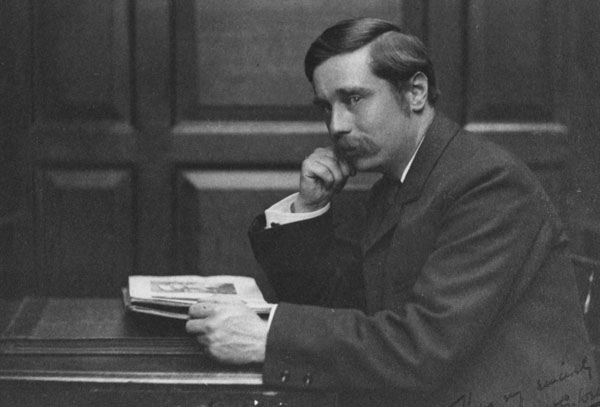

H G Wells died in 1946, almost eighty years ago. Yes, he was important in his time, but why care about him today? What could he possibly tell us about living in the twenty-first century?

As it happens, quite a lot. For one thing, he was a conservationist before David Attenborough was born. And what’s more, he saw where the fault lay. ‘Man,’ Wells wrote in his 1938 novel Apropos of Dolores, ‘is a biological catastrophe.’ Wells saw the dangers of, and warned his readers about, anthropogenic climate change in 1931. Change to the world ecology, he wrote in The Science of Life, ‘is becoming deliberate. What before was achieved by slow shiftings of balance due to unconscious competition is now being forced on nature at the point of human consciousness.’ Earlier even than that, before the First World War, Wells warned his readers:

Mankind used up material—insanely. They had got through three-quarters of all the coal in the planet, they had used up most of the oil, they had swept away their forests, and they were running short of tin and copper. Their wheat areas were getting weary and populous, and many of the big towns had so lowered the water level of their available hills that they suffered a drought every summer. (The World Set Free, 1914)

The quote for which Wells is best remembered notes what others took a century to work out. From The Outline of History (1920): ‘Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe.’ As he got older, Wells became more imbued with a sense of urgency that Homo sapiens needed to wake up to the dangers of their way of living. In a way now commonplace, Wells knew—in 1924—where the problem lay:

As soon as the mass urgency subsides we tend to relapse into our own little personal lives of eating, drinking, and ‘having a good time’, or ‘getting on’, of posing to ourselves and others, of thinking and talking ourselves into agreeable states of self-approval, of doing pleasantly spiteful things to people we dislike. (A Year of Prophesying)

Two generations before it became mainstream, H G Wells understood the impact humans were having on the climate and was under no illusions as to the challenge of surmounting the difficulties posed by that impact.

The key to understanding how Wells was so far ahead of his time is to grasp fully the influence of Arthur Schopenhauer. No thinker is mentioned more often by Wells than the great German pessimist. Neither is any philosopher mentioned as consistently throughout his career, beginning, middle, and end. It was the combination of his scientific education at the Royal College of Science, then run by T H Huxley, and his understanding of how people work, gleaned from life and via Schopenhauer, that gave Wells his unique perspective. To take one passage among several, here is Wells mid-career, in 1926:

Metaphysically I have never been able to get very far beyond Schopenhauer’s phrase: Die Welt als Will und Vorstellung [The World as Will and Representation, an 1818 book by Schopenhauer]. Life to me as to him, when he wrote that title at least, is a spectacle, a show, with a drive in it. (The World of William Clissold)

Wells’s grasp of Schopenhauer was broad and deep; he hadn’t just skimmed some slight anthology. He had read, judging from the various references and allusions to Schopenhauer, most of the philosopher’s work. This matters for two reasons. First, it provides some serious heft to what he said and ensured that he was without superficial confidence in human powers of reason or forbearance. Second, it is evidence against so many of the prejudices about what Wells said and believed—prejudices that have long since ossified into orthodoxy.

That the misconceptions have struck deep is evident. One prominent critic, A N Wilson, acknowledges that Wells wrote some good stuff early on, but then spent forty years writing stuff that isn’t worth reading (see Wilson’s 2005 book After the Victorians). This sort of view has enabled people to cherry-pick passages from an earlier work and jump to some negative conclusion, having not bothered to consult his later works, the ones Wilson declares not worth reading. As a result, we see all sorts of virtue-signalling denunciations of Wells as this or that. But, having read his later work, one sees how Wells changed his views on some matters and listened to new evidence. Implied in the phrase ‘following the science’ is the willingness to change one’s mind on receipt of new evidence. Wells understood this, even if many contemporary critics do not.

One of the more persistent modern prejudices about Wells is that he was a racist who supported eugenics. Here is the prime example of cherry-picking from an early source and ignoring all his later revisions and retractions. Wells supported positive eugenics—the idea favoured by Francis Galton of breeding from superior types to raise superior children—for about a year, around 1901. But when Wells, a confirmed Darwinian, read the work of William Bateson on Mendelian genetics in 1902, he came to appreciate the Lamarckian assumptions underlying positive eugenics and changed his mind. (Wells was also from far too lowly a place in the social hierarchy to be impressed for long by the idea of superior genes inevitably coming from privileged people.)

For twenty years or so after that, Wells supported an increasingly mediated version of negative eugenics—the idea of preventing those deemed unfit from breeding. Wells never supported resorting to the ‘lethal chambers’ that D H Lawrence and others waxed lyrical about, preferring education on birth control as the safest and most effective form of preventing unwanted births. By the end of the 1930s, Wells dismissed eugenics as ‘a mere speculation of the theorists’ (as he put it in The Rights of Man) unsupported by the science. Adam Rutherford’s recent work on the subject, Control: The Dark History and Troubling Present of Eugenics (2022), is positive about Wells’s record, noting that he was ‘a longstanding opponent of eugenics’.

When the Nazis took over, prominent among the books they burned were the works of H G Wells—and Wells was on their list of prominent people to be detained once their conquest of England was complete.

Wells’s views on race were more consistent. Unusually for his time, Wells was consistently anti-racist. Race hatreds, he wrote in The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1932), are the product of ignorance. ‘They are stupidities, they are vulgarities that the schoolmaster should anticipate and destroy.’ Later still, in ’42 to ’44: A Contemporary Memoir (1944), Wells attacked ‘claptrap phrases about backward races and inferior peoples.’

Wells has also been accused of all known strands of misogyny, particularly as regards his many affairs with women. But, as Andrea Lynn concluded in her lengthy study of Wells’s relationships, Shadow Lovers (2002), there were no victims. Wells was not predatory; the women he slept with had sought him out. In most cases, Wells and his lovers remained good friends after the affair ended. Wells was attractive to intelligent women and genuinely enjoyed their company.

Interestingly, Wells is among the first to bemoan the gender limitations of the English language, where the male pronoun has become the default option. He mentioned this first in 1905 and returned to it throughout his career. But it was his novel Ann Veronica (1909) that broke new ground. Wells’s protagonist unapologetically made her own choices: they weren’t always good decisions, but they were always hers, and unlike earlier ‘New Woman’ protagonists, her poor decisions did not necessarily lead to her demise. In her 1975 memoir The Tamarisk Tree, the feminist and socialist Dora Russell (wife of Bertrand) remembered Ann Veronica as a book that spoke to her generation.

Incredibly, one even sees Wells accused of being a proto-fascist. This was certainly not a view shared by the fascists themselves. When the Nazis took over, prominent among the books they burned were the works of H G Wells—and Wells was on their list of prominent people to be detained once their conquest of England was complete. The fascists were right to be angry. Wells had been a consistent critic of fascism and Nazism from the beginning, frequently vilifying both Hitler and Mussolini and viewing their ideologies as ‘gangster systems’ (see 1933’s The Shape of Things to Come). Wells’s 1927 novel Meanwhile has been described as the first anti-fascist novel ever written.1

Wells’s views on religion were also more nuanced than is usually supposed. The Freethinker has an honourable place in Wells’s development. In Experiment in Autobiography (1934), he recalls reading the magazine in Portsmouth in the 1880s; it helped him to escape the joyless and puritanical Anglicanism of his mother. Depending on what type of god one has in mind, Wells remained an atheist for the rest of his life.

He had a brief theistic wobble during the First World War, when he spoke of God the Invisible King (as the title of his 1917 book on theology had it). But even here, he specifically rejected the transcendental idea of God, trying to make something of the immanent notion of God, first spoken about by Kant, as a catch-all word to describe the finest emotions we have. Bishop John A T Robinson recycled the same sort of stuff in Honest to God in 1963 and was widely thought of as a heroic pioneer of a new vision of God. To his credit, Wells quickly backtracked on his foray into theology and returned to what he called ‘the sturdy atheism of my youthful days.’

And still the accusations flow. Regarding science, Wells always had a much more ambivalent attitude than his critics acknowledged. He was never the vapid apostle for science and technology that Aldous Huxley, C S Lewis, and others accused him of being. Wells valued science deeply but never made the mistake of supposing it to be an agency of salvation. Many of his stories featured scientists whose moral compass was in some way mangled. In The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind, Wells wrote: ‘Science casts a shadow wherever she distributes her benefits.’ Science is only as good as the people wielding it, in other words, and Wells consistently worried about the ape lurking just beneath the surface of Homo sapiens. Man, he wrote in What Are We to Do With Our Lives? (1931), ‘is an imperfect animal and never quite trustworthy in the dark.’

But didn’t Wells peddle over-confident dreams of utopias where science would save everyone and everything? When we look at Wells’s utopias, the mistake so often made is to confuse writing about a utopia with recommending it. And many of the books thought of as utopian are nothing of the sort; they are books warning the reader what may come if we aren’t very careful. They are better understood as histories of the future. It should never be forgotten that H G Wells is also rightly seen as a pioneer of the dystopian novel, most notably with The Sleeper Awakes (1910). It is hard to write Wells off as a utopian fantasist when he also led the way in writing dystopian visions of how things can go wrong.

Finally, a brief word should be said about Wells as a futurologist. Among the many things he foresaw was the internet. In 1938, Wells looked forward to the day when ‘any student, in any part of the world, will be able to sit with his projector in his own study at his or her convenience to examine any book, any document, in an exact replica.’ For decades he had been championing a world encyclopaedia in print form; this was to be updated very regularly. But the penny dropped in 1937 when he attended the World Congress of Documentation in Paris and learned about the new technology of microfilming.

A year later, Wells wrote a short work updating his idea for a world encyclopaedia, this time driven by technology. He called it the World Brain (also the book’s title). Wells also foresaw suburbia, working women as an everyday phenomenon, Alexa-style communication devices (he called them ‘babble machines’), flying as a normal means of transport, and warfare which could no longer distinguish between soldier and civilian. Not only did he predict the nuclear bomb just a year after Rutherford split the atom, but Wells even understood the terror potential of a dirty bomb.

H G Wells, then, served as a prescient Cassandra to our present predicaments. He advocated what we now call global governance (not to be confused with world government, which he especially condemned), where nations relinquish some sovereignty to share the resources of the Earth equitably and where people strive to educate themselves to overcome their natural proclivities for greed and short-term thinking. Over a half-century he produced some memorable works, both fiction and non-fiction, some of them ground-breaking. And all his books, ground-breaking or not, are enjoyable reading. As well as writing, he campaigned tirelessly for a better future or, as he got older, to warn people of the trash future that awaits us if we are not careful. We would do well to read him, even now. Especially now.

- This claim was made by, among others, the Soviet scholar Julius Kagarlitsky in 1966. Kagarlitsky’s son, incidentally, is now in prison for opposing the Russian invasion of Ukraine. ↩︎

Related reading

Humanists and ethical reform in mid-twentieth-century Britain, by Charlie Lynch

Bringing back the dialectic: interview with Stephen ‘Rationality Rules’ Woodford, by Samuel McKee

Ethical future? Science fiction and the tech billionaires, by Rahman Toone

‘Project 2025 is about accelerating the demise of a functioning democracy’: interview with US Representative Jared Huffman, by Daniel James Sharp

‘The real beauty comes from contemplating the universe’: humanism with Sarah Bakewell, by Emma Park

Morality without religion: the story of humanism, by Madeleine Goodall

What I believe: Interview with Andrew Copson, by Emma Park

Do we need God to defend civilisation? by Adam Wakeling

‘Nobody really understands what the consequences are’: Susie Alegre on how digital technology undermines free thought, by Emma Park

The end of the world as we know it? Review of Susie Alegre’s ‘Human Rights, Robot Wrongs: Being Human in the Age of AI’, by Ralph Leonard

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate