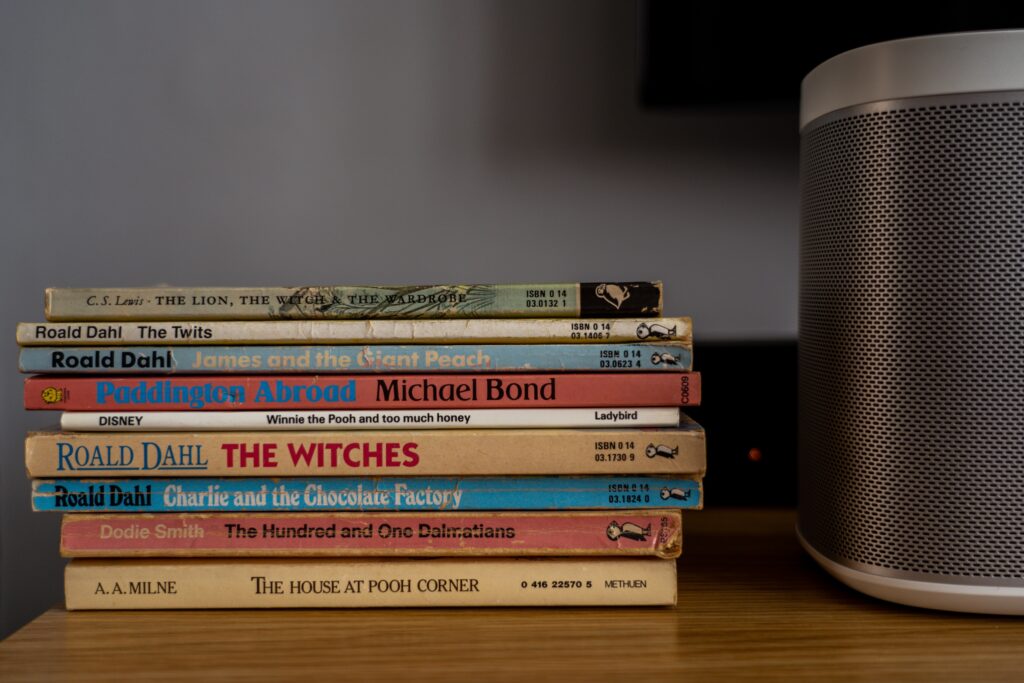

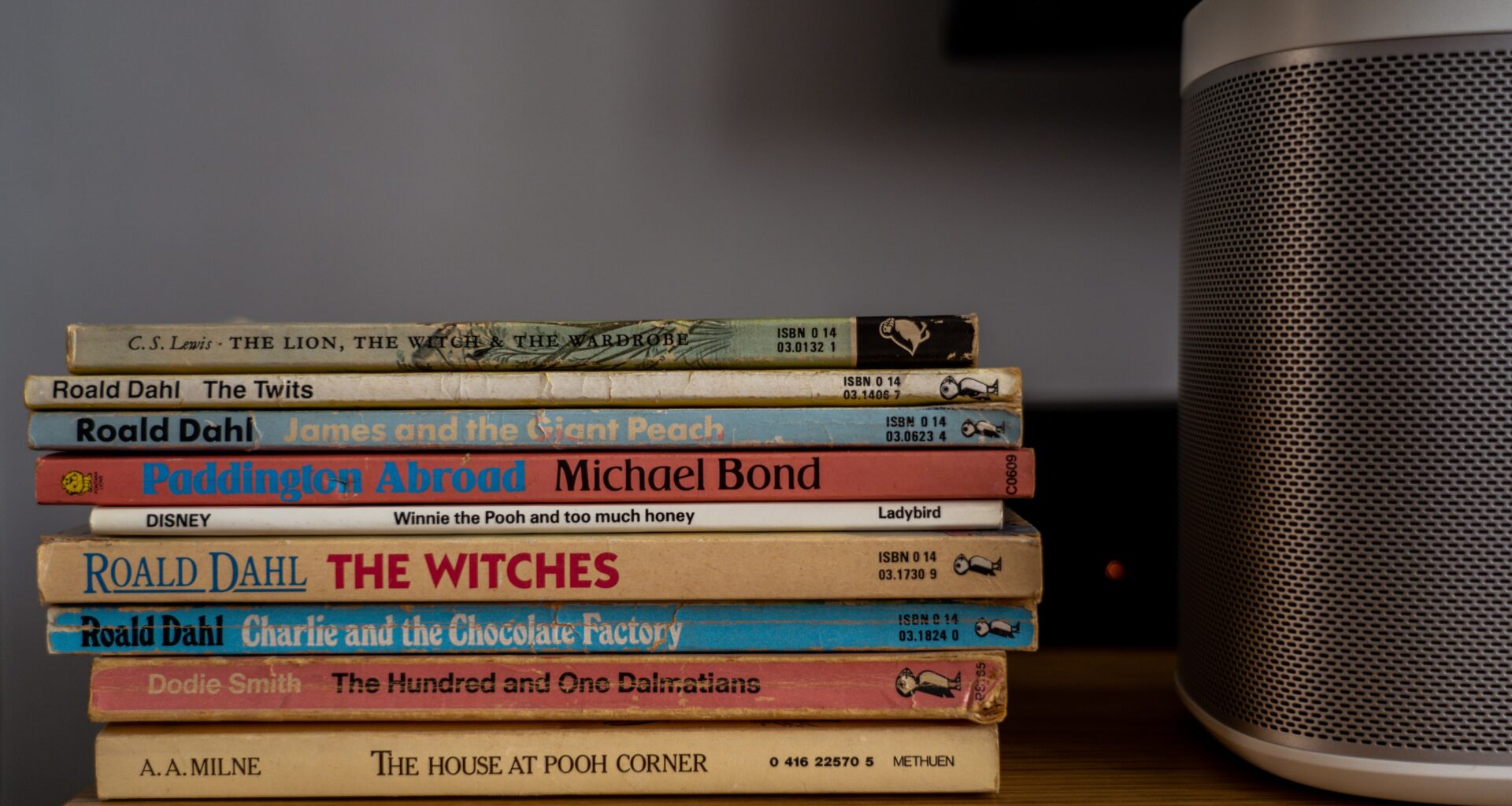

‘There’s more than one way to burn a book,’ wrote Ray Bradbury in Fahrenheit 451. The case of Roald Dahl, one of the best-known children’s authors of the twentieth century, having a number of his classic books rewritten, is a powerful example of just how true that is today.

The publisher hired a team to revise and remove all language they deemed offensive. This culminated in extensive alterations being made to some of the writer’s most famous books, as revealed in the report in the Telegraph which broke the story. Puffin brought in sensitivity readers to pore over Dahl’s words and make hundreds of changes to his work—in some cases, adding new passages to justify the author’s use of descriptive adjectives. For example, in The Witches, a paragraph explaining that witches are bald beneath their wigs now includes the line, ‘There are plenty of other reasons why women might wear wigs and there is certainly nothing wrong with that.’ In other cases, they are simply erased. The sentence, ‘There was something indecent about a bald woman,’ has been removed entirely. These are just two examples of the 59 edits made to just one of Dahl’s books.

For almost seventy years, Dahl’s stories have enchanted generations of children. The characters he created are some of the most memorable in all of children’s literature. This is partly because he employed a simple literary device: ‘good’ = ‘handsome’, ‘bad’ = ‘ugly’. In his surreal, bifurcated world, Dahl equates physical and moral beauty, evoking the darkly comic tradition of such literary heavyweights as Evelyn Waugh. As Dahl writes in The Twits, ‘A person who has good thoughts cannot ever be ugly.’ Part of the pleasure in reading his books was in picturing the many imaginative ways in which he described dispatching the villains. The feeling evoked in reading about their downfall was a kind of gleeful sadness. And Dahl always made sure the good guys were the final winners.

A majority of the edits have been made to Dahl’s descriptions of the characters’ physical appearance. The word ‘fat’ has been removed from every new edition. For example, Augustus Gloop in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is now ‘enormous’, and Aunt Sponge in James and the Giant Peach is ‘tremendously flabby’ when she used to be ‘terrifically fat’. Meanwhile in The Twits—my all-time favourite childhood story—Mrs. Twit is no longer ‘ugly and beastly’, she is just ‘beastly’.

Numerous references to gender are also gone. In The Witches, ‘chambermaid’ is now ‘cleaner’, while a woman’s likely profession is changed from ‘cashier’ to ‘top scientist’. It does not stop there. Any reference to race, indirect or otherwise, is gone. We now have a situation where a character turns ‘quite pale’ instead of ‘white’, while Mr. Twit’s monkeys no longer speak a ‘weird African language’, just an ‘African language’.

Dahl is no longer with us—he died in 1990. As such, he did not live to witness the impact that political correctness would have on literature. But novelists are not the only ones who have caught the attention of sensitivity readers. Fiction’s new moral guardians have now taken aim at the world of cookery books.

Last year, The Times reported that Jamie Oliver uses ‘teams of cultural appropriation specialists’ to review his recipes in an attempt to make sure they do not ‘offend anyone’. His ‘empire roast chicken’, which the chef said you can eat with your hands, along with his ‘punchy jerk rice’, were both previously deemed offensive to the Indian and Caribbean communities. In 2018, Labour MP Dawn Butler took to Twitter to voice her opinion. The former shadow equalities minister tweeted, ‘Your jerk rice is not ok. This appropriation from Jamaica needs to stop.’ Initially, the Essex-born chef did the right thing and defended himself, telling Hello! magazine (as reported in the Daily Mail) that ‘authenticity’ was a word that should be used ‘very carefully as most of the things we love…are not what we think they are.’ But the damage was done. By supposedly stealing other people’s cultural heritage for commercial gain, Oliver’s critics were basically accusing him of a bizarre form of culinary colonialism.

I would argue that Oliver uses ‘cultural appropriation specialists’ nowadays in order to be financially successful. Shielding your work from offence is the latest way to signal your right-on credentials. And it is a big business. Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) managers command six figure salaries. Get their approval, and the world is yours – they will even open the door for you. Cookery books are one of the most difficult industries to break into in the publishing world. In 2020, 5,000 cookbooks were published; of these, only one-tenth, (556) sold over 100 copies. The ‘Naked Chef’ has sold more than 48 million books. After his chain of Italian restaurants collapsed, Oliver would seem to be trying to protect his empire. (No chicken pun, I promise).

With the possible exception of ‘cultural appropriation’, there is no phrase more idiotic in the politically correct lexicon than ‘lived experience’. Yet within just a few years, this meaningless shibboleth has come to dominate the world of literature.

In recent years, sensitivity readers have become the most talked-about people in publishing. Essentially, freelance copy editors are hired by publishers to review new manuscripts in an attempt to ‘cancel-proof’ new works of literature. They are paid to read books that portray characters that exist outside the ‘lived experience’ of the author. For example, the white Canadian author Paul Carlucci had a publishing deal fall through after a sensitivity reader made a series of objections to his portrayal of an Indigenous character from the Canadian Odawa nation. Carlucci felt that the increasing list of objections would have ruined the character development and narrative flow of the novel, telling The Sunday Times, ‘I got their notes—and they were ridiculous… If I’d followed this advice I would have portrayed an 1830s Canada that is more racially just than it is today. It would have been sanitised.’

Sensitivity readers are a modern version of a centuries-old problem. These self-appointed censors are not a new phenomenon. Literature has had a long and bloody relationship with the written word.

When William Caxton introduced the printing press to England in 1476, it revolutionised the world of literature. It helped spread ideas and opinions wider and faster than ever before. The response from successive English monarchs was to control it. Long before Orwell, they realised that he who controls language has power. Henry VIII established Crown licensing of the press in 1529. It meant nothing could be published without the express permission of the Star Chamber—a network of judges and privy councillors. Anything critical of the Crown or the Church could be branded treason or seditious libel.

Fifty years after Caxton, William Tyndale printed an English version of the New Testament in Germany. When he brought it to England in 1526, it was immediately proscribed. Ten years later, he had not yet finished his translation of the Old Testament when he was captured in Antwerp, before being tried, strangled and burnt at the stake for the crime of heresy. Yet just three years later, Henry VIII split from Rome and founded the Church of England, thereby giving his approval for an English text.

In 1663, John Twyn was hanged, drawn and quartered at what is now Marble Arch for printing—not writing—a book justifying people’s right to rebel against injustice. The system of Crown licensing finally ended in 1695. All it took were the deaths of a few revolutionaries and a passionate plea from John Milton, set against the backdrop of a protracted civil war. Give me liberty or give me death!

As history has shown, our relationship with the state has often been bloody, especially when we have fought so hard for our civil liberties. But it is not just the state that imposes top-down collective control over our right to speak freely. Censorship can often come from other, less abstract relationships much closer to home. A lighter touch was required. Think less iron fist, more velvet glove.

When we reach the 18th century, we enter a new, less violent era of censorship. In 1779, Frances Burney wrote a play called The Witlings. The comedy satirised modern society. Despite this, it was not performed or printed for almost two hundred years. It was censored and suppressed by what she called her ‘two daddies’, her father, Dr Charles Burney, and her ‘elderly friend and literary censor’, Samuel Crisp. Censorship had found a new home in Georgian high society.

Henrietta (known as Harriet) and Thomas Bowdler found themselves, somewhat ironically, contributing to the English language when they edited The Family Shakespeare in 1807. They went through some twenty works of the Bard and removed all ‘words and expressions…which cannot with propriety be read aloud in a family.’ The practice became so widespread that it led to the creation of a new verb: ‘bowdlerise’, that is, to alter and remove offensive language from a literary work – thereby reducing its creative impact.

As censorship became acceptable among the upper middle classes, it also increased in frequency. It was still going strong last century; James Joyce’s Ulysses, which turned 100 last month, was banned in the United States before Joyce finished writing it. Meanwhile, in 1960, the Old Bailey—a court normally reserved for the most serious cases of murder and violence—found itself presiding over the ultimate crime of words: giving offence. Penguin Books was put on trial for publishing Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and was eventually acquitted. Yet there is a tragic irony to all this. Puffin is a subsidiary of Penguin Books. Some sixty years after the Lady Chatterley debacle, Puffin is now doing a similar thing to Roald Dahl – proving that we have not learned anything from history.

Contrary to popular opinion, Dahl has not been ‘cancelled’: the original text will continue to be published, after a climb-down by Puffin. But that misses the point. The fact that the publisher at first simply tried to replace the originals, and the public outcry against this move, shows how much we take freedom of expression for granted. The censorship of all art, literature, painting and music is an attempt to eradicate the past and impose a single, politically driven narrative on history. Worse, giving someone permission to do this is nothing short of cultural vandalism. It shows a profound ignorance of history and a tragic misunderstanding of liberty that fewer and fewer of us seem to share. Such ignorance is what led to Edward Colston’s statue being tipped into Bristol harbour.

There are signs of a pushback. Later this year, Carlucci’s novel will be published by Swift Press, a new, independent publisher specialising in cancelled authors and books that other publishers will not touch. Swift Press sold 100,000 books within the first nine months of 2021. Scrolling through its list of authors, one notable name stands out: Kate Clanchy. Sensitivity readers censored her Orwell prize-winning memoir, Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me. Despite the prize, the book caused controversy after critics accused her of using racial stereotypes and ableist language. She eventually parted company with her original publisher, Picador, and had the book reissued by Swift.

Roald Dahl was a wonderful writer whose books have now sold in excess of 250 million copies worldwide. Children love them because they are drawn to the surreal and the grotesque. For them, to see authoritarian adults in all their physical and moral hideousness can have a certain rebellious charm. Dahl’s writing can be a means of catharsis.

Children quickly learn the difference between literal and other interpretations of words. As such, Puffin’s attempted censorship is an insult to both their creativity and sophistication. With these edits, children are being taught not to see the ugliness, the strangeness and sometimes even the horror of the world around them – to pretend it does not exist. That is a story truly more sinister than anything Dahl could create.

Enjoy this article? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on freethought.

2 comments

Great article. It seems that people take offense too quickly these days. Once you start updating yesteryears texts, where do you stop? Bravo Noel Huxley for writing a considered piece on the need to leave texts intact so as to reflect the period that they were written in.

I enjoyed your article. This woke culture has gone too far. I call it “stealing offence” when offense is taken when it was not given. People will scan some writing, and completely miss the thrust of the argument and call out the author for using a certain word. I have been a victim of this myself. After writing a comment about how I enjoy black music and how most popular music owes a huge debt to it, with its origins in the delta blues and negro spirituals, I was called a racist for using “negro”. My argument clearly showed that I was very much supportive of the black people and culture, but they were triggered by a word, used in a perfectly correct historical context.

Dahl was “of his time”. Some of his introductions to Tales of the Unexpected are sexist, and racist, but I would never want to see them removed. They reflect the pervasive attitudes of his time, and only jar today because we have progressed. How on earth is “terrifically fat” more offensive than “tremendously flabby”? This demonstrates just how stupid this is. Two phrases that mean the same, but one is deemed offensive. I personally find the current trend of legitimising being fat to be offensive. As someone who used to be skinny, but is now overweight, I don’t like it. I don’t like being fat, I battle with it, but I am fat, not terrifically, but I’m definitely fat. I don’t want some probably skinny, woke millennial taking offense on my behalf – that’s patronising and offensive in itself. I find my own fatness offensive, and I have no problem with other people finding it offensive too. Obesity is not good. It is life threatening, it puts as much strain on the NHS as smoking used to, and it would serve humanity better, if these people were to focus on changing the obesity culture, rather than changing language in order to make obesity acceptable.

Comedians have been attacked by able-bodied people for making jokes about conditions like MS, yet praised by MS sufferers for laughing at the condition, not the person. People should stop stealing offense on behalf of others, and look into fixing their own addiction to the endorphin rush they get from berating someone who made a perfectly innocent comment.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate