. Paul Fitzgerald) can be purchased here.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate