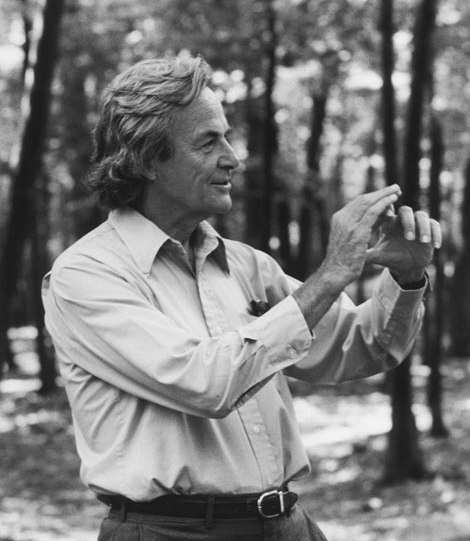

In 1986, before a live television audience of millions, the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after launch. It is a moment that those watching will never forget. Even though I was a child at the time, I still remember my mother’s sadness at the tragic loss of the brave crew, including schoolteacher Christa McAuliffe. The investigation committee featured my favourite scientist in history: physicist and Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman.

Feynman’s strange journey with the investigation is chronicled in his book “What Do You Care What Other People Think?”: Further Adventures of a Curious Character. His journey ended with an appendix added to the final disaster investigation report, which finished with the immortal quote: ‘For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.’

Though, as Einstein and Whitehead are believed to have implied, science progresses in the direction of the worldview of those practising it, ideology can never win against reality. Reality is undefeated against every discipline across the annals of history.

I have written before about the problematic rise of science denial, science scepticism, and conspiracy theory. A great deal of current philosophy, very much in vogue among academic elites influenced by the French intellectuals of the twentieth century, holds that science is just a story told by the patriarchy (and/or other oppressive forces) to control minorities and uphold white Western male privilege. Science is simply another Western narrative, and one responsible for violence at that. According to this mindset, science must be brought in line with other narratives and subjected to decolonization, deconstruction, and every other tool of the postmodernists so as to make it adhere to a better story. The implications of this view for the world are obvious and deeply alarming. Science is not merely a story. It is a method of investigating the world ‘out there’, which exists in a certain way whether we like it or not. It seeks to understand the underlying fabric of nature, which would be the same whether we existed or not.

Perhaps the worst example of ideologically driven science comes from the Soviet era. Trofim Lysenko, the chief ideologue of Soviet agriculture, declared that mainstream genetics and molecular biology were the sciences of the bourgeois capitalist nations. He was applauded for his view that grain could be trained according to communist principles. To him, much as humans could be strengthened by communism, the seed and farmland could be strengthened through ‘vernalization’. This included seed being toughened by being run through cold water in order to assist it in growing all year round, including during the harsh Soviet winter, a process which would supposedly be passed on to the next generation in Lamarckian fashion. He incorporated communist ideology wherever he could, including planting seeds too close together out of a belief that plants in their natural state would not compete due to their inhabiting the same ‘class’.

This ideological science was a disaster of epic proportions, leading to the deaths of millions of Soviet citizens from famine. Lysenkoism also contributed to the Great Chinese Famine after Mao’s China adopted it as an official ideology in 1958. That famine killed between 15 and 55 million people. Lysenko did not relent and thousands of dissenting Soviet scientists were imprisoned or executed. It took decades to undo his suppression of genetics, which left Soviet science lagging far behind the rest of the Western world for a long time.

Feynman was right—nature cannot be fooled. Reality must take precedence.

In 2021, Richard Dawkins embarked on a battle against the incursion of indigenous ‘ways of knowing’ into the high school science curriculum in New Zealand. He penned a letter to the Royal Society of New Zealand for not doing enough to stand against this incursion (‘Creationism is still bollocks even if it is indigenous bollocks’). In 2023, during a visit to New Zealand, he ‘walked headlong into [the] raging controversy’, continuing his quest to return science to its normal pursuit of truth. Dawkins was aghast, as many of us were, that a 21st-century Western nation built on Enlightenment values could divide its science curriculum to include myths of indigenous peoples as if they were equally valid forms of exploring the workings of the natural world. This was nothing but a return to pre-Enlightenment, pre-industrial times, when the world was understood through mythos and tradition.

Postmodern philosophers are free to interject in discussions about science and lambast it as an oppressive structure, all the while writing on their tablets, giving visiting lectures over Zoom, and posting on social media—logical contradictions and circular reasoning are narratives invented by the patriarchy, anyway. And sociology of science is free to investigate science as a purely human enterprise, replete with too many men and not enough decolonization. But the inconvenient truth is that reality always wins.

The naked emperor is revealed every time the sick go to the doctor and not the witch doctor to treat their cancer, or when they take antibiotics rather than accept pseudoscientific treatments for their infections, or when medical science, rather than gurus, is consulted during a pandemic. When one’s life is on the line, people gravitate towards reality.

What is reality? That is still a question for science above all. Metaphysics can address the nature of ultimate reality, but one cannot answer the whole question without some recourse to science, at least not without any hope of being correct. Epistemology can tell us that this may well all be a dream or simulation, and yet our shared experience requires scientific data as a reference point.

Sir Arthur Eddington distinguished humorously between reality and reality (loud cheers) in his best-selling work The Nature of the Physical World (1928). Writing about how Einstein’s relativity had turned our understanding and interpretation of the world away from the simplistic and towards the technical and mathematical, he described the difference as stranger than we could ever imagine. The world was no longer simple and ordered; indeed, it was deeper, broader, and vaster. Reality (loud cheers) meant for Eddington a statement of the real backed by an emotional appeal to an audience, as when a politician declares that a new dawn is set to become a reality. Eddington spoke of being afraid of the words ‘existence’ and ‘reality’. Reality remains objective in physics, due to its narrow scope and clear, shared definitions. Relativity and quantum physics had shaken the very ground beneath us but had rendered the mathematical world more accurate than ever.

No one can survive a post-truth world.

Somewhere in the past few years, reality (loud cheers) seems to have over-encroached upon reality. But louder cheers do not superimpose over reality itself. Indeed, it does not matter how loud the cheers become, reality always wins, and nature cannot be fooled.

No one can survive a post-truth world. Truth, reality, or whatever one may wish to call it will never go away. Science can be suppressed and scientists can be silenced, as the career of Lysenko demonstrates. The results remain the same, whether in China, the Soviet Union, or our modern context. When deciding to travel by boat from the North Island to the South Island of New Zealand, one can use meteorology to ascertain the weather conditions, currents, and tides. One can also consult the gods and conjure up favour from them. Most people, if they are sane, will choose the former, and they will always have superior results in the form of a safer journey—because nature cannot be fooled. And either way, one will use a boat built by modern engineers.

I sincerely hope that our students learn the lessons of history and heed the advice of the timeless Richard Feynman (assuming this history is approved).

Related reading

A farewell to Dawkins? by Samuel McKee

Faith Watch, February 2024, by Daniel James Sharp

1 comment

The idea that “reality always wins” emphasizes that, despite temporary distractions or illusions, the natural course of events remains unchanged, and reality, in the end, is what truly defines our experiences. This serves as a reminder to stay grounded and connected to the fundamental truths of life, even when external forces attempt to sway our focus.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate