Historians and neuroscientists can speculate why particular formulations of the afterlife evolve in different cultures but visions of life after death must always be ones of imagination. When I was writing my Children of Athena (which deals with Greek intellectuals under the Roman empire), I found that my subjects had an undogmatic sense of the beyond whether they believed in the traditional Greek deities or some form of philosophy. Free of dogma, these intellectuals had created a harmonious relationship with their spirituality, a spirituality which I believe is natural to humanity.

Christianity transformed this imagined beyond into dogma. Christians teach that there is an afterlife of supreme importance and that it can be set out in meticulous detail—as shown, for example, in Dante’s Divine Comedy. Even the nature of humankind, as in Augustine’s concept of original sin which he believed was inherent in every human being, influenced the way that one might be treated in the afterlife. Followers of Augustine talk of eternal hell fire for those who are not offered the grace of God, although a few might be admitted to the glory of heaven. Spiritual harmony, possible for each individual if left to themselves, vanishes unless one surrenders to faith.

In his major and well-reviewed history of Christianity, Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind (2019), Tom Holland describes the apostle Paul’s abrupt conversion and his distinctive (and idiosyncratic?) contribution to Christianity which followed, despite the frustration shown in his letters when early Christians did not keep to his path (Galatians 3:1: ‘O you poor and silly and thoughtless and unreflecting and senseless Galatians!’).

But were there Christian paths, independent of Pauline authority, not chosen? What happens if hitherto lost letters of Paul are found (as other caches of ancient documents have been) and his theology needs revision? Where does his authority based on the canon of authentic letters then lie?

The Greek aptitude for debate was shown in the tumultuous and bitter arguments in the early church councils. Understandably, the assembled bishops could not agree on the nature of Christ and his relationship with his supposed Father. Further debate erupted over what one had to do to be saved—perhaps God, as omnipotent, knew already, so a believer’s fate was sealed. This had important implications for free will. The freely imagined state of the afterlife transformed into dogma would appear to be a philosophical (or, in other words, theological) absurdity but historians can show how, in the fourth century CE, the emerging religion was taken over by politics. Only the power of a Roman emperor could bring order to a council and effect a defined solution which was inevitably political.

None of these alternative paths nor the evolution of Christian dogma is covered in Dominion. Holland is a distinguished classicist, and his many books offer a readable and authoritative introduction to the ancient world. Despite being outside his comfort zone, Dominion has been a bestseller. Part of this is due to Holland’s massive research and vivid prose but also due to his argument that Christianity has led to many of the ethical values which are accepted as central to Western thought. (In other parts of the world, Christianity has resisted these ethical values, so the trend is not universal—and perhaps this is telling.) A secular historian who champions Christianity in this way is bound to be popular at a time when religious belief is under threat.

Dominion is divided into chapters which trace a broadly chronological, as well as thematic, story. For instance: Chapter Three, ‘Mission, AD 19: Galatia’, Chapter Four, ‘Belief, AD 177: Lyon’, Chapter Five, ‘Charity, AD 362: Pessinus’, and Chapter Six, ‘Heaven, 492: Mount Gargano’. I am particularly interested in his time frame from AD 19 to 492, as it was during this period that many features of an authoritarian Christianity were set down as orthodoxy—a development far removed from the more open and fluid minds of the Greek world.

In the fourth century, the emperor Constantine (r. 306-337) realised that he had to compromise with the burgeoning Christian communities in the cities. He proclaimed that his victory in 312 over a contender for emperor of the Western empire had been accompanied by the vision of a cross emblazoned with the words ‘By this cross conquer’. This tied the success of Christianity to war.

More fundamentally, Jesus had been a rebel against the empire—something that was unacceptable for a Roman emperor determined to assert his authority. Summoning a council of Eastern (Greek-speaking) bishops to Nicaea in 325, Constantine accepted one theological possibility: that Christ was, from the moment of God’s existence, subsumed into the Godhead—the term used was ‘consubstantial’—and thus removed from the humiliation of crucifixion at the hands of a Roman governor.

However, many bishops regarded the Son as subordinate to the Father and argued that he was created later than the Father (rather than simultaneously). The debate continued until the emperor Theodosius I (r. 379-395) decreed in 381 at the Council of Constantinople that God the Father, Christ the Son, and the Holy Spirit formed a Trinity and that only bishops who adhered to this formula could hold office (the rest were ‘demented and insane’ heretics). Ten years later Theodosius banned all pagan shrines. The Olympic Games, which honoured Zeus, were held for the last time in the 390s.

This distinction, between speculative free thought and the acceptance of dogmatic authority, was a revolution in Western thought, a closing of the Western mind. In the Greek world, one did not have to believe in any one of the many philosophies on offer: many intellectuals picked and chose from several. In the Christian world, disbelief in (or acceptance of a heretical interpretation of) the decreed Trinitarian orthodoxy condemned one to eternal suffering. Holland does not even mention Theodosius or this political revolution, though it is crucial in setting the stage for what follows (see my study of the process, AD 381).

In many ways, Dominion is penetrating about the ambiguities of Christian thought; in other ways, it is not. Holland enthuses, rightly in my opinion, about the brilliance of the Alexandrian Origen (c. 185-c. 253). Yet a few pages later he mentions that Origen was declared heretical, but he does not consider what this might tell us about the development of Christianity. Christians have a propensity for crushing any original pathway in intellectual thought. I once read a whole series of autobiographies of Christians who struggled with the conflict between what had been decreed by Constantine and Theodosius and the natural spiritual feelings which are intrinsic to humanity. When, for whatever reason, they eventually gave in to orthodoxy, it was considered a triumph—as if they had finally found ‘the truth’ (or perhaps that should be ‘THE’).

Holland’s book is… a richly textured survey of the Western tradition which wrongly concludes that ‘Western values’, even secularism, human rights, and humanism, evolved from Christianity rather than as a response to it

I found Holland’s expansive prose somewhat trying. It is too discursive for my taste, despite the vast amount of detail which fills each chapter. His treatment of Abelard, the twelfth-century theologian of reason, is outstanding on his personality but fails to explain his importance as a theologian and his lack of impact after his death. Holland asserts that the University of Paris was the result of his influence, but this is stretching his legacy beyond any evidence. The taint of heresy lingered. While Holland deals with conflicts within Christianity, he seldom presents the conundrums inherent in the religion itself and the impossibility of a single Creator God—even if expressed in a Trinity with Jesus as a model teacher in the gospels—as responsible for the variety of human experience.

There is no doubt that Christian theologians are part of the intellectual mix of the Western tradition. Yet, after the Reformation, every national church (Lutheran, Anglican, Dutch, Irish) proclaimed that it alone had the truth. How could they claim otherwise while sustaining their credibility? Conflict between the Christian communities was inevitable. Justifications for slavery were fought out within Christian communities, with many slave owners relying on biblical support. (And, as Matthew Stewart has recently pointed out, the theological and biblical battle over slavery in America was decisively won by the slavers.)

The philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) had lived in Anglican England, Catholic France, and Calvinist Holland so his A Letter Concerning Toleration came from his experience of Christianities at war with each other. Religious toleration arose as a response to Christian intolerance (see Perez Zagorin’s How the Idea of Religious Toleration Came to the West) and in Western Europe, one sees the gradual waning of Christian influence—often abruptly so, as in the recent case of the Catholic Church in Ireland. The more I read about Christianity the more I am aware of the contradiction between the natural spirituality of humankind and the dogma which was formulated by Roman emperors in the fourth century.

In short, Holland’s book is not really a history of Christianity—while it is splendidly readable for many, it is too uneven in its approach. Neither is it a work of theology. Too many philosophical issues about a single God figure are left unexplored. (Holland’s treatment of Thomas Aquinas, surely one of the greatest theologians, especially in the Catholic Church, is cursory.)

It is, rather, a richly textured survey of the Western tradition which wrongly concludes that ‘Western values’, even secularism, human rights, and humanism, evolved from Christianity rather than as a response to it (a response, moreover, that drew on non- and even anti-Christian ideas both modern and ancient).

To assert, for example, that ‘Humanism derives ultimately from claims made in the Bible: that humans are made in God’s image’ assumes that a biblical text had such influence in transforming human minds. Humanism has many roots, some of them in the classical world. That Christianity has upheld power structures and inhumanity in other, more conservative parts of the world is telling. (In any case, what does it mean that man is made in the image of an omnipotent Creator God when humankind is, in some Christian circles, burdened by original sin?)

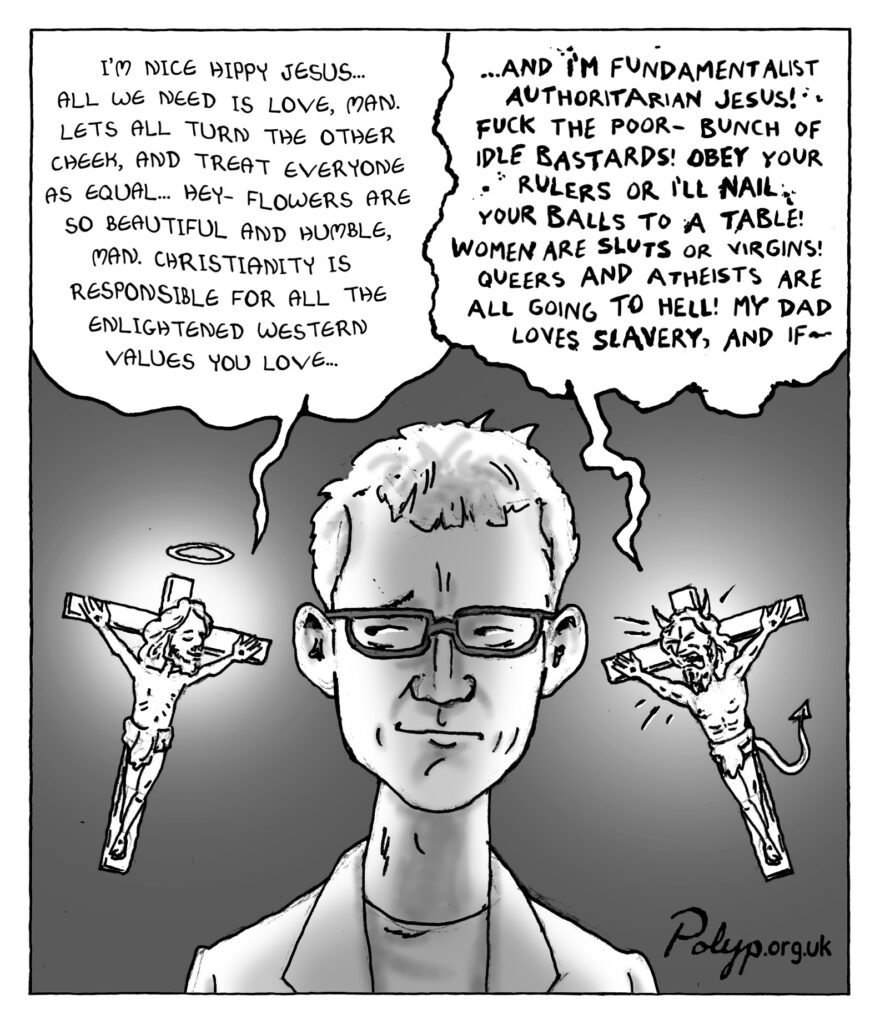

Whether or not one accepts, as Holland does, that Christianity’s historical crimes ‘stand condemned’ by ideals ‘which…are themselves Christian’, it is true that many of those crimes were themselves directly attributable to Christianity (see the point about slavery above). It is no use pretending they don’t ‘really’ count as truly Christian. And if both good and bad can be derived with equal justification from Christian teachings, it is only by appealing to independent thought and other sources of wisdom and ethics that they can be distinguished.

With its determination to assert that Christianity fostered ‘Western values’, Dominion’s success is assured. Yet it is strange that a book centring on the making of the Western mind by a distinguished historian of the classical world neglects the immense contribution of the Romans and Greeks to Western thought. Christianity does not eliminate all previous history, as if it forms the starting point of a dramatic transformation of human experience, nor is it such a totalising force that it is the source of everything in Western thought (especially the good bits, which are, curiously, Holland’s main focus).

The ancient spirit of unrestricted intellectual enquiry, which was revived in the ‘Scientific Revolution’, and many other approaches to ways of thought are inherited from the Greeks. Justus Lipsius (1547-1606) showed the compatibility of pagan Stoicism and Christian ethics. But the fact is that Stoicism got there first. This suggests that ethical values, whether apparently Christian or not, draw on other foundations (Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, for instance). The fact that Christianity still opposes ‘westernisation’ in many parts of the world suggests that the more than a thousand years of classical civilisation in the West deserve to be recognised as contributing to the complexity of Western history—just as much, or more so, than Christianity.

Related reading

‘The Greek mind was something special’: interview with Charles Freeman, by Daniel James Sharp

How the Roman Empire became Christian: Catherine Nixey’s ‘The Darkening Age’ and ‘Heresy’ reviewed, by Charles Freeman

What has Christianity to do with Western values? by Nick Cohen

Do we need God to defend civilisation? by Adam Wakeling

The Enlightenment and the making of modernity, by Piers Benn

Against the ‘New Theism’, by Daniel James Sharp

Can the ‘New Theists’ save the West? by Matt Johnson

The radical atheism of the American revolutions: interview with Matthew Stewart, by Daniel James Sharp

Wrestling with fables: a review of ‘We Who Wrestle with God’ by Jordan Peterson, by Nicholas E. Meyer

A reading list against the ‘New Theism’ (and an offer to debate), by Daniel James Sharp

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate