Introduction

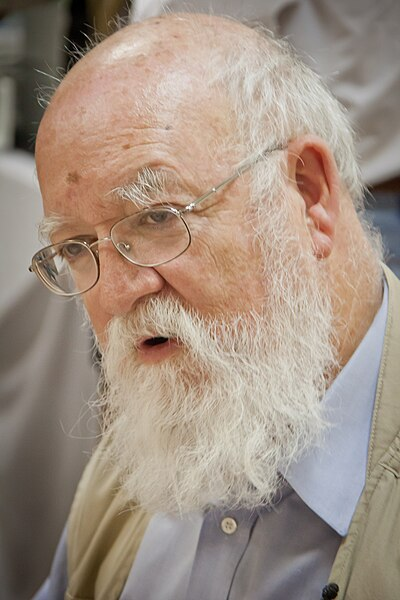

Daniel C. Dennett is Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts University, Massachusetts. One of the world’s best-known philosophers, his work ranges from the nature of consciousness and free will to the evolutionary origins of religion. He is also known as one of the ‘Four Horsemen of New Atheism’, alongside Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Christopher Hitchens.

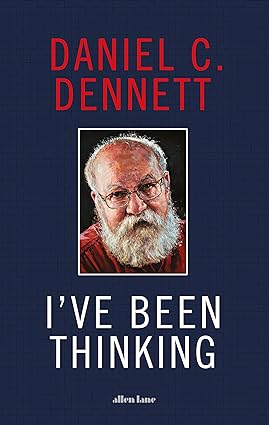

His many books include Consciousness Explained (1992), Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life (1995), Freedom Evolves (2003), Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (2006), Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking (2013), and From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds (2017).

I recently spoke with Dennett over Zoom to discuss his life, work, and new memoir I’ve Been Thinking, published by Penguin: Allen Lane in October 2023. Below is an edited transcript of the interview along with some audio extracts from our conversation. Where some of the discussion becomes quite technical, links to explanatory resources have been included for reference.

Interview

Freethinker: Why did you decide to write a memoir?

Daniel C. Dennett: In the book, I explain that I have quite a lot to say about how I think and why I think that it is a better way to think than traditional philosophical ways. I have also helped a lot of students along the way, and I have tried to help a larger audience. I have also managed to get the attention of a lot of wonderful thinkers who have helped me and I would like to share the wealth.

As a philosopher who has made contributions to science, what do you think philosophy can offer science? Especially as there are some scientists who are dismissive of philosophy.

I think some scientists are dismissive towards philosophy because they are scared of it. But a lot of really good scientists take philosophy seriously and they recognise that you cannot do philosophy-free science. The question is whether you examine your underlying assumptions. The good scientists typically do so and discover that these are not easy questions. The scientists who do not take philosophy seriously generally do pretty well, but they are missing a whole dimension of their life’s work if they do not realise the role that philosophy plays in filling out a larger picture of what reality is and what life is all about.

In your memoir, you say that it is important to know the history of philosophy because it is the history of very—and still—tempting mistakes. Do you mean, in other words, that philosophy can help us to avoid falling into traps?

Exactly. I love to point out philosophical mistakes made by those scientists who think philosophy is a throwaway. In the areas of science that I am interested in—the nature of consciousness, the nature of reality, the nature of explanation—they often fall into the old traps that philosophers have learned about by falling into those traps themselves. There is no learning without making mistakes, but then you have to learn from your mistakes.

What do you think is the biggest and most influential philosophical mistake that has ever been made?

I think I would give the prize to Descartes, and not so much for his [mind-body] dualism as for his rationalism, his idea that he could get his clear and distinct ideas so clear and distinct that it would be like arithmetic or geometry and that he could then do all of science just from first principles in his head and get it right.

The amazing thing is that Descartes produced, in a prodigious effort, an astonishingly detailed philosophical system in his book Le Monde [first published in full in 1677]—and it is almost all wrong, as we know today! But, my golly, it was a brilliant rational extrapolation from his first principles. It is a mistake without which Newton is hard to imagine. Newton’s Principia (1687) was largely his attempt to undo Descartes’ mistakes. He jumped on Descartes and saw further. I think Descartes failed to appreciate how science is a group activity and how the responsibility for getting it right is distributed.

In your memoir, you lay out your philosophical ideas quite concisely, and you compare them to Descartes’s system in their coherence—albeit believing that yours are right, unlike his! How would you describe the core of your view?

As I said in my book Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, if I had to give a prize for the single best idea anybody ever had, I would give it to Darwin because evolution by natural selection ties everything together. It ties life and physics and cosmology; it ties time and causation and intentionality. All of these things get tied together when you understand how evolution works. And if you do not take evolution seriously and really get into the details, you end up with a factually impoverished perspective on consciousness, on the mind, on epistemology, on the nature of explanation, on physics. It is the great unifying idea.

I was lucky to realise this when I was a graduate student and I have been turning that crank ever since with gratifying results.

How does consciousness come about in a Darwinian universe?

First of all, you have to recognize that consciousness is not a single pearl of wonderfulness. It is a huge amalgam of different talents and powers which are differently shared among life forms. Trees are responsive to many types of information. Are they conscious? It is difficult to tell. What about bacteria, frogs, flies, bees? But the idea that there is just one thing where the light is on or that consciousness sunders the universe into two categories—that is just wrong. And evolution shows why it is wrong.

In the same way, there are lots of penumbral or edge cases of life. Motor proteins are not alive. Ribosomes are not alive. But life could not exist without them. Once you understand Darwinian gradualism and get away from Cartesian essentialism, then you can begin to see how the pieces fit together without absolutes. There is no absolute distinction between conscious things and non-conscious things, just as there is no absolute distinction between living things and non-living things. We have gradualism in both cases.

We just have to realise that the Cartesian dream of ‘Euclidifying’, as I have put it, all of science—making it all deductive and rational with necessary and sufficient conditions and bright lines everywhere—does not work for anything else apart from geometry.

Why are non-naturalistic accounts of consciousness—‘mysterian’ accounts as you call them—still so appealing?

I have been acquainted with the field for over half a century, but I am still often astonished by the depth of the passion with which people resist a naturalistic view of consciousness. They think it is sort of a moral issue—gosh, if we are just very, very fancy machines made out of machines made out of machines, then life has no meaning! That is a very ill-composed argument, but it scares people. People do not even want you to look at the idea. These essentially dualistic ideas have a sort of religious aura to them—it is the idea of a soul. [See the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on consciousness for an overview of the debate over the centuries.]

I love the headline of my interview with the late, great Italian philosopher of science and journalist Giulio Giorello: ‘Sì, abbiamo un’anima. Ma è fatta di tanti piccoli robot’ – ‘Yes, we have a soul, but it’s made of lots of tiny robots’ [this interview appeared in a 1997 edition of the Corriere della Sera]. And that’s it! If that makes you almost nauseated, then you have a mindset that resists sensible, scientific, naturalistic theories of consciousness.

Do you think that the naturalistic view of consciousness propounded by you and others has ‘won’ the war of ideas?

No, we have not won, but the tide is well turned, I think. But then we have these backlashes.

The one that is currently raging is over whether Giulio Tononi’s integrated information theory (IIT) of consciousness is pseudo-science [see the entry for IIT in the Internet Encylopedia of Philosophy for an overview]. I recently signed an open letter alongside a number of researchers, including a lot of the world’s very best on the neuroscience of consciousness, deploring the press’s treatment of IIT as a ‘leading’ theory of consciousness. We said IIT was pseudo-science. That caused a lot of dismay, but I was happy to sign the letter. The philosopher Felipe de Brigard, another signatory, has written a wonderful piece that explains the context of the whole debate. [See also the neuroscientist Anil Seth’s sympathetic view of IIT here.]

One of the interesting things to me, though, is that some scientists resist IIT for what I think are the wrong reasons. They say that it leads to panpsychism [‘the view that mentality is fundamental and ubiquitous in the natural world’ – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.] because it says that even machines can be a little bit conscious. But I say that machines can be a little bit conscious! That is not panpsychism, it is just saying that consciousness is not that magical pearl. Bacteria are conscious. Stones are not conscious, not even a little bit, so panpsychism is false. It is not even false, it is an empty slogan. But the idea that a very simple reactive thing could have one of the key ingredients of consciousness is not false. It is true.

It seems that antipathy towards naturalistic theories of consciousness is linked to antipathy towards Darwinism. What do you make of the spate of claims in recent years that Darwinism, or the modern evolutionary synthesis of which Darwinism is the core, is past its sell-by date?

This is a pendulum swing which has had many, many iterations since Darwin. I think everybody in biology realises that natural selection is key. But many people would like to be revolutionaries. They do not want to just add to the establishment. They want to make some bold stroke that overturns something that has been accepted.

I understand the desire to be the rebel, to be the pioneer who brings down the establishment. So, we have had wave after wave of people declaring one aspect of Darwinism or another to be overthrown, and, in fact, one aspect of Darwin after another has been replaced by better versions, but still with natural selection at their cores. Adaptationism still reigns.

Even famous biologists like Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin mounted their own ill-considered attack on mainstream Darwinism and pleased many Darwin dreaders in doing so. But that has all faded, and rightly so. More recently, we have had the rise of epigenetics, and the parts of epigenetics that make good sense and are well-attested have been readily adapted and accepted as extensions of familiar ideas in evolutionary theory. There is nothing revolutionary there.

The Darwinian skeleton is still there, unbroken. It just keeps getting new wrinkles added as they are discovered.

The claims that the evolutionary establishment needs to be overthrown remind me of—in fact, they are quite closely related to—the enduring hatred of some people for Richard Dawkins’s 1976 book ‘The Selfish Gene’.

Yes, some people do. But I think that it is one of the best books I have ever read and that it holds up very well. The chapter on memes is one of the most hated parts of it, but the idea of memes is gathering adherents now even if a lot of people do not want to use the word ‘meme’. The idea of cultural evolution as consisting of the natural selection of cultural items that have their own evolutionary fitness, independent of the fitness of their vectors or users—that has finally got a really good foothold, I think. And it is growing.

As one of the foremost champions of memetics as a field of study, you must be pleased that it is making a comeback, even if under a different name, given that earlier attempts to formalise it never really took off.

Well, the cutting edge of science is jagged and full of controversy—and full of big egos. There is a lot of pre-emptive misrepresentation and caricature. It takes a while for things to calm down and for people to take a deep breath and let the fog of war dispel. And then they can see that the idea was pretty good, after all.

You mentioned Stephen Jay Gould. In your memoir, Gould and several others get a ‘rogue’s gallery’ sort of chapter to themselves. How have the people you have disagreed with over the years influenced you?

Well, notice that some of my rogues are also some of the people that I have learned the most from, because they have been wrong in provocative ways, and it has been my attempts to show what is wrong with their views that have been my springboard in many cases. Take the philosopher Jerry Fodor, for example. As I once said, if I can see farther than others, it is because I have been jumping on Jerry like he is a human trampoline!

If Jerry had not made his mistakes as vividly as he did, I would not have learned as much. It is the same with John Searle. They both bit a lot of bullets. They are both wrong for very important reasons, but where would I be without them? I would have to invent them! But I do not need to worry about beating a dead horse or a straw man because they have boldly put forward their views with great vigour and, in some cases, even anger. I have tried to respond not with anger but with rebuttal and refutation, which is, in the end, more constructive.

And what about some of the friends you mention in the book? People like the scientist Douglas Hofstadter and the neuropsychologist Nicholas Humphrey?

People like Doug Hofstadter, Nick Humphrey, and Richard Dawkins—three of the smartest people alive! It has been my great privilege and honour to have had them as close friends and people that I can always count on to give me good, tough, serious reactions to whatever I do. I have learned a lot from all of them.

Nick Humphrey, for example, came to work with me in the mid-1980s and we have been really close friends ever since. I could not count the hours that we have spent debating and discussing our differences. If you look at the history of his work, you will see that he has adjusted his view again and again to get closer to mine, and I have adjusted my view to get closer to him. I accepted a lot of his points. That is how progress happens.

How do you differentiate between philosophy and science? In your afterword to the 1999 edition of Dawkins’s 1982 book ‘The Extended Phenotype’, for example, you say that that work is both scientific and philosophical. And in your own career, of course, you have mixed science and philosophy quite freely.

I think the dividing line is administrative at best. Philosophers who do not know any science have both hands tied behind their backs. They are ill-equipped because there is just too much counter-intuitive knowledge that we have gathered in science. That is one of the big differences between philosophy and science. In science, a counter-intuitive result is a wonderful thing. It is a gem, a treasure. If you get a counter-intuitive result and it holds up, you have made a major discovery.

In philosophy, if something is counter-intuitive, that counts against it, because too many philosophers think that what they are doing is exposing the counter-intuitivity of various views. They think that if something is counter-intuitive, it cannot be right. Well, hang on to your hats, because a lot of counter-intuitive things turn out to be true!

What you can imagine depends on what you know. If you do not know the science (or what passes as the science of the day because some of that will turn out to be wrong) your philosophy will be impoverished. It is the interaction between the bold and the utterly conservative and established scientific claims that produces progress. That is where the action is. Intuition is not a good guide here.

We all take for granted now that the earth goes around the sun. That was deeply counter-intuitive at one point. A geocentric universe and a flat world were intuitive once upon a time.

Darwinism, the idea that such complexity as living, conscious organisms can arise from blind forces, is counter-intuitive, too.

Yes. My favourite quote about Darwinism comes from one of his 19th-century critics who described it as a ‘strange inversion of reasoning’. Yes, it is a strange inversion of reasoning, but it is the best one ever.

It strikes me that some of the essential differences between your view and the views of others hark back in some way to Plato and Aristotle—the focus on pure reason and the immaterial and the absolute versus the focus on an empirical examination of the material world.

Yes, that is true. It is interesting that when I was an undergraduate, I paid much more attention to Plato than to Aristotle. Again, I think that was probably because I thought Plato was more interestingly wrong. It was easier to see what he was wrong about. Philosophers love to find flaws in other philosophers’ work!

That brings to mind another aspect of your memoir and your way of thinking more generally. You think in very physical, practical terms—thinking tools, intuition pumps, and so on. And you have a long history of farming and sailing and fixing things. How important has this aspect been to your thinking over the years?

It has been very important. Since I was a little boy, I have been a maker of things and a fixer of things. I have been a would-be inventor, a would-be designer or engineer. If I had not been raised in a family of humanists with a historian father and an English teacher mother, I would probably have become an engineer. And who knows? I might not have been a very good one. But I just love engineering. I always have. I love to make things and fix things and figure out how things work.

I think that some of the deepest scientific advances of the last 150 years have come from engineers—computers, understanding electricity, and, for that matter, steam engines and printing presses. A lot of the ideas about degrees of freedom and control theory—this is all engineering.

Since you mention degrees of freedom, whence free will? You are known as a compatibilist, so how do you understand free will in a naturalistic, Darwinian universe?

I think there is a short answer, which is that the people who think free will cannot exist in a causally deterministic world are confusing causation and control. These are two different things. The past does not control you. It causes you, but it does not control you. There is no feedback between you and the past. If you fire a gun, once the bullet leaves the muzzle, it is no longer in your control. Once your parents have launched you, you are no longer in their control.

Yes, many of your attitudes, habits, and dispositions are ones you owe to your upbringing and your genes but you are no longer under the control of them. You are a self-controller. There is all the difference in the world between a thing that is a self-controller and a thing that is not. A boulder rolling down a mountainside is caused deterministically to end up where it ends up, but it is not being controlled by anything, while a skier skiing down the slalom trail is also determined in where she ends up, but she is in control. That is a huge and obvious difference.

What we want is to be self-controllers. That is what free will is: the autonomy of self-control. If you can be a competent self-controller, you have all the free will that is worth wanting, and that is perfectly compatible with determinism. The distinction between things that are in control and things that are out of control never mentions determinism. In fact, deterministic worlds make control easier. If you have to worry about unpredictable quantum interference with your path, you have a bigger control problem.

I know that you have a long and ongoing dispute with, among others, the biologist and free will determinist Jerry Coyne on this.

Yes. I have done my best and spent hours trying to show Jerry the light!

Alongside Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, and Sam Harris, you were one of the ‘Four Horsemen of New Atheism’. In your memoir, you say that you were impelled to write your book on religion, ‘Breaking the Spell’, because you were worried about the influence of religious fundamentalism in America—and you say that your worries have been borne out today. In your view, then, we are seeing a resurgence of dangerous fundamentalism?

We are, yes, and we are seeing it across the world and across religions. I think that we have to recognise that a major part of the cause of this is the anxiety, not to say the terror, of the believers who see their world evaporating in front of their eyes. I warned about that in Breaking the Spell, and I said, ‘Look. We have to be calm. We have to be patient. We have to recognise that people are faced with a terrifying prospect, of their religious traditions evaporating, being abandoned by their children, being swept aside.’ No wonder that many of them are anxious, even to the point of violence.

In Breaking the Spell, I designed a little thought experiment to help those of us who are freethinkers, who are atheists, appreciate what that is like. Imagine if aliens came to America. Not to conquer us—imagine they were nice. They were just learning about us, teaching us about their ways. And then we found that our children were flocking to them and were abandoning musical instruments and poetry and abandoning football and baseball and basketball because these aliens had other pastimes that were more appealing to them. I deliberately chose secular aspects of our country for this experiment.

Imagine seeing all of these just evaporate. What?! No more football, no more baseball, no more country music, no more rock and roll?! Help, help! It is a terrifying prospect, a world without music—not if I can help it!

If you can sympathise with this, if you can feel the gut-wrenching anxiety that that would cause in you, then recognise that that is the way many religious people feel, and for good reason. And so we should respect the sorrow and the anger, the sense of loss, that they are going through. It is hard to grow up and shed religion. It has been our nursemaid for millennia. But we can do it. We can grow up.

Is there a need for another ‘New Atheist’ type of moment, then, given the resurgence of religious fundamentalism and violence in the world?

I am not sure that we need it. I am not going to give the New Atheists credit for this—though we played our role—but recent work has shown that the number of those with no religion at all has increased massively worldwide. Let’s just calm down and take a deep breath. Comfort those who need comforting. Try to forestall the more violent and radical responses to this and just help ease the world into a more benign kind of religion.

And religions are doing that, too. Many religions are recognising this comforting role and are downplaying dogma and creed and emphasising community and cooperation and brotherhood and sisterhood. Let’s encourage that. I sometimes find it amusing to tease Richard Dawkins and say to him, think about this evolutionarily: we do not so much want to extinguish religion as get it to evolve into something benign. And it can.

We need the communities of care, the places where people can go and find love and feel welcome. Don’t count on the state to do that. And don’t count on any institution that is not in some ways like good old-fashioned religion for that, either. The hard thing to figure out is how we can have that form of religion without the deliberate irrationality of most religious doctrine.

And that is a difference between you and Dawkins. In ‘Breaking the Spell’, you did not expend much energy on the arguments for and against the existence of a deity, whereas Dawkins in ‘The God Delusion’ (2006) was much more focused on that question.

Yes, but Richard and his foundation also played a major role in creating The Clergy Project, which I helped to found and which is designed to provide counsel and comfort and community for closeted atheist clergy. There are now thousands of clergy in that organisation and Richard and his foundation played a big role in setting it up. Without them, it would not have happened. So, Richard understands what I am saying about the need to provide help and comfort and the role of religion in doing so.

You mentioned music earlier, which you clearly love as you devoted a long chapter in your memoir to it. So, what for you is the meaning of life without God and without a Cartesian homunculus?

Well, life is flippin’ wonderful! Here we are talking to each other, you in England [Scotland, actually, but it didn’t seem the moment to quibble!] and me in the United States, and we are having a meaningful, constructive conversation about the deepest issues there are. And you are made of trillions—trillions!—of moving parts, and so am I, and we are getting to understand how those trillions of parts work. Poor Descartes could never have imagined a machine with a trillion moving parts. But we can, in some detail now, thanks to computers, thanks to microscopes, thanks to science, thanks to neuroscience and cognitive science and psychophysics and all the rest. We are understanding more and more every year about how all this wonderfulness works and about how it evolved and why it evolved. To me, that is awe-inspiring.

My theory of meaning is a bubble-up theory, not a trickle-down theory. We start with a meaningless universe with just matter, or just physics, if you like. And with just physics and time and chance (in the form of pseudo-randomness, at least), we get evolution and we get life and this amazingly wonderful blossoming happens, and it does not need to have been bestowed from on high by an even more super-duper thing. It is the super-duper thing. Life: it’s wonderful.

I completely agree. I have never understood the appeal of religion and mysticism and ‘spooky stuff’ when it comes to meaning and purpose and fulfillment, but there we are. In your memoir, you discuss the thinking tools you have picked up over the years. Which one would you most recommend?

It might be Rapoport’s rules. The game theorist Anatole Rapoport formulated the rules for how you should conduct any debate. These are the rules to follow if you want constructive disagreement. Each of them is important.

The first thing you should do is to try to state your opponent’s position so vividly and clearly and fairly that your opponent says they wish they had thought of putting it that way. Now, you may not be able to improve on your opponent, but you should strive for that. You should make it clear by showing, not saying, that you understand where your opponent is coming from.

Second, mention anything that you have learned from your opponent—anything you have been convinced of, something you had underestimated in their case.

Third, mention anything that you and your opponent agree on that a lot of people do not.

Only after you have done those three things should you say a word of criticism. If you follow these rules precisely, your opponent will know that you really understand him or her. You have shown that you are smart enough to have learned something from or agree about something with him or her.

What Rapoport’s rules do is counteract what might almost be called the philosopher’s blight: refutation by caricature. Reductio ad absurdum is one of our chief tools, but it encourages people to be unsympathetic nitpickers and to give arguably unfair readings of their opponents. That just starts pointless pissing contests. It should be avoided.

I know the answer to this question, but have you ever been unfairly read?

Oh yes! It is an occupational hazard. And the funny thing is that I have gone out of my way to prevent certain misunderstandings, but not far enough, it seems. I devoted a whole chapter of Consciousness Explained to discussing all the different real phenomena of consciousness. And then people say that I am saying that consciousness is not real! No, I say it is perfectly real. It just is not what you think it is. I get tired of saying it but a whole lot of otherwise very intelligent people continue to say, ‘Oh, no, no, no! He is saying that consciousness isn’t real!’

Well, given what they mean by consciousness—something magical—that is true. I am saying that there is no ‘real magic’. It is all conjuring tricks. I am saying that magic that is real is not magic. Consciousness is real, it is just not magic.

Do you have any future projects in the works?

I do have some ideas. I have a lot of writing about free will that has accumulated over the last decade or so and I am thinking of putting that together all in one package. But whether I publish it as a book or just put it online with introductions and unify it, I am not yet sure. But putting it online as a usable anthology in the public domain is a project I would like to do.

Further reading:

Darwinism, evolution, and memes

‘An animal is a description of ancient worlds’ – interview with Richard Dawkins, by Emma Park

Science, religion, and the ‘New Atheists’

Atheism, secularism, humanism, by A.C. Grayling

How three media revolutions transformed the history of atheism, by Nathan Alexander

Secular conservatives? If only…, by Jacques Berlinerblau

Can science threaten religious belief? by Stephen Law

Christopher Hitchens and the long afterlife of Thomas Paine, by Daniel James Sharp

Christopher Hitchens and the value of heterodoxy, by Matt Johnson

Meaning and morality without religion

What I believe – interview with Andrew Copson, by Emma Park

Morality without religion: the story of humanism, by Madeleine Goodall

‘The real beauty comes from contemplating the universe’ – interview on humanism with Sarah Bakewell

1 comment

Very nice interview.

The progress since Dennett and the other horsemen has been palpable in my lifetime. Thank you. Someone Daniel Sharp’s age may not appreciate atheists were considered a step below pedophiles not long ago. No more, at least in the West where the worry is more about pedophile clerics.

I do hope Prof. Dennet writes his book on free will. I just can’t get on board with his take, for example in his conversations with Sam Harris on the topic. I also agree with Annaka Harris that panpsychism makes a lot of sense.

Finally, Dennett’s thought experiment with aliens is not needed. The woke supply the hideous social situation that requires no imagining.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate