In the United States we are experiencing not a culture war, but something more like a culture Armageddon. I need not illustrate with too many examples. Just click on The New York Times’ homepage (about which more anon) to see where we are headed. What I will say is that it would be prudent not to judiciously give ‘both sides’ of this conflict between Left and Right; there is little merit in casting our national malaise as a standoff between two evenly matched, and equally reasonable (or unreasonable) belligerents.

This time-honoured – and under normal circumstances otherwise eminently reasonable – pose of ‘neutrality’ must be abandoned. This is because such an approach cannot account for the fact that American conservatism is convulsing and coming apart. A large swathe of its adherents are embracing the Alt-Right, White Christian Nationalism, Catholic Integralism and other overlapping species of authoritarian-friendly worldview. For such movements, violence, as we learned on 6th January 2021, is part of the playbook.

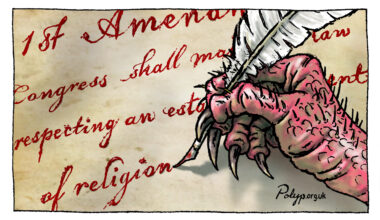

The freethinking community in the United States and beyond has a vested interest in paying very close attention to this development. For if there is one thing that adherents of all these worldviews dislike, rather passionately, it is ‘secularism’. No matter how the term is defined (see below), the S-word is correlated in these quarters with the Fall of Man, an affront to God, elitism, corruption, sin, contumely and rapine.

Which is why a recent opinion piece for the New York Times, ‘What Comes After the Religious Right?’, piqued my curiosity. Its author, a twenty-three year old hard-Right pundit affiliated with The National Review named Nate Hochman, forecasts the rise of ‘secular conservatives’ in the Republican Party. Growing numbers of Americans, he notes, are claiming no religious affiliation. A healthy share of these ‘Nones’, he contends, are attracted to current Republican policies. The ascent of these ‘barstool conservatives’, or ‘Middle American radicals’, as he refers to them, will lessen Christian Conservative power within the GOP, but ultimately broaden the right-wing electorate in the long run. All the better to check the ‘totalitarian’, ‘authoritarian’ ‘insanity’ of the Left.

Hochman thus adds his name to the long list of those who have predicted the imminent demise of the Christian Right. Whether he is correct about that is of less interest than his assertions about an ascendant conservative secularism. Having studied secular political systems for decades, I would argue that the claim is misleading and unpersuasive.

What is useful about Hochman’s argument is his willingness to decouple secularism from liberalism. It is essential to recall that distinct concepts like ‘secular’, ‘secularism’, ‘secularisation’ and ‘secularity’ are invoked in a bewildering variety of ways in public discourse. Hochman toggles between many of these definitions without any sense of the distinctions.

In colloquial American usage, a ‘secular’ person could be: 1) an atheist; 2) an agnostic; 3) neither atheist nor agnostic, but simply unchurched; 4) one who dislikes religion; but may be a believer in a higher power (scholars refer to this dislike as ‘anti-clericalism’); 5) a supporter of church/state separation; 6) a bearer of a materialist or this-worldly approach to day-to-day living, the likes of which were celebrated by George Jacob Holyoake; or 7) a proponent of using science, data and reason to address public policy concerns, or some combination thereof.

Then there is another term often taken as a synonym for secularism: ‘liberalism’. This is because John Locke, one of the architects of the idea of state neutrality vis-à-vis religion – a core concept of political secularism – is considered a founder of the liberal political project. The link has long persisted. In 19th-century America words like ‘secular’, ‘freethinker’ and ‘liberal’ were often used interchangeably. Thus, the National Liberal League in 1884 evolved into the American Secular Union.

Yet the long historical ties between secularism and liberalism do not rule out the possibility of secular conservatives. Who might be a secular conservative today in light of the definitions mentioned above? He or she might be a member of a non-Christian religious minority, such as Muslim, Jewish or Hindu Americans, who fear a Christian religious establishment. This person might be a Christian – imagine a Mormon or Catholic in South Carolina who is apprehensive about prayer sessions led by a Baptist teacher in her daughter’s public school. The person might be an atheist who prefers limited government.

A secular conservative could be an advocate of free markets and deregulation who also resents the state entangling itself with religion. Or he or she could be a national security hawk. The late senator John McCain comes to mind. He proclaimed himself a Baptist during his failed 2008 presidential run as a way of pandering to conservative Evangelical voters. Prior to that he was one of the few Republicans who dared publicly lambaste the Christian Right and bemoan its outsized influence in his party.

The common thread in all the secular conservative identities I have just mentioned is opposition to a government that imposes the theological precepts of one religious group or groups upon all other citizens. Hochman, however, has very different types of ‘secularists’ in mind. His examples are Tucker Carlson of Fox News, rightwing pundit Chris Rufo, Florida governor Ron DeSantis , and David Portnoy, founder of Barstool Sports (who in Hochman’s telling emerges as a principled champion of women’s reproductive freedoms).

How these polarising figures are ‘secular’, either in their own self-definition, or according to the many criteria that I and other social scientists have enumerated, is unclear. Hochman, I surmise, expects his ‘secular conservatives’ to advocate for a number of issues, including anti-immigration policies, relentless attacks on LGBTQ rights, opposition to critical race theory, fretting about ‘White Replacement’, and a loathing of ‘elites’ (by which is meant not the super wealthy who bankroll conservative media, but professors, scientists and journalists). But such issues do not preoccupy most people in America who call themselves secular.

‘Secular’ as they may be, Carlson, Rufo, DeSantis and Portnoy’s preoccupations do, however, resonate with white conservative Christians. Maybe that is why 81% of white Christian Evangelicals voted for Donald Trump in 2016 and 2020. (Hochman rather misleadingly cites data from GOP primaries, not the general election, to prove that secular, not religious, conservatives propelled Trump to victory.) The distinction Hochman draws between ‘secular’ conservatives and religious ones does not seem to result in significant policy disagreements between them, other than a slightly greater acceptance of gay marriage among the former.

So who are Hochman’s secular conservatives? Two that he does name, Portnoy of Barstool Sports and white nationalist Sam Francis, are not on record as having supported any of the possible meanings of secularism above. Hochman might have added figures like the philosopher Jordan Peterson. Had Hochman been more familiar with the freethought community perhaps he might have included those, like Bill Maher, Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins,* whose relations with American liberals and progressives have become increasingly strained. The vanguard of the New Atheists in the 2000s, they have engaged in their own sorts of denunciations of the Left and of progressive pieties. That some atheists have drifted into the Alt-Right has also been noted.

It is difficult to escape the conclusion that Hochman’s secular conservatives are overwhelmingly a multi-class cohort of aggrieved white guys. For the secularists named by Hochman, the single greatest challenge confronting the United States is not permitting lethal weapons to flow into the hands of mass murderers, but the teaching of critical race theory. The problem is not the pandemic of disinformation about ‘election integrity’, but gender-neutral bathrooms – or the very existence of transgender people. The problem is not white supremacy and insurrections that nearly topple our democracy, but ‘wokeness’ or ‘The Great Awokening’.

Hochman himself seems to recognise the mostly white cast of his secular conservatives as a potential imaging problem. In an attempt to diversify his coalition, the author tries to load black people and Latinos onto his secular conservative bandwagon. He writes: ‘it is likely that disaffected people of all races will continue to move into the Republican coalition.’ Yet the argument here is at once flimsy. It was misleading to imply, as Hochman does, that Trump gained an unusually high number of black votes: 88% of black people voted against him and a higher percentage of them voted for Nixon, Ford, and Reagan.

As for Latinos, the ones that do vote for the GOP are mostly traditionalist Catholics, Evangelicals and Pentacostals. In other words, they are not ‘secular conservatives’ at all. Rather, they are plain old religious conservatives who espouse standard anti-abortion and anti-LGBTQ views.

Which brings us back to the ‘Nones’. When Hochman points to the rise of the Nones (the non-Church affiliated) as an emerging GOP growth market, we must be sceptical. In the United States, Nones are overwhelmingly liberal, with 70-75% supporting classic liberal positions. Sociologists divide Nones into ‘atheists’, ‘agnostics’ and ‘nothing in particular’ (NIP). The largest group, the NIP, appear to be the least politically active among the Nones and most Republican friendly. Still, the NIPs show a very low likelihood of casting a vote for a candidate like Trump, and do not seem to be particularly aligned with the GOP.

Hochman, then, is not pointing to any looming secular conservative juggernaut that I can recognise. As far as I can tell, his ‘secular’ conservatives simply seem to be not overtly religious conservatives who have an affinity for the culture war policies of the Trump base and its elite mouthpieces at Fox News, National Review and beyond. Truth be told, Hochman does not appear to be describing classic conservatism either, but rather its take-no-prisoners, ‘make America great again’ variant. Whatever new conservative identity he sees on the horizon, it is one that has left behind a variety of well-known conservatives, including Bill Kristol, Steve Schmidt, Ana Navarro, Michael Steele, Nicole Wallace, and countless others.

The closest parallel I can see to Hochman’s secular conservatives are far-right wing parties like Rassemblement National in France. They have embraced French political secularism (laïcité), not out of love for its long tradition of Republicanism and disestablishment, but as a vehicle for anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim mobilisation. My point is that such figures have no real investment in secular principles; secularism is simply a means to an end.

I mentioned Holyoake earlier, and it is worth emphasising that the ‘Victorian Infidel’ made much of ‘sincerity’ as a defining feature of secular identity. As the ‘free speech’ debate intensifies and becomes increasingly complex in an age of social media, I want to suggest that both writers and the media that gives them a platform have an obligation to be sincere. I mention this because Hochman’s New York Times voice is different from the voice he uses when in dialogue with conservative colleagues.

Listening to Hochman’s many interviews, one gets a sense of the impending Armageddon I alluded to above. After the piece we are discussing, he did the rounds of conservative podcasts, telling one host, ‘The Left is (sic), “We are going to come for you and we are going to destroy your family and everything that you love and we’re going to run you out of the public square and we’re going to make it impossible for you to get a job if you don’t say men can become women”.’

A major problem we have with conservative media in the United States is that they do not say what they believe to be true. Fox News hosts famously downplayed the January 6th insurrection on air, while sending frantic messages to Donald Trump’s handlers to call off his hordes attacking the Capitol. In a word, they are insincere. Does free speech include the right to arguably mislead millions of people on a nightly basis?

Far from censoring Hochman, I am wondering if the Newspaper of Record had a responsibility to ask him to articulate, with sincerity, what the ‘secular’ conservative agenda entails. Is it White Replacement Theory as espoused by Carlson? Is it constant attacks on the rights of trans people? Is it a preemptive assault on ‘The Left’ in order to stave off its desire to ‘destroy your family and everything you love’?

So yes, there are secular conservatives. The nation’s small secular groups, overwhelmed by decades of Conservative Christian activism, would likely welcome them into their ranks. But nothing indicates they are poised to embrace the politics of Trumpian conservatism, its endless litany of grievances and its penchant for mass violence.

[* For Dawkins’ side of the story, see our interview with him – Ed.]

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate