December is Ex-Muslim Awareness Month so this week, while much of the world’s focus is on Christmas and elsewhere, the Freethinker is publishing articles highlighting the underknown plight of ex-Muslims in Britain today.

I try to carefully ration my invocations of 1984. Working at the Free Speech Union, where we routinely see people hounded out of their jobs for wrongthink—or, increasingly, imprisoned for social media posts—in a country where the police keep hundreds of thousands of records of ‘non-crime hate incidents’, it’s getting quite difficult. It’s hard not to see shades of Orwell’s nightmare everywhere you look.

It’s frustrating that so much of the language of 1984 has now become cliché. The novel’s warning risks being diluted by the omnipresence of thought crime and wrongthink and the rise of thought policing. But occasionally, something is so startlingly reminiscent of the plight of Winston Smith that the invocation is unavoidable, and the raw, original power of 1984 can be felt once more.

As it did when I spoke with Farah, aged 18, during the three years I spent studying the plight of ex-Muslims in Britain. The reader must forgive—and will soon understand why—this is not her real name.

Farah had spent her teenage years in a heavily Muslim area somewhere in Britain. For reasons that will become obvious I will not say where this was. She had the perspicacity, and perhaps the misfortune, to realise that her religion, the faith she’d been raised with, wasn’t true. The consequences of this anti-revelation were profound.

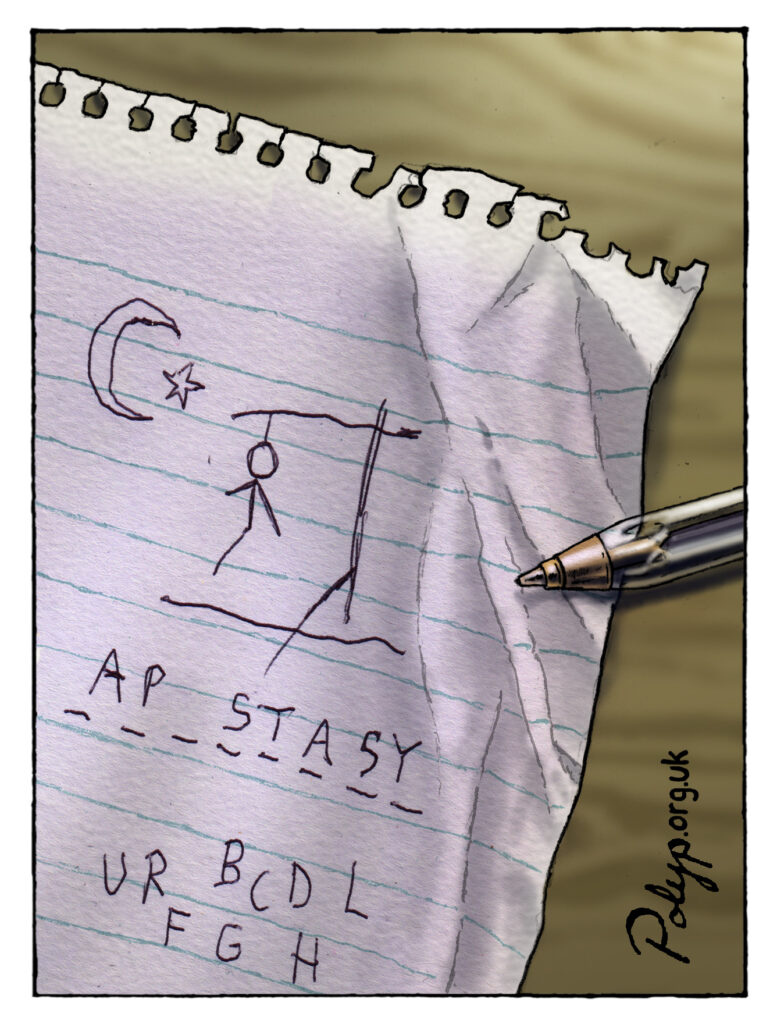

It’s hard to imagine what it must be like to sit in a service in a mosque, pretending to believe. To wear a hijab—or worse, a face veil—while silently raging against the oppression of women and girls within the normative Islamic tradition. To know that any expression of dissent, any sign of apostasy, could have severe or even dangerous consequences. This was the situation Farah endured, as one of countless secret apostates living in Muslim areas of Britain.

She told me:

I live in a very Muslim area and it’s impossible to detect other ex-Muslims. Since you can’t just go up to people and ask them if they’re ex-Muslim. The process of finding other apostates in real life parallels 1984, it’s like when Winston observes other characters looking for signs of “unorthodoxy” that would prove that they’re against the Party.

Farah described her desperate search to find anyone else like her, anyone who would understand: ‘Maybe, that hijabi who is too passionate about women’s rights is an apostate? Or that guy who attends every Friday prayer? You don’t really know.’

In 2016, a report on integration in Britain found that religious and ethnic segregation was so stark that some Muslim school pupils believed the population of Britain to be about 90% Asian: such was their experience of day-to-day life, and their isolation—perhaps it would be more accurate to say their partition—from wider society. Needless to say, things have not got better in the intervening eight years. In an Islamic enclave like this, a secret apostate like Farah has almost no lifeline to the outside world. She told me forlornly that she had heard of ex-Muslim groups who met in person in big cities—albeit they had to take strict security precautions and intensively vet new attendees to ensure they were not infiltrators with ‘dangerous motives’. But such groups were far beyond her reach.

Over time, she dared to tell some non-Muslim friends the truth. She had not dared tell any Muslim; the risks were too great. In total, only four people knew the truth about Farah. I was to be the fifth.

Farah was one of 25 former Muslims in Britain whom I interviewed for my doctoral research on apostasy within Islam. As many as 7% of children raised as Muslim abandon Islam by or during adulthood. This is a tiny figure compared with rates of apostasy for children raised in Christian homes, but in raw numbers, it is a sizeable block.

A large part of the terrifying exhilaration of Winston’s clandestine meetings with Julia is sex: a covert, unregulated relationship beneath—so they hope—the Party’s gaze; a relationship which is a threat to the Party’s power because of its privacy, because of its personal loyalty. And so it often is with ex-Muslims. My interviewees told me about their betrayal by siblings for pre-marital sex or for having a relationship with a white non-Muslim and of being outed as gay or lesbian, and of the usually severe, and sometimes terrifying, consequences of subverting the Islamic order through an illicit relationship.

Not only must these ex-Muslims keep their apostasy a secret, but they must also hide their relationships, their loved ones, and the most fundamental parts of their lives. I’ve heard so many stories like this, and I still struggle to understand what it must actually be like to live in a state of such total repression, where you cannot voice your opinions, express your beliefs, meet with likeminded people, have relationships or a normal family life, speak your mind, or love, or even dress, how you wish. For ex-Muslims, every possible human right is infringed and suppressed under the heavy weight of Islam, pervading, as it does, every aspect of life.

This is all happening in Britain. The extent of the regression of individual freedom in Britain is for nobody more acute than it is for ex-Muslims. Their experiences cannot be ignored: if their freedom is infringed, then everybody’s is. If they cannot criticise Islam freely, then nobody can.

Some ex-Muslims do escape, often at the cost of complete ostracism from their family, friends, and entire communities. A courageous and growing number have begun, since the 2000s, to speak about their experiences publicly. But an unknown and unknowable number of ex-Muslims in Britain live like Winston Smith and Farah. For a handful of them, speaking to me, a stranger, was the only occasion on which they had ever spoken honestly about their lives and their beliefs.

There are very few reasons to be hopeful, but there are some. The ex-Muslims I spoke to had to do the hard work of discovering the Enlightenment tradition for themselves. It was not handed to them; indeed, they were shielded from it. In many ways, they represent an example to a Western world which has forgotten where it came from and left its values undefended, neglected, and betrayed for far too long.

Related reading

Time to step up and support #ExMuslimAwarenessMonth, by Khadija Khan

Breaking the silence: Pakistani ex-Muslims find a voice on social media, by Tehreem Azeem

Surviving Ramadan: An ex-Muslim’s journey in Pakistan’s religious landscape, by Azad

The Galileo of Pakistan? Interview with Professor Sher Ali, by Ehtesham Hassan

Mind Your Ramadan! by Khadija Khan

From religious orthodoxy to free thought, by Tehreem Azeem

‘The best way to combat bad speech is with good speech’ – interview with Maryam Namazie, by Emma Park

The far right and ex-Muslims: ‘The enemy of my enemy is not my friend’, by Sara Al-Ruqaishi

1 comment

At the age of 16, In 1977 I told my deeply Christian mother, that I didn’t believe in God and wasn’t going to go to church anymore.

Her reply was, “That’s all right dear. I’ll always love you and I’ll always pray for you.” Which she did right until her death two years ago. It’s obvious that such a gentle path is not available to all.

Our societies should protect freedom from religion as well as freedom of religion, but especially in the case of Islam we don’t.

I wish Farah and her friends all the best. You’re much braver than I needed to be all those years ago.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate