The next President of the United States will be in office during the Semiquincentennial, which will mark 250 years since the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. As a British and Irish citizen with affection for American culture and institutions, as well as an historian of atheism in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, I for one am looking forward to the festivities. The commemoration will be an opportunity, not just to reaffirm the ideals of liberty and democracy upon which the nation was founded, but also to reinvigorate ways of thinking that can help to set out a vision for the future. At present, the non-partisan America250 organisation is already planning a range of events, exhibits, contests, and publications, that it is hoped, by the conclusion of the commemoration year, ‘will have ignited our imaginations, elevated our diverse stories, inspired service in our communities, and demonstrated the lasting durability of the American project.’

In that spirit, we might also celebrate the occasion by drawing on a rich tradition of freethought that has roots in the revolutionary period and has resonated across successive generations. The aspirations of free enquiry, secularism, and resistance against tyranny helped to create the United States. To rediscover these principles and put them into practice for the benefit of all, freethinking should once again play a central role in the public history and cultural memory of the American Revolution. No matter who takes the Oath of Office in January next year, I’m sure that the following suggestions will reach the top of the Resolute Desk in-tray pile in no time.

We might begin by looking back at a previous anniversary of independence as an instructive guide to the possibilities and challenges that freethought presents, and the role that it can play in the upcoming celebrations. In anticipation of the Centennial Exhibition at Philadelphia in 1876, one hundred years after the Revolution, a group of freethinkers petitioned for ‘a colossal bust of Thomas Paine’ to be constructed for placement in the memorial hall. The document, held at the Library of Congress, not only advocates for the pivotal role of freethought at the nation’s inception but also testifies to its enduring importance as a lens through which successive generations have understood the significance of the United States.

Notably, Paine himself had linked independence and democracy with freedom of thought and secularism. In his rallying call for American independence, Common Sense (1776), he railed against monarchy as ‘the most prosperous invention the Devil ever set on foot for the promotion of idolatry’, reserving special ire for that toxic, self-aggrandising mixture of religion and politics that can conceal, yet never cure fallibility and mortality: ‘How impious is the title of sacred majesty applied to a worm, who in the midst of his splendor is crumbling into dust.’ As if to leave no room for equivocation on the matter, appended to his pamphlet was an address ‘To the Representatives of the Religious Society of the People called Quakers’, in which Paine expressed the hope ‘that the example which ye have unwisely set, of mingling religion with politics, may be disavowed and reprabated by every inhabitant of AMERICA.’

Celebrating ‘The Author-Hero of the American Revolution’, the petition for 1876 emphasised the significance of Common Sense, in which Paine had ‘first, and before all others, proposed the Independence of the American Colonies. … He asked for a Declaration of Independence. He created a desire for it.’ The petition went on to argue that Paine had ‘taught the masses that Independence was not only a possible, but a probable condition’, adding that ‘His writings were as necessary to the army as its [cannon], and [almost] as formidable.’

The support that formidable freethinking writers and activists such as Rose and Wixon lent to honouring Paine’s legacy testifies to their preoccupation with renewing history for the present and the future.

Among the signatories to this petition were Ernestine Rose and Susan Wixon, each an important proponent of radical change in her own right. Born in Poland, the Jewish freethinker Ernestine Rose travelled to Berlin, Belgium, the Netherlands, and England before emigrating to the United States in 1836, where for three decades she campaigned for an internationalist vision of women’s rights and advocated for the abolition of slavery, becoming a renowned orator. She repudiated scriptural authority, criticised religious institutions, and rejected ‘a personal God’. Meanwhile, the New England teacher, school board member, and writer Susan Wixon advocated educational and labour reforms, challenging religious models of education by producing children’s literature that promoted independent thinking, scientific understanding, and ethics.

The support that formidable freethinking writers and activists such as Rose and Wixon lent to honouring Paine’s legacy testifies to their preoccupation with renewing history for the present and the future. Even as they sought to reaffirm a tradition of liberty, republicanism, and freethought that reached back to the revolutionary era, they were actively engaged in pioneering new ways of implementing and communicating tangible changes that empowered their communities and helped to prepare the next generation for the challenges ahead.

Amidst arguments between secularists (in support of Paine) and Protestants (suspicious of infidelity and blasphemy) over which parts of the American Revolution were worthy of celebration and commemoration, the National Liberal League did secure a new marble bust of Paine to be erected at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. According to the Freethought Society, funding for the bust was secured on 4 July 1876, and the sculpting was undertaken, fittingly, by a freethinker of Boston named Sydney H. Morse. The Society offers a telling history of the bust’s movements thereafter: ‘In 1905, the bust was…placed on display at Independence Hall. By 1926, the bust was refused a niche because according to the powers that be, Thomas Paine was “an infidel.” City Council members declared that Thomas Paine was “immoral.”’ Apparently, the bust now resides in the office of the Executive Director of the American Philosophical Society, inaccessible to the public save for pre-arranged appointments.

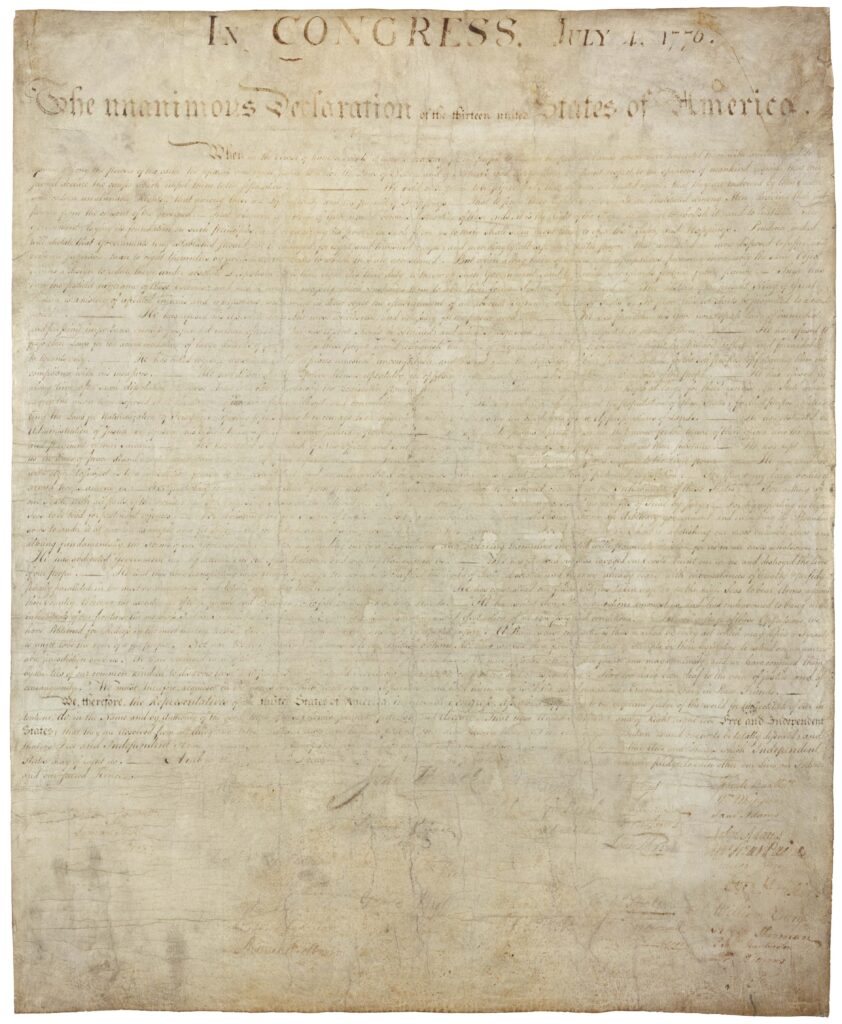

While the bust of Paine hardly committed blasphemy as feared among religious critics, much less the ‘idolatry’ that the ‘Author-Hero’ himself had derided, there is a degree of irony in the near-sacred monumentality that freethinkers have bestowed upon a fellow advocate of secularism. This is a poignant theme in the late Pauline Maier’s magnificent book American Scripture, which suggests that the solemn reverence afforded to the Declaration of Independence itself in the years since the Revolution has been somewhat misplaced; thinking of the document as ‘scripture’ not only obscures the political messiness and linguistic wrangling through which it was drafted and edited, but also sits uneasily with the secular principles of the nation whose birth it announced. As Maier wrote, commenting upon the current location of the Declaration at the National Archives in Washington DC, sequestered within a reliquary-esque display case:

Why should the American people file by, looking up reverentially at a document that was and is their creation, as if it were handed down by God or were the work of superhuman men whose talents far exceeded those of any who followed them? The symbolism is all wrong; it suggests a tradition locked in a glorious but dead past, reinforces the passive instincts of an anti-political age, and undercuts the acknowledgment and exercise of public responsibilities essential to the survival of the republic and its ideals.

None of this is to suggest that political leaders should neglect the founding documents, rendering them inert through apathy or contempt. The aspirations of the Declaration, along with the provisions of the Constitution, are precious, and their integrity must be preserved, particularly amidst the ongoing threat that election deniers and demagogues pose to norms and institutions at local, state, and federal levels. We must preserve them, though, not by treating them as sacred artefacts, but by understanding them as part of an ongoing conversation that is taking place at every level of public and civic life.

This is itself a tenet of freethought that has motivated generations of radical writers and activists trying to work through the dynamics of church and state relations, challenge the apparatus of religious privilege, and navigate the moral challenges of economic and political development. Indeed, radicals and freethinkers often looked back on the ideals of the Declaration and the Constitution to demand that rights be expanded and injustices overturned in their own day. Frederick Douglass is a shining example here; see his 1852 speech ‘What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?’ In a recent work, the philosopher Matthew Stewart has noted the telling difference between William Lloyd Garrison’s anti-Constitution abolitionism—for him, the Constitution was a ‘compact with the devil’—and the abolitionism of Douglass, Theodore Parker, Lincoln, and others, who admired the leaders of the revolutionary era and the ideals they set forth, despite their hypocrisies and failures. For such radicals, the Declaration and the Constitution were not inert, sacred scriptures but living documents capable of inspiring and subject to revision. Rather than rejecting the ideals of the Declaration, Douglass wanted them to be fully realised. Recovering this way of thinking can imbue the ideas and arguments of the revolutionary era with new immediacy and application.

Marbled monuments to the revolutionaries can play an important role, capturing the imagination by bringing us face-to-face with the past.1 Likewise, people should be able to depend on the preservation and accessibility of their country’s founding documents in a public forum where everyone can see and read them. As important and enriching as returning to these statues and studying the original texts might be, however, my advice ahead of the Semiquincentennial is more practical. It is addressed to any citizen interested in rejuvenating the roots of free enquiry and democracy. It is as follows: make the history of freethought in the United States not only a talking point but also a starting point.

Yes, of course, talk. Should the chatter turn to politics or religion, by all means surrender to convention and change the subject, but if you can, change it to history—the messiness and accidents and contingencies and unknowns and adventures and possibilities of American history, to be precise. Talk about the Declaration of Independence, and the great, precipitous risk it represented. Talk about the promises and limits, hopes and failures, of the nation’s founding vision. Then, strike up conversations at your local taverns and coffee shops about your community’s history, its present struggles, and its emerging needs. These are the places where it all started, among people who understood that in order to think for ourselves, we have to talk to each other.

At this moment, the need to think, communicate, and act effectively, productively, and with conviction, yet open-mindedly, alert to differences of opinion, and eager to persuade, could not be greater.

But don’t just talk. Start to plan and implement. Traverse the public square mindful that it is often the very ground upon which profound grievances have been voiced so that civil rights might be claimed and won. Figures like Paine, Rose, and Wixon are proof that freethinkers are at their most effective when they develop a credible case for tangible action and are able to demonstrate why free enquiry, secularism, liberty, and democracy matter to the lives of ordinary people. Research local issues and causes, support policies and reforms that reflect your values, and encourage like-minded people to lend a hand, while also seeking to better understand points of view with which you disagree.

The opportunities are already there. Democracy saturates life in the United States. Although the presidential election pervades, important developments unfold at every level: elections determine representation in federal, state, and local legislatures; ballot initiatives decide policies on everything from healthcare to housing; school boards shape education; to say nothing of gubernatorial elections, mayoral elections, county and city council elections, recall elections, and the elections of sheriffs and some police chiefs.

At this moment, the need to think, communicate, and act effectively, productively, and with conviction, yet open-mindedly, alert to differences of opinion, and eager to persuade, could not be greater. Freethought offers a way of discussing, writing, arguing, and living that meets this moment. It is both principled and dynamic; robust in its fight for moral clarity and direction, but perceptive to change, admitting of uncertainty, and open to self-criticism. It is no coincidence that these are also enduring features of American democracy: experimental and scrutable, yet daring and defiant. Should the United States strive more fervently towards inscribing these ideals in hearts and minds as well as on paper and in stone, the next 250 years of the nation’s history will be all the more worthy of celebration.

- Editor: As it happens, the Thomas Paine Memorial Association has recently succeeded in gaining approval from the National Capital Memorial Advisory Commission to erect a monument to Paine in Washington, DC. I was proud to submit written testimony in support of the plan. ~ Daniel James Sharp ↩︎

Related reading

Books From Bob’s Library #1: Introduction and Thomas Paine’s ‘The Age of Reason’, by Bob Forder

Books from Bob’s Library #2: Thomas Paine’s ‘Rights of Man’, by Bob Forder

The rhythm of Tom Paine’s bones, by Eoin Carter

The radical atheism of the American revolutions: interview with Matthew Stewart, by Daniel James Sharp

‘Project 2025 is about accelerating the demise of a functioning democracy’: interview with US Representative Jared Huffman, by Daniel James Sharp

Donald Trump, political violence, and the future of America, by Daniel James Sharp

Donald Trump is an existential threat to American democracy, by Jonathan Church

White Christian Nationalism is rising in America. Separation of church and state is the antidote. By Rachel Laser

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate