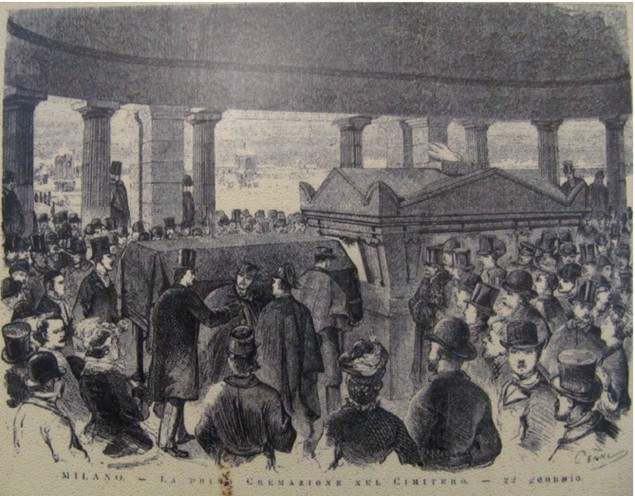

In January 1876, an unprecedented event took place at Milan’s Cimitero Maggiore: Europe’s first modern crematory was put into operation. Within 90 minutes, the new incinerator for human corpses, invented by engineer Celeste Clericetti and professor of chemistry Giovanni Polli, transformed the mortal remains of silk merchant Alberto Keller into ashes. It was the very same Keller who had sponsored the construction of this crematory and who, embalmed and provisionally kept in the non-Catholic part of the cemetery, was the first to be officially cremated in Italy two years after his death.

The cremation was attended by friends and family, state officials, and members of the Milan Cremation Society (established in 1876 thanks to the tireless commitment of physician and freemason Gaetano Pini) as well as scientists, engineers and media representatives. A perhaps unexpected guest was the Protestant pastor Paira, who framed Keller’s funeral with words that stretched the principles of Christian teachings rather far. Paira declared that Christian religion should finally embrace humanism, progress, modernity and hygiene, and abandon what he perceived to be a superstitious tradition centred on a lifeless shell and a vulgar belief in bodily resurrection.

At first glance, the renewed interest in cremation in nineteenth-century Italy may be surprising, as this mode of treating the corpse did not conform to the Catholic burial traditions that had dominated the cultures of the Italian peninsula for most of its history after the rise of Christianity. But this is precisely why, during the Italian process of nation-building, those, like Giuseppe Garibaldi or the aforementioned Pini, who wished to create a civil public sphere free of religious influence, chose cremation as one of their means to oppose Catholicism, which was politically and culturally so influential. Cremation was a way of rejecting Catholic traditions, institutions and experts, which seemed altogether incompatible with the reformers’ visions of science-based progress, reason, rationality, civil morality and a bright Italian future in the European concert of nations. In the second half of the century, the idea of incinerating the dead in Italy became inseparably linked to a culture war between the Catholic Church and an emerging Italian secularist sphere. The latter was partly fostered by the secularisation policies of the liberal state.

Founded in 1861, the young nation-state of Italy actively upheld French revolutionary political traditions. Cremation, which had been introduced briefly during the revolution as an explicitly non-Catholic custom, formed part of this heritage. However, the cremation of the dead was not in itself a ‘secularist’ practice. Rather, it became charged with secularist significance. On the one hand, Italian secularists promoted cremation, considering it antithetical to Christian traditions. On the other hand, the Church’s dogmatisation and anti-modernisation policies in the second half of the nineteenth century included the condemnation of cremation in 1886, which came to be devalued as a Masonic ritual. Eventually, cremation was legalised, and therefore implicitly supported, by the Italian Sanitary Code in 1888.

A closer look sheds light on these competing parties in the Italian confessional-political conflicts of the later nineteenth century. On the one hand, Italian politics was dominated by the Historical Right (Destra Storica) with its liberal, reformist and secular orientation. Politicians such as Massimo d’Azeglio or Camillo Benso, Conte di Cavour, represented this direction. Close to these positions, though less pragmatic and even more oriented towards ‘modernising’ the new state, was the democratic and urban-based Historical Left (Sinistra Storica) with leading figures such as Urbano Rattazzi and Agostino Depretis. Both parties shaped the outlook of the new state. Members of the Historical Left tended to be less tolerant of religion, its institutions, and its influence in society, and here they joined with the efforts of secularist organisations and campaigners. Among them were Italian freemasons like Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazzini, both of whom worked at the forefront of the national cause, as well as freethinkers like Luigi Stefanoni, who edited the influential journal Libero Pensiero (‘Free Thought’), atheists, anarchists and early socialists.

Even though secularism in Italy was heterogeneous and also competitive in its branches, nevertheless, anti-Catholic and anti-clerical secularist publications and organisations openly and unanimously advocated cremation and civil burial to challenge the Church’s prerogative over the dead. But they also offered secularist explanations regarding life and death. Such thinking was inspired by the ideas of the anti-clericalist and scientific materialist Jacob Moleschott on the cycles of ever-changing matter.

Rome only joined the new nation state in 1870, after the city had been captured by Italian troops. This marked the end of the popes’ temporal power. Even before that, the influence of the Church in society had already been reduced by the Italian Civil Code of 1865, as well as by legislative initiatives such as those of Giuseppe Siccardi, which abolished ecclesiastical courts. As a result of its loss of territory and power, the Church reacted harshly to the new state and the secularisation that accompanied it. Its particular bugbear was the radical secularists, with their campaign for cremation, their demands for the emancipation of women, for civil morality, and for an education free of religious influences. Cremation remained forbidden for Catholics until 1963. The leading Catholic journal Civiltà Cattolica spearheaded the polemics against the new practice, which it attacked as ‘a war against the dead’.

Numerous cremation societies were founded in Italy in the nineteenth century, united in an umbrella association led by Malachia de Cristoforis, a senator, professor of medicine and freemason. Crematoria were built in several Italian cities; by 1894 they existed in Milan, Lodi, Cremona, Rome, Brescia, Padua, Udine, Varese, Novara, Florence, Livorno, Pisa, Como, Asti, St. Remo, Turin, Mantua, Verona, Bologna, Modena, Venice, and Perugia. However, few Italians were willing to opt for cremation, given how charged this new way of treating the corpse was. While numbers have risen nowadays, cremation remains a minority practice in Italy whose population continues to be predominantly Catholic (around 75 per cent), followed by agnostics and atheists (approximately 12 per cent), various other Christian denominations, Islam and Buddhism. In 2019, only about 31 per cent of the deceased were cremated; inhumation predominates.

In 1878, two years after the first modern crematory was built in Milan, the second was constructed in Gotha, one of the capitals of the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. In this city, liberal and socialist ideas flourished. The German socialist party (the SPD), for instance, came into being here in 1875. Cremation was advocated by leading German freethinkers such as Ludwig Büchner, well-known monists like Wilhelm Ostwald, and the prominent socialist and later anarchist Johann Most.

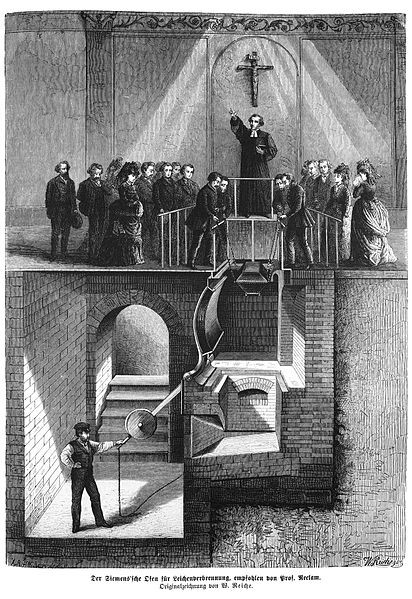

Just as in Italy, the new way of dealing with the dead was accompanied by strong anti-clerical and anti-Catholic ideas in Wilhelmine Germany as well, for example by the professor of medicine Karl Reclam in the widely read bourgeois family magazine Die Gartenlaube (1874, 1879). In Protestant Germany, however, the issue of cremation seemed less politically charged. In Catholic-influenced cultures, the practice faced brusque rejection from the church. In Protestant Germany, on the other hand, after initial outright disapproval in 1898 (at the Conference of Eisenach), the Protestant churches, in practice, often adopted a more conciliatory approach. Comparatively early on, German Protestants could opt for cremation. In doing so, they affirmed their liberal and progressive convictions, or dispelled their fear of being buried alive, without giving up on a Christian ceremony. Of course, existing social norms favoured such Christian framing.

Scenarios such as those envisioned by Die Gartenlaube in 1874 were not possible in Protestant Prussia, where throne and altar were closely linked at the time and where, unlike in Italy, state law did not permit cremation until 1911. Nevertheless, the boundaries between secularism and liberal Protestantism in Germany and elsewhere eventually proved less solid than in Catholic cultures. Even so, cremation in the nineteenth century would still have carried an aura of the sensational, the deviant, even in Protestant regions, and would have indicated a turning away from the established religions and beliefs of those who opted for this practice.

After the turn of the century, with the rise of the German labour movement, cremation in Germany took on more socialist features. This was also due to special cremation insurance policies that were set up for workers and their families to provide them with financial security in the event of death. Prominent socialists such as Friedrich Engels and August Bebel chose to be cremated. In a sense, socialist culture disambiguated and politicised the secular and secularist notions of cremation. Later on, this socialist codification of cremation led to high cremation rates in the socialist workers’ and peasants’ state of East Germany. Even today, the number of cremations in the former East German states is considerably higher than, for instance, in Catholic Bavaria.

The history of modern cremation ultimately turns out to be a winding road, laid by political revolutionaries, freethinkers, and freemasons, and paved with anti-clerical and materialist secularism, but also with bourgeois reformist, liberal Protestant attitudes: even in Italy, during the first cremation, a Protestant priest presided over the ceremony. Irreligion or agnosticism are to this day main reasons for choosing cremation; however, today, as in the past, cremation can also be selected for reasons of finance, flexibility and mobility, or on environmental grounds. Matters of belief and modern preferences and values are intertwined.

Today, cremation rates are rising across Europe, but the figures are distributed very unevenly, from countries where it is supported by a quarter of the population or less, such as Greece, Poland or Ireland, to those where it is supported by over 70 per cent, such as Germany, the UK or Sweden. New methods of dealing with the dead body now compete with cremation and burial. These include ‘terramation’, invented in the US, in which the corpse, in special composting chambers, is rapidly transformed into humus to serve as a nutrient for new plants.

Enjoy this article? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on freethought.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate